Perth, Western Australia — In mid-February, nickel miner

The rise came from a better production quarter and the release of some high-grade nickel hits on a targeted mine extension.

Australia is in a commodities boom where nickel is a key player — in sulphide terms purely out of Western Australia. The zest for nickel is not just because the commodity is in good shape but because a series of junior companies and the odd mid-tier company are giving great performances, and investors are loving it.

Mincor is not only an example but a pace-setter of the change that took place at the turn of the new millennium. No longer is the market totally dominated by

There was the rocky start to pioneering lateritic nickel-cobalt production that saw one of the 3-billion-dollar developments basically disappear.

WMC had a poor industrial accord and industrial relations discord in the past at its Kambalda operations, where it launched sulphide nickel production in Australia at the beginning of the 1970s. However, it created a win-win situation in 2000 at its maturing and cost-inefficient operations that had become unloved in the Melbourne head office.

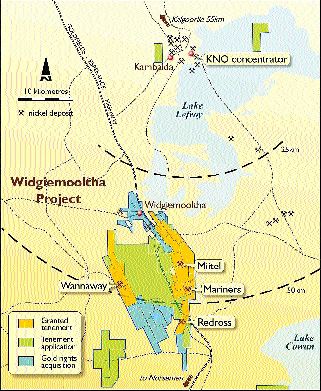

WMC sold the Miitel, Redross, Wannaway and other targets out on the Widgiemooltha Dome to Mincor, which had come through as a then-Iscor-group-supported junior company headed by David Moore.

Miitel was a ready-made target that allowed Moore to get the junior into rapid production, originally as a joint venture with the parties that it bought out in 2004.

The WMC deal involved Mincor mining and then delivering ore to WMC’s Kambalda concentrator — on WMC’s side providing new feed to then be channelled through the South Kalgoorlie smelter and/or to the coastal refinery at Kwinana.

Mincor became a role model, for other Kambalda region mines that WMC had mothballed were sold to juniors — again providing the win-win scenario where the junior just mined and delivered ore to WMC.

Mincor’s operations manager, Jim Reeves, one of those who had worked at WMC’s Kambalda operations, said Mincor was cranking up production as fast as it could. The Miitel mine is at 20,000 tonnes per month, and production was moving into the North Miitel zone, where high-grade hits indicate the tenor of ore grade could increase. Wannaway, in the southern leases, is running down and into remnant mining at between 3,000 and 5,000 tonnes per month, but Reeve pointed out that this operation began with reserves of 290,000 tonnes, and 430,000 tonnes have been mined to date.

The Redross mine is ramping up to 15,000 tonnes per month by mid-year while Mariners is being opened up to 18,000 tonnes per month.

Mincor’s half-year profit for the December half was up 143% to an after-tax A$10.12 million, with Miitel the performer by providing 131,231 tonnes at 3.07% nickel to Kambalda.

In the heart of Kambalda is the Long shaft, purchased by

Heading Independence is geologist Chris Bonwick, who worked on Long in his formative days, and running the mine is Tim Moran, who spent several years as WMC’s resident manager at Kambalda.

Bonwick says the success in finding new shoots and ore positions has been aided by the Fluxgate TEM sensor system, which has proved ideal in the saline environment.

“There’s so many opportunities out there for nickel,” Bonwick said. “It’s like the 1980s (Australian) gold boom.”

WMC put Australia on the nickel map at the start of the 1970s and is still the biggest player in the business and, in fact, in a large part of the 1980s and 1990s, was often the sole sulphide nickel operator. The only other durable operation is the Yabulu lateritic nickel-cobalt refinery, near Townsville in Queensland, now owned by

WMC still leads the pack in terms of mining, as well as dominating processing, and in 2004 produced a total of 276,033 tonnes of nickel metal. It has Leinster and the big disseminated sulphide mine at Mount Keith, and gains a healthy ore feed from all the juniors now mining its old operations around Kambalda. WMC, in the news these days through the unsolicited takeover bid by

Moving rapidly into second place is the Canadian-headquartered

It is also mining the Silver Swan project, acquired with the takeover of MPI Mines, whose executives moved out with precious metals assets, including its Stawell gold mine in Victoria.

Importantly, it secured the Bulong lateritic nickel refinery and facilities in the fire sale from this disastrous venture and is putting its controlled Activox process through its paces, with successful testing at its Tati nickel mine in Botswana.

Laterites in Western Australia were a new-wave exercise in the 1990s that proved a big bad dumper for most of the early participants. Surviving today are the Cawse operation, under the

There was a big learning arc for these operations, and one of the observant students sitting on the wall was BHP.

Research group Intierra’s Minmet service lists more than 100 deposits as having resources or are moving into blueprint, and this includes companies that have put a new lease of life into Western Australian operations, including the famous Windarra mine that put a big spark into the 1970s boom for the then Poseidon Ltd. Poseidon in its corporate travels almost capsized a few times but travelled well into Robert de Crespigny’s Normandy Mining group that was absorbed three years ago by

Junior

One interesting player is David Burt, who seven years ago was given the Industry Award at the Australian Nickel Conference by this writer for what must be the most impressive discovery work in Australia’s relatively short nickel history. Burt led the teams that found Nepean, Mount Keith and Silver Swan and is now managing director of

Another interesting player is

ConsMin’s Michael Kiernan transformed the company in

to a successful manganese and chromite miner in the Pilbara region and has, in the past two years, been undertaking “basement” investments for nickel and iron ore, including a shareholding in

The low-profile presence of Canada’s

Like many of the greenfields nickel explorers, one of the concepts they are using in remote areas of Southern Australia’s Gawler Craton and Western Australia’s northeastern goldfields is the Voisey’s Bay model.

This is shown at the Barton nickel prospect in the western sector of Southern Australia’s Eyre Peninsula, where Inco can earn 60% from

Overlooked by many is the recent financial performance of

— The author is a contributor to Australia’s Paydirt magazine.

Be the first to comment on "Australia’s nickel boom"