Near Kangiqsujuaq, Que. — For several years, the magic word in base metals exploration has been “nickel,” and a large number of junior exploration companies have tied their fortunes to it. Many have looked for a niche in developing relatively small deposits where concentrate could be sold to a major nickel producer. But

Canadian Royalties, which was the first junior into the Cape Smith belt when nickel prices began to rise three years ago, has also been by far the most successful in finding new mineralization and new resources. It has outlined a new deposit at Mesamax, southeast of Raglan and east of the Expo-Ungava deposit, discovered by Amax in the 1960s but now held by Canadian Royalties. And it has checked off a string of prospects, some now drilled, that bolster its belief that the sequence of mafic and ultramafic sills south of the Raglan deposit is also a nickel camp like Raglan’s northern sequence.

Mesamax, the company’s very own discovery, is estimated to have a resource of 1.8 million tonnes at average grades of 1.9% nickel, 2.2% copper and 0.08% cobalt, plus 0.9 gram platinum, 4.3 grams palladium and 0.3 gram gold per tonne. That estimate, put together in June by Strathcona Mineral Services, takes in two mineralized bodies — a lower massive-sulphide zone of 760,000 tonnes with average grades of 3.4% nickel and 4.1% copper, and an upper zone of disseminated and net-textured sulphides, with about 1.1 million tonnes running at roughly a quarter of the grade of the massive mineralization.

“Amax drilled and came very close,” says veteran geologist Bruce Durham, the company’s president. The deposit’s geophysical signature is quite subtle: it is a weak conductor that shows up on a single line of an airborne electromagnetic survey, along with coincident single-line magnetic high.

On the ground, it stays subtle: frost-heaved boulders are the only sign of mineralization. The deposit is buried by overburden, but it is not a true “blind” discovery; the mineralization does come to the bedrock surface. There, it forms an oxidized upper zone, probably around 150,000 tonnes, that Strathcona excluded from its resource calculation, pending more information about its metallurgical characteristics (and also because there was no reliable information about its density).

That the upper oxidized zone is still in place after the last ice age suggests to Durham that the area was only weakly glaciated.

Over at Expo-Ungava, the company is finding out that, as often happens, everything that was known yesterday is wrong.

There is a resource estimate on Expo-Ungava, dating back to 1960s drilling by Amax. It amounted to 15.5 million tonnes grading 0.6% nickel and 0.8% copper, but Amax did not get assays for platinum group metals, and the company is placing little reliance on the old estimate, which greatly predates National Instrument 43-101. Much material was included that would probably not make an economic cutoff, and Canadian Royalties’ examination of the old core suggests that a single resource was calculated even though there are two distinct styles of mineralization in adjacent bodies — true massive sulphides overlain by net-textured sulphide-silicate rock.

Project manager Todd Keast told The Northern Miner he would expect a smaller tonnage but a higher grade out of any new resource estimate. He also pointed to a third style of mineralization, remobilized or metasomatic copper-palladium veinlets and disseminations, which would not contribute much to the tonnage but show very high palladium grades.

The Expo-Ungava body is proving to have a more complex shape than had originally been thought, with positive implications for the size of the resource. The typical mineralized zone had been thought to have a relatively simple bowl-like shape, occupying topographic lows in the gently folded ultramafic sills that host it. Below that, unmineralized sediments underlie the sills, and had been thought to represent the end of the mineralization.

Intensive drilling

More intensive drilling is indicating that the contact between the sediments and the sills is a series of interlayered tongue-like structures. That suggests that some earlier holes may have been stopped in a tongue of sediments that could be underlain by more ultramafic rock, which might also be mineralized.

That was confirmed by a recent hole in Expo’s Northeast zone, EX04-71, which intersected an ultramafic body below the previously known “bottom” of the host sill — a 24.6-metre intersection that graded 1.23% nickel, 1.03% copper and 0.06% cobalt, with 0.3 gram platinum, 1.4 grams palladium and 0.04 gram gold per tonne.

Three holes drilled 425 metres to the west of EX04-71 intersected multiple zones of disseminated and massive sulphides, with grades typically between 0.5 and 1% nickel, and roughly the same amount of copper. More massive material graded up to 3.56% nickel and 0.5% copper over a 1-metre core length, or 2.17% nickel and 1.52% copper over 1.2 metres. One of the holes ran through a total of 50.1 metres of mineralization, which averaged out to 0.44% nickel, 0.55% copper and 0.03% cobalt, with 0.2 gram platinum, 0.8 gram palladium, and 0.07 gram gold per tonne.

Three other holes about 275 metres west of EX04-71 encountered wide zones of massive and disseminated sulphides as well, including a 43.5-metre length that graded 0.39% nickel, 0.6% copper and 0.03% cobalt, with 0.15 gram platinum, 1 gram palladium and 0.1 gram gold per tonne.

Closer again to EX-04-71, a fan of three holes drilled from a collar 60 metres to the west intersected thick disseminated and massive mineralization. An 80.8-metre intersection ran 0.65% nickel and 0.67% copper, with cobalt and precious-metal credits, including 11 metres of more massive mineralization with 2.6% nickel and 2.86% copper, where palladium grades rose to 5.6 grams per tonne.

Recent infill drilling to the southwest, on the original Expo deposit, has intersected mineralization with grades comparable to the known resource, also over core lengths of 30-90 metres. A more reliable resource estimate, based on the infill drilling and including the new Northeast zone (first drilled last year), should be available by the end of the year.

South trend

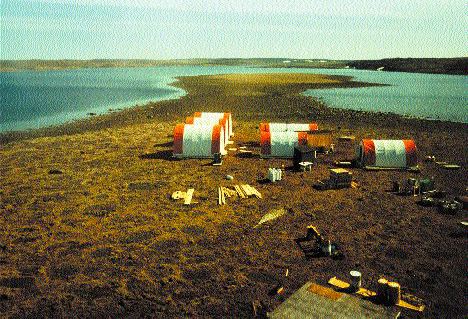

Even though you can see the lights on Raglan’s old Donaldson shaft from Canadian Royalties’ camp, the company doesn’t think of its project as a potential satellite operation for Raglan. Its target, instead, is to build up enough resources to justify a mine and mill, while taking advantage of the infrastructure that has come to the area over long years of development at Raglan. That means finding resources along the South trend comparable to the ones Falconbridge has on the North trend. Canadian Royalties’ grassroots exploration program has evolved from the basic fly-it-and-drill-it philosophy the company started with.

The most obvious magnetic and electromagnetic anomalies in the area were the first to be drilled, but it’s the more subtle ones, like Mesamax, that proved to be mineralized. In 1999, the company was looking for sill-like bodies with strong magnetic signatures; now it looks for single, isolated magnetic highs in the right stratigraphic horizons, with relatively weak conductors. (Many of the stronger electromagnetic conductors found in the earliest airborne surveys turned out to be graphitic layers in the sediments.) Targets can be narrow, and a survey flown on 100-metre spacings can completely miss a deposit.

Two that didn’t get away were Lac Mequillon and Tootoo. Showings at Mequillon have been known since the late 1950s; subsequent field work, and Canadian Royalties’ drill holes in 2002 and 2003, have picked up mineralization along a 1.4-km strike length.

Geologically, it is a Mesamax lookalike, with mainly disseminated nickel-copper mineralization in pyroxenite-peridotite sills. “You have to do a lot of work with the

hand lens,” says project manager Keast.

Tootoo — like Mequillon, about 15 km southwest of Expo — is a higher-grade massive body hosted by a 5-km-long pyroxenite sill. Its structure is poorly known and there is little outcrop in the area, so there is no model that can be confidently applied to predict just where the ultramafic sills are. The geologists believe there were at least two deformation events in the Tootoo area, and one product of that was a highly variable topography at the base of the sills where the sulphides are concentrated. An electromagnetic conductor can be shallow on one survey line but deep on the next one.

But as Canadian Royalties gets steadily more discriminating about its exploration targets, the success rate has gone up. And in an underexplored belt like this, there will always be plenty to drill.

Be the first to comment on "Canadian Royalties unravels the pattern in Ungava"