Amongst all the junior exploration companies out there,

Based in Vancouver, Tan Range was created in 1991 to explore for gold in Tanzania under the direction of its president, Marek Kreczmer, a geologist and engineer who continues to serve in that role to this day.

In 2000, following

But the real transforming event for Tan Range happened in February 2002, when the company agreed to merge with privately held Tanzania American International Development Corp. (Tanzam), a move that combined both companies’ grassroots gold properties in Tanzania’s Lake Victoria greenstone belt. Tan Range became the second-largest exploration-licence holder in Tanzania, after Barrick.

In taking over Tanzam, Tan Range issued 20 million shares valued at 35 per share, which boosted the number of outstanding shares to 70.8 million. At last count, the company had 80.2 million shares outstanding, for a market capitalization of $161 million, based on the recent $2 share price.

Created in 1998, Tanzam was owned by high-profile gold guru James Sinclair and his family (see sidebar, page B2). Tanzam brought to the merged company 51 prospecting licences in the belt, of which a dozen were already subject to joint-venture royalty agreements with Barrick.

The 51 licences were assembled through a $6-million exploration program comprised of prospecting, trenching and drilling. The work was highlighted by a $2-million, 36,300-line-km airborne magnetic and radiometric survey carried out over the entire Lake Victoria gold district by South Africa’s Geodass (since swallowed up by Fugro, based in the Netherlands) in 1999 and 2000.

Sinclair became Tan Range’s chairman and CEO, and, with his extensive market experience, he convinced the Tan Range board to remake the junior into a unique gold-investment vehicle structured around seeking out royalty agreements rather than the majority-minority interest partnerships typically struck between majors and juniors.

“Franco-Nevada Mining described the royalty game best by defining royalties as high-margin assets providing a direct interest in a mine’s cash flow, with exposure to new discoveries and production growth, yet without capital obligations or environmental liabilities,” Tan Range Chairman James Sinclair told shareholders at the company’s annual meeting in Toronto earlier this year.

“We simply can’t do better — I believe — than that. In our case, however, rather than buying them on the open market, we feel we can acquire royalties by exploring in target areas with world-class potential and world-class partners.”

Sinclair said there are three definitive criteria he has for making a transaction with a new partner: “give me some front money; show me you have more money to take it through the major, nearby expenses; and have requirements you have to meet, in terms of accomplishing a defined amount of exploration in metres.”

Indeed, Tan Range has come up with a general format for its royalty agreements:

— Tan Range invests no additional funds in exploring or developing the property and therefore has no further property risk after the agreement is signed;

— in years 1 and 2, the new partner must spend a certain amount of money on exploration and in years 3, 4 and 5, the partner must drill a specified number of metres. The partner then must complete a bankable feasibility study and make a production decision by the end of year 5.

— by the end of year 8, the partner must have put the project into production at a specified minimum rate or else face cash penalties. By then, the partner would have acquired a 100% interest in Tan Range’s interest in the licences, and Tan Range would retain a net smelter return royalty that ratchets up depending on the gold price.

— Tan Range has no environmental risk and no exposure to the type of suit that recently hit AngloGold and Gold Fields;

— The royalty is off balance sheet to the major producer, and Tan Range can, if it elects, take gold in payment rather than cash from the smelter. Thus it has no exposure to any derivative dealings the mine operator may undertake;

— the better the business climate is for Tan Range, the lower the operating expenses since the dealing of properties is its main business. When all its properties are dealt, Tan Range becomes a property management company — only with nothing to manage.

— going forward, new royalty agreements will include a provision whereby 1% of all royalties owed to Tan Range will be applied to social and development work in Tanzania.

“This business plan reduces our expenses as we grow, which is different from any other gold company I know,” stated Sinclair. “By negotiating contracts wherein the royalties rise with a rising gold price, we remain a true proxy for the gold price without the risk of ever-growing money demands, derivatives, labour, changing mining methods, and so on. I don’t think many have really understood how different we are yet.”

More to the point, the trading action seen from present-day royalty company

Since cash hasn’t started rolling in from any royalty payments, Tan Range has topped up it coffers over the past two years through the exercise of options and warrants and through a private placement, all overseen by the new Chief Financial Officer Victoria Luis (formerly CFO of Tanzam) and auditor PriceWaterhouseCoopers, which replaced KPMG in that role.

Between April and October 2002, a total of $3.6 million flowed in via the exercise of warrants and options, resulting in the issue of 6.3 million shares.

In February 2003, Sinclair agreed to buy between $1.5 million and $3 million worth of Tan Range shares in 24 monthly tranches, each valued at a minimum $62,500 and bought at the prevailing market price. By early September, he had spent $825,000 buying shares in seven tranches.

As of May 31, 2003, Tan Range had $2.5 million in cash and no debt except for $1.1 million in future income taxes owed. The company says its cash position, coupled with the Sinclair tranches, is sufficient to take it through 2004.

In another trailblazing move, the new Tan Range has vowed to issue no more significant quantities of options, rights or warrants.

Tan Range’s old warrants no longer exist and there is now less than 20% of the original insider stock options remaining, comprised of 1.8 million options exercisable between 40 and 96 and expiring between 2004 and 2007.

Instead, the company has launched a program whereby it will financially assist eligible employees, consultants and directors to buy Tan Range shares on the open market. For employees, the company will match contributions by 100% for up to 5% of salary and by 50% for 6-30% of salary; for consultants and directors, the matching contribution is capped at $10,000.

The new Tan Range has also stated that it has “no intention of putting into place any anti-takeover policy because we firmly believe they are designed solely to protect and entrench management at the expense of you the shareholder.”

Commented Sinclair: “We would not at any time interfere with the knowledge of, or participation in, a takeover. I’ve been involved in companies before where takeover bids have come in informally to the company and the shareholders haven’t been informed. I can assure you that’s not going to happen here — normally that’s done when the company is somewhat of a cash cow to management.”

Sinclair has also taken shareholder communications to a whole new level with the launch earlier this year of www.jsmineset.com. In this free online newsletter, he gives incisive daily commentary on the gold market and teaches retail investors how to use technical analysis as a trading tool. He has also used the site to prompt investors to take physical delivery of their gold shares, as he has done.

The site is managed by Tan Range’s communications point man David Duval, a mining journalist and former western editor of The Northern Miner.

Turning to Tan Range’s portfolio, the most-advanced property is Itetemia, situated immediately east and north of Barrick’s Bulyanhulu mine, about 55 km south of Lake Victoria.

In November 1999, Tan Range signed a non-royalty option agreement with Barrick at Itetemia, and the major has since spent in excess of $4 million on exploration. Barrick can acquire a 60% interest in Itetemia from Tan Range and a further 10% interest from Tanzania’s state mining company.

As part of the deal, Barrick subscribed for $4-million worth of Tan Range shares at substantial premiums to the going market price, but in order to vest its 60% stake, the major must still arrange project financing.

In 2001, drilling confirmed that the stratigraphy seen in Bulyanhulu’s two key reefs continues onto the Itetemia property, with one hole on the latter property returning a Bulyanhuluesque 2 metres grading 12.4 grams gold at a depth of 26 metres.

“There’s no stop sign on this (Bulyanhulu) reef at our borders,” said Sinclair. “I firmly believe that, because one of our concessions has 20,000 artisanal miners on it, and all of the major discoveries that are now operating over there have been made simply by following the locals — the artisanals have been there first. Buly had 200,000 artisanals on it in the early 1990s.”

The most-drilled mineralized body at Itetemia is the Golden Horseshoe Reef, which has been delineated from surface down to a depth of 440 metres.

Compared to the furious drilling Barrick carried at Bulyanhulu after its 1999 purchase, which boosted the resource from 3.6 million to 12 million oz. in under three years, Barrick has taken a slower pace at Itetemia. Still, the option agreement with Tan Range states that Barrick must put the property into production by 2005, so the major will need to decide on its next steps at Itetemia fairly soon.

The year 2002 ended with Barrick relinquishing eight joint-ventured Tan Range properties but agreeing to retain 11 others, including Itetemia.

Sinclair hinted that the Itetemia agreement was under re-negotiation, and added that it’s “not really an uphill negotiation to change your percentage to a royalty.”

Early this year, Tan Range struck a set of royalty agreements with Montreal-based

Northern Mining can acquire 100% of Tan Range’s underlying interests in the licences by paying US$70,000 in cash upfront, US$1.6 million in option payments, and US$1.5 million in property expenditures over five years.

The new partner must also complete a feasibility study and make a production decision before 2009, and achieve production within 18 months or be subject to cash penalties.

Tan Range will retain a net smelter return royalty that ranges from 0.5% at a gold price of US$250 per oz. to a maximum of 2% at US$380 per oz.

The licences cover 696 sq. km adjacent to Northern Mining’s 30%-owned Tulawaka gold project, where Barrick holds the remaining 70% and serves as operator — a result of its takeover of Pangea. A feasibility study is now underway on Tulawaka’s East zone, where resources total 1.7 million tonnes grading 14.19 grams gold per tonne.

“Northern Mining is a nice company, but nothing much to get crazy about,” commented Sinclair. “However, they certainly proved to us they have the money and they have the technical capacity to meet their requirements.”

Northern Mining is now headed up by CEO Carlos Bertoni, the former vice-president of exploration at Golden Star Resources.

Australia’s Resolute Mining, which opened the Golden Pride gold mine in Tanzania in 1998, recently lent Northern Mining US$5.5-million in the form of a convertible debenture due by year end. If the debenture is converted, Resolute would receive 7.8 million shares, equivalent to an 18.6% stake in the junior.

In July, Tan Range closed nine royalty agreements with

The Ghanaian gold miner can acquire 100% of Tan Range’s interest in the licences by paying US$100,000 in the first year and US$930,000 over five years. The major must also spend US$800,000 on exploration in the first two years, and carry out 6,000, 8,000 and 10,000 metres of drilling in years three, four and five, respectively.

Ashanti must complete a bankable feasibility study and make a positive production decision before the end of the fifth year to keep in good standing. Later, Ashanti must be producing at a rate of 50,000 oz. gold per year or face penalties.

Tan Range retains an NSR with terms similar to the ones struck in the Northern Mining agreement.

Ashanti’s flagship asset in Tanzania remains its 545,000-oz.-per-year Geita open-pit gold mine, which is equally owned with

Tan Range now has 78 prospecting licences in the Lake Victoria greenstone belt, of which a 28 are subject to royalty agreements.

“I’m not sure if there’s been another company of our nature that has as many concessions dealt, but that’s way below what my goals are,” said Sinclair. “We want to put our emphasis in the field, because I want to see those deals go up — that’s my measure of how things are happening, and it should be the shareholders’ measure, too.

“From a business sense, we are right where we want to be. The values now in the Tanzanian greenstone belt are being recognized by other developments within the belt.”

Tan Range is also exploring properties on its own, and three in particular have displayed some enticing high-grade gold in grab samples, trenches and shallow drilling.

“Luhala, Lunguya and Kigosi are less advanced but nonetheless hold significant promise in that they are located in geological environments that are reminiscent of the world’s largest gold-producing camps,” said Kreczmer. “These properties have been explored to our own account, but we have reached a point that we feel our objectives would be better served by taking on a partner.

— Luhala — This 130-sq.-km property is situated 70 km south of Mwanza. Now wholly owned by Tan Range,

One hole drilled by Tan Range a year later through a contact between tightly folded rhyolite and iron formation units returned 14.4 metres of 5.7 grams gold at a depth of 30 metres. Encouragingly, two marker horizons related to this contact can be traced for 12 km.

Tan Range describes the mineralization as being analogous to the style seen at the Lupin and Musselwhite gold mines in Canada.

Tan Range has since become more interested in the fold noses at Luhala, which provide wider mineralized areas and are believed to be highly fractured, and so may have provided greater surface area for gold deposition (and thus higher gold grades).

Complicating matters is the fact that the soil cover over fold noses in Tanzania is typically much thicker owing to the increased weathering of the highly fractured rock.

Tan Range is considering a diamond drilling program at Luhala comprised of 20-30 holes totalling 3,000 metres.

— Lunguya — Situated 15 km south of Bulyanhulu, Lunguya hosts gold mineralization within, and parallel to, a contact between mafic volcanics and granites that has produced a very strong geochemical anomaly over 12 km in length.

Some 43% of grab samples taken last year by Tan Range from artisanal miners’ workings and other areas graded above 5 grams gold.

The company followed up with shallow reverse-circulation drilling that confirmed the presence of two gold-bearing quartz veins, about 20 metres apart, that range in thickness from 1-3 metres and extend at least 350 metres in length.

Further diamond drilling in 2003 didn’t produce spectacular results but it did confirm the RC work and extended the lengths of the two veins to 480 metres.

Tan Range can earn an 80% interest in Lunguya by making certain staged expenditures and bringing it into production.

q Kigosi — Last October, the Tanzanian government awarded Tan Range the 650-sq.-km Kigosi property, situated in the southwestern portion of the belt. There, Tan Range has identified three high-grade gold-bearing veins, two of which occur at the north end of a 3.5-km northwest-trending shear structure that transects a greenstone/felsic-intrusive contact at a very shallow angle.

Tanzam’s airborne geophysical survey also generated 195 magnetic anomalies that are perhaps related to kimberlite deposits. Tanzam sampled half of them for kimberlite indicator minerals, and seven contained the indicator mineral ilmenite and displayed surface textures indicating a nearby source.

“We haven’t put an emphasis on our diamonds targets,” Sinclair told shareholders in February. “As a company, we don’t want to be in the diamond business because the diamond business is dehumanizing and it requires very special knowledge and significant financing.

“Of course, the diamond business in Canada is entirely different, but in Africa… you’ve seen all the embarrassments that’ve come out of the tanzanite fields [in Tanzania]…that’s the wild west — they spend more time killing each other and having wars out there. It’s just not something we as a company would want to be involved in.”

Still, he added that Tan Range has protected its diamond interests in its agreements “in case our partners happen to stumble over them while they’re out there.”

By June, however, Tan Range had identified a strongly magnetic, circular anomaly, 1.5 km in diameter, that the company considers to be the top priority among 33 anomalies identified to date on Tan Range licences.

This prompted Kreczmer to state that Tan Range is “looking forward to broadening the scope of our exploration activities into diamonds…”

The only industrial-scale commercial diamond mine in Tanzania is

Though it’s a small junior, Tan Range is helped in its exploration efforts by a technical advisory committee, created last year, that includes James Oliver, a former senior geologist with Teck, and Jan Klein, former chief geophysicist at Cominco.

“The greenstone belts in Tanzania are unique as a depository of large gold deposits, and the fact is they’ve been relatively unexplored compared to other parts of the world,” said Sinclair.

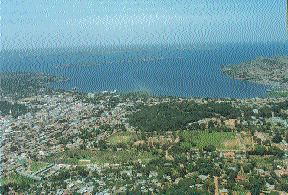

In the past decade, some 36 million oz. have been discovered in the Lake Victoria greenstone belt, and Tanzania now ranks as Africa’s third-biggest gold producing nation, after South Africa and Ghana.

For Sinclair’s views on the gold market, please see related article in the main section of The Northern Miner.

Be the first to comment on "Tan Range’s royalty structure unique among explorers"