Vancouver — Peru’s mineral potential is as attractive as ever, but newly imposed royalties and recent mine-site protests have created an undercurrent of political risk that appears to be softening the pace of investment in the mining sector.

Foreign companies are still busy finding and developing mines, but environmental and non-governmental organizations (NGOs), as well as local citizens, are equally busy making their concerns known to as wide an audience as possible. One major gold mine was blockaded last fall, protests have erupted at several other mine sites, and local opposition has forced at least one company to drop plans to build a mine.

The cautious mood among foreign mining companies was evident last year when the government sought to auction off Las Bambas, a copper skarn deposit in the southern department of Apurimac. The deposit was described as “having the potential to become another Antamina,” a major copper-zinc mine that began production in 2001. Proven reserves were reported as being 40.5 million tonnes grading more than 2% copper, while “potential reserves” stood at about 500 million tonnes of more than 1% copper.

At least 14 companies pre-qualified for the auction, but many of them (mostly majors) dropped out after the government imposed new royalties on mining projects.

Peruvian business leaders opposed the push for a royalty of between 1% and 3% (depending on sales), pointing out that mining accounted for about 60% of the nation’s exports, or about US$7 billion in sales, last year alone. But leftist politicians won the day, and the new laws were approved last summer.

A few months later, the government awarded the concession for state-owned Las Bambas to London-listed

Not long after Xstrata’s bid was accepted,

The agreement, signed last month, allows Japan’s Sumitomo group to acquire an equity position of between 21% and 25% in the Peruvian company that owns and operates Cerro Verde. It also allows Peruvian-based

Under the terms of the newly signed agreement, Sumitomo, Buenaventura and other shareholders will provide US$440 million as partial financing for the US$850-million expansion. The rest will come from project debt.

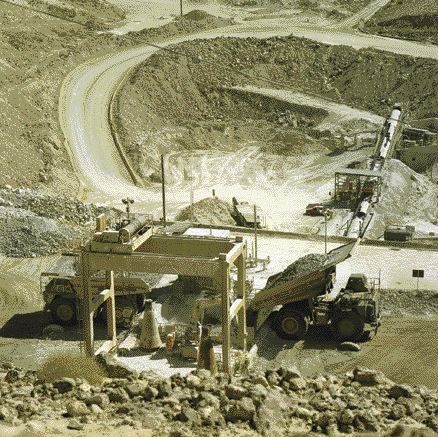

Cerro Verde currently consists of two open pits, Cerro Verde and Santa Rosa, and a solvent extraction-electrowinning (SX-EW) plant for production of cathode copper. Annual copper production stands at 100,000 short tons.

The expansion is focused on a primary, sulphide deposit beneath the oxide orebody now being mined. A new concentrator will be built to process the sulphide resource of 1 billion tons averaging 0.51% copper.

Mining is expected to begin in late 2006, with full production forecast for the first half of 2007. By that time, the expanded mine complex is expected to be producing 300,000 short tons copper per year.

Some analysts speculated Phelps Dodge took on partners to minimize political risk, though there’s no hint of that in the company’s descriptions of the project. Chairman Steven Whisler describes the expansion of Cerro Verde as “one of the building blocks of the company’s future” and says the sulphide deposit offers “attractive economic returns because of its low stripping ratio.”

The expansion is expected to create 2,400 construction jobs at peak construction, and 350 permanent jobs at the mine, which already employs 660. It is also expected to generate economic benefits to Peru, particularly to communities near the mine site.

Many Peruvians have growing concerns about the environmental and socio-economic impact of mining, partly because of nationalist sentiment but also because the risks associated with mining appear to outweigh the potential rewards. Even state politicians concede that previous administrations have failed to deliver basic services to poor regions where many rich mines are located.

Last fall, local residents blocked the road to the Yanacocha gold mine operated by

The protest came as a surprise, as Yanacocha had operated for more than a decade and even become South America’s largest mine, with annual production of 3 million oz. Newmont was preparing to develop the nearby Cerro Quilish deposit, which hosts 3.7 million oz. gold, when citizens became concerned it might pollute local water supplies. NGOs became involved too, as water is a scarce and valuable commodity in drought-plagued Peru.

The blockade lasted two weeks. To diffuse the volatile situation, Newmont asked the government to revoke its licence to develop the deposit. The company then began meeting more frequently with concerned local residents.

Peru’s new government is also taking steps to ensure that more economic benefits from mining flow to the regions where mines are situated. The new royalty laws are expected to help correct some of these past injustices. Mining companies are also paying more attention to community plans and projects that will benefit local communities.

Tambogrande

While it is likely Newmont will eventually resolve matters at Cerro Quilish, there is little hope the Tambogrande massive sulphide deposit in northern Peru will be developed anytime soon.

And yet opportunities are abundant.

Antares’ goal is to develop an open-pit copper mine using SX-EW technology. The company can acquire the project by paying US$15 million in stages over five years.

If the project advances to the feasibility stage, Antares will have to pay US1 for every pound of copper included in the resource in excess of 2.2 billion lbs.

— The author is a former editor of The Northern Miner and currently works as a freelance writer and filmmaker based in Vancouver.

Be the first to comment on "Reward outweighs risk in Peru’s mining sector"