The following is an excerpt from a report entitled Minerals and Africa’s Development, released by the United Nations’ Economic Commission for Africa and the African Union. For the full report visit africaminingvision.org.

As late as the beginning of the nineteenth century, despite the many years of direct contact with European traders and the influx of European goods, most African societies still produced their own iron and its products, or obtained them from neighbouring communities through local trade. The quality of iron products was such that, despite competition from European imports, local iron production survived into the early twentieth century in some parts of the continent. This was the case at Yatenga in modern-day Burkina Faso, where in 1904 there were as many as 1,500 smelting furnaces in production. The production process covered prospecting, mining, smelting and forging. Different types of ore were available all over the continent and were extracted by shallow or alluvial mining. A variety of skills were required for building furnaces, producing charcoal, smelting and forging iron into goods. Iron production was generally not an enclave activity but a process that fulfilled the totality of socio-economic needs. It also fitted the gender division of labour within communities.

Copper production and use have a longer genealogy than iron in some parts of Africa. From ancient Egypt through parts of modern Niger, Mauritania and Central and Southern Africa, African societies have been mining and using copper and its alloys for centuries. Today’s major copper producing areas in Africa, notably the Copperbelt, were sites of indigenous production for many years before the takeover by colonial foreign mining companies. According to Paul Tiyambe Zeleza, a professor of African studies, “there have hardly been any copper-producing areas in the twentieth century in Africa that were not worked before.” In most places, copper was produced through open-cast as well as underground mining.

In addition to utilitarian objects such as wires, rods, vessels and other utensils, copper smiths produced jewellery, ornaments and cast art pieces such as statues.

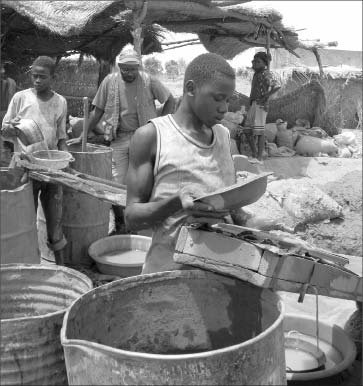

The patterns of indigenous artisanal and small-scale mining exhibited in pre-colonial copper mining are not unlike those in the gold-mining industry – which also had a long history – in Northeastern, West and Southern Africa. In the millennia preceding colonialism, West and Southern Africa were major exporters of gold to the rest of the world. More than 4,000 ancient gold workings have been found in Southern Africa alone. Production by foreign companies during the colonial era in many cases initially used generations of indigenous knowledge about the location of the precious metal and appropriate local mining sites. While prospecting methods varied among societies, gold mining involved panning of alluvial deposits, as well as surface or underground mining. Across Africa, modern artisanal gold mining retains strong continuities with pre-colonial practices.

Despite the allure and status of gold, salts were the most important commodities in parts of pre-colonial Africa. Trade in salts was the most important regional commercial activity in several areas, including the Sahel and the Sahara, especially the Western Sahara, central Sudan, the northern section of the western Rift Valley and its plateau borderlands, and the Great Lakes area around the modern border of the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Uganda.

Salts were extracted from a range of sources with different processes. The most important sources in the Sahel and the Sahara were rock salt deposits, mined from pits and saline ponds, on the top or edges of which salt crusts accumulated, owing to high rates of evaporation. Several thousand tons of these salts – sodium chloride, sodium sulphate, sodium carbonate, potassium chloride, calcium carbonate, sodium phosphate, potassium sulphate and calcium sulphate, in various combinations and concentrations – were each produced and gave rise to a far-flung export trade that served diverse consumption and industrial purposes. This trade reached as far as present-day Benin, Ghana, the Niger, Nigeria, Togo and parts of Burkina Faso and Mali, and as far south of the Congo River basin.

The colonial creation of export mining

The competition to find and control sources of raw materials, including minerals, was one of the main drivers of European penetration and eventual colonial partition of Africa in the last quarter of the nineteenth century. Between 1870 and the Great Depression of 1929, the pre-colonial patterns of production and consumption of minerals – where these activities were firmly located and integrated in the local economy – were radically altered and replaced by a colonially induced pattern, in which foreign-owned mining enclaves dominated most colonial African economies.

The British, Belgian and Portuguese colonies were prominent in the emergence of Africa’s colonial mining industry, reflecting their generous resource endowments and colonial mining policies – and for Britain, its leading place in the global economy. German ambitions were thwarted with its defeat in the First World War. The considerable mineral resources of its southwest Africa colony (now modern Namibia) became available to British and South African capital, but German financiers were active in the South African mining industry. Although French investors were important players in southern African mining before the First World War, French colonial mining policy and activity picked up late, from the thirties.

These mineral-based opportunities attracted heavy European migration to the colonies where most policies discriminated in favour of the new immigrants over Africans, both in terms of access to mineral rights and employment in the mining industry. Africans were usually relegated to low-skilled, low-wage and dangerous work. Initially, the development of the colonial mining economy centred on high-value minerals such as gold and diamonds.

This changed, however, as the processes of industrial and technological advancement in the world’s dominant economies led to demand for hitherto unused or underexploited minerals, and to the discovery of new uses for known minerals. Between 1870 and 1939 technological advances and industrial development boosted demand for copper, and worldwide copper production grew twentyfold. By the thirties the central African Copperbelt colonies of northern Rhodesia and the Belgian Congo were among the top copper exporters. Cobalt was an important associated mineral and the copper belt, mainly the Belgian Congo, quickly became its biggest source.

Manganese was discovered in the Gold Coast (modern Ghana) in 1914, and under the pressure of wartime requirements and the cessation of Russian exports the colony rapidly became a major exporter to the U.K. and its allies, principally the U.S. By this time European gold mining had finally taken off in the colony after the false starts of the late nineteenth century.

From 1909 British firms took over tin mining in Nigeria’s Jos Plateau, and the country’s production became crucial during the Second World War, after the Japanese expulsion of British forces from Malaya.

From the 1870s Africa, starting with South Africa and subsequently the Congo, the Gold Coast and Sierra Leone, came to dominate world diamond production, a position strengthened from the thirties by growth in the industrial use of diamonds. This changed the centuries-old situation where only gem diamonds had value, and gave great importance to the industrial diamond production in the Belgian Congo and the Gold Coast.

By the turn of the twentieth century South Africa had emerged as a major producer of diamonds and gold, and its considerable and diverse mineral wealth became globally important. By 1910 minerals accounted for more than 80% of South Africa’s exports, and more than 40% of those from no

rthern and southern Rhodesia, the Gold Coast and the Belgian Congo, and a significant part of those from Angola, Sierra Leone and Southwest Africa.

Most of the private foreign capital invested in Africa from 1870 to 1935 went into mining, and much colonial public investment was intended for developing mining. South Africa received the bulk of the investment and the subsequent reinvestment of the considerable profits from its diamond and gold mines, fuelling the expansion – and transformation – of the wider economy, as well as the country’s emergence as a racially segregated country and the dominant economy in Southern Africa, with the other economies in its orbit.

Be the first to comment on "Mining history: African mining on the eve of the colonial period"