SITE VISIT

Anchorage, Alaska — In the early days of exploration at a property near the small town of Delta Junction in Interior Alaska, a bunch of geologists who’d had a few too many beers began jumping up and down. They may have been jumping for joy, imagining a rich gold vein beneath their feet, or more likely, they were jumping to keep warm, as this region is one of the coldest on the planet in winter. Someone nicknamed the strange dance the Pogo dance, and the name stuck. Today in the same spot, the Pogo mine is producing its first gold bars in a joint venture between Canadian mining major Teck Cominco (TEK.SV.B-T, TCKBF-O) and Japan’s Sumitomo.

A recent Alaska Miners Association tour of Pogo coincided with the beginning of operations. Having waited a long time and endured a 3-hour early morning bus ride from Fairbanks, Alaska, to see the mine, the geologists in the group were keen to spend as much time underground as possible. About another three hours, as it turned out.

“To a geologist, it’s like a cathedral down there,” one said on his reluctant return to the surface. “A cathedral of quartz.”

On the other hand, the sparkling dots in the quartz could be gold or they could be pyrite; the miner who drove us down there wasn’t too sure. The largest visible gold here is the size of a match head, according to Jack DiMarchi, Teck-Pogo’s chief geologist. The drift-and-fill method of mining is being used here; the drifts, 15-sq.-ft. horizontal tunnels that lead off the main decline. At the end of each of the two shifts per day, blasting takes place. To blast one block of about 250 tons of ore, 60 holes have to be drilled. This is considerably less ore than in other methods of mining such as long-hole stoping, which progress more quickly.

Complex geology

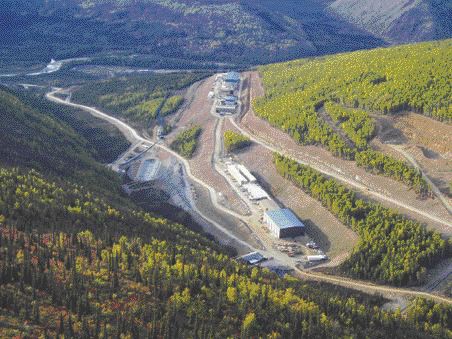

Pogo is a geologically complex deposit in which three different potentially economic veins have been identified. The ore zone at Pogo covers an area that measures 3,500 by 2,000 ft., with an average vertical thickness of 12 ft., although in places it is up to 30 ft. thick. A total of 13,000 ft. of underground development is already in place at the mine, with three portals, at 1,525, 1,690 and 1,875 ft. above sea level.

The L1 vein and the smaller L2 vein, 450 ft. below it, are going to be mined, while the L3 vein, 350 ft. below the L2 vein, requires further exploration. The pressure of having to send ore to the mill has focused geologists’ minds at Pogo.

“We’re past the time where we have the benefit to kind of scratch our head over these problems and take a week to figure them out,” DiMarchi said during a presentation at the Arctic International Mining Symposium in Fairbanks.

The veins are hosted within shallow-dipping shear zones that began life as thrust faults. In between the three main quartz veins, there are many parallel smaller veins. Problems arise when miners run into small-scale faults. These faults can’t be detected ahead of time, DiMarchi explained, so they weren’t built into the model and are having a significant impact on production. Sometimes it isn’t even clear in which direction the drilling should go. The aim is to find a control point farther along, somewhere the geologists know their model is correct. Ultimately, these challenges cause higher dilution (contamination of ore with barren wall rock) and higher costs.

Permitting and construction caused a hiatus in exploration outside the known deposit, but for 2006, Pogo has an exploration budget of $2.7 million; 35,000 ft. of helicopter-supported drilling is planned, as well as geophysical surveys.

Processing

An 11-ft. diameter conveyor tube that will bring ore from the mine to the mill wasn’t yet in operation, so ore was being trucked to the mill instead. As in most metals mines, ore is first crushed and ground to a 50-micron average size in a huge semi-autogenous grinding (SAG) and ball mills. It then goes through a gravity circuit and flotation cells that produce a 10% concentrate, meaning that the concentrate is 10% of the weight of the ore. The concentrate is reground and run through a cyanide leach circuit, with a carbon-in-pulp (CIP) process to pull the gold out of the solution.

All that remains on the production side is then for the gold to be made into a sludge that is melted in the furnace and then poured to form a gold bar. But that still leaves the much larger volume of tailings to be dealt with. And in Pogo’s case, the tailings pose specific challenges. Two giant Larox filters that emit periodic high-pitched roars like wounded dinosaurs squeeze the water out of the tailings to produce a filter cake containing only 15% moisture.

Teck Cominco and Sumitomo recently announced that the target production rate of 2,500 tonnes per day will not be achieved at Pogo until early 2007, instead of summer 2006 as originally planned. Instead, Pogo will be operating at about 60% of that rate while it awaits delivery of a third filter, due in December.

“The capacity of the filter plant is inadequate,” said Teck Cominco president and CEO, Don Lindsay, in a late-April conference call. “It is believed that the capacity has been compromised by finer-than-expected tailings and the presence of clay in the ore.”

The third filter will cost $10-$12 million, the company said.

The filtered tailings at Pogo go to the dry-stack tailings facility on a windy slope by a mountainside. Dry-stack tailings allow Pogo to avoid having to maintain and monitor a tailings pond for years or decades after closure. A dam creates a speed bump to catch water that comes down from the valley, and a diversion ditch above the tailings facility enables the mine to divert as much water around the property as possible, in accordance with Environmental Protection Agency requirements. The mine’s permits call for zero discharge of water.

— The author is a freelance writer based in Anchorage, Alaska.

Be the first to comment on "Pogo: Alaska’s ‘cathedral of quartz’"