At least two people are dead following protests at Anvil Mining’s (AVM-T, AVLMF-O, AVM-A) Kulu copper mine in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC).

On April 25, Anvil issued a release stating that two of its employees were killed when a group of protesting artisanal miners burned down a guesthouse owned by the company just outside of Kolwezi, in the southeastern province of Katanga.

A cook, employed by Anvil, and a contracted security guard, are the victims.

Sources in the DRC say protesters became incensed when an artisanal miner was allegedly killed while being removed from Anvil’s property. The dead man is said to be 30-year-old Kayembe Mukoj.

The company has confirmed two deaths related to the April 24 incident, while African news agencies say another two are dead, with the possibility of a fifth.

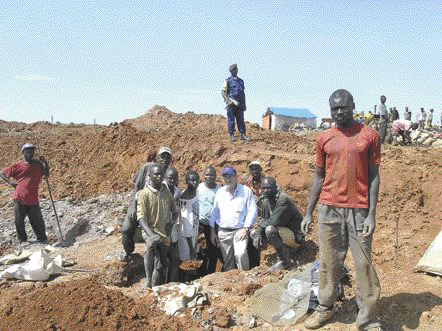

While Anvil would not comment on Mukoj’s death, the company says it has been trying to remove illegal artisanal miners from its land for months. Anvil says it has no problem with legal artisanal miners — those that pay a government fee for a permit.

The exact cause of Mukoj’s death is still a subject of debate. A non-governmental organization (NGO) in the Congo, the League against Corruption and Fraud (LICOF), reports the man drowned in a river while fleeing. But the news agency AFP reports that an eyewitness claims to have seen an Anvil security guard throw the man down a well. The South African-based security company contracted out by Anvil denies the charge.

Patricia Feeney, head of Rights and Accountability in Development (RAID) — an NGO active in the region — says news of the dead artisanal miner raised the ire of many Kolwezi residents. When a group of locals was denied a meeting with the mayor to discuss the situation, fuel was added to the fire.

Anvil says the protesters numbered over 500, and disputes reports that as many as 1,000 people participated.

“It started with a very few people,” Anvil spokesman Robert LaVallire says of the protest. “But they added people as they walked through the town.”

Sources say protesters were eventually dispersed when local police fired live ammunition into the crowd, killing as many as two people. Thus far, government officials have confirmed only one death.

Since Anvil’s association with the 2004 Kilwa incident — in which the Congolese military, using Anvil trucks and aircraft, killed some 100 villagers — the company has committed itself to strict transparency procedures when incidents arise.

In compliance with its own policy, the company quickly notified the UN mission in the Congo, MONUC, as well as the DRC government.

Staff members of the governor of Katanga’s office flew into Kolwezi the day after the incident to address the situation. The company is awaiting the outcome of their investigation.

Anvil shut down operations as a precautionary measure, and moved two of its employees 250 km away from the site.

But on May 2, the company said the mine had been reopened and was operating at full capacity.

In its release, Anvil said it is “extremely upset that these deaths have occurred and is making every effort to assist the affected families and to protect its staff.”

Anvil continues to work with Pact, a Washington, D.C.-based NGO, to help establish its social programs in Katanga. The company says it will invest close to US$1 million in social programs this year, with 10% of net earnings going to the community. LaVallire says that number would likely rise as the price of copper rises.

In Toronto, Anvil’s shares fell just 3% following the news. At presstime, they were trading at $8.40.

Be the first to comment on "Bloodshed in the Congo"