VANCOUVER — Glencore Xstrata (LSE: GLEN) will appoint a woman to its board by year-end, a move that will end its stance as the only British blue-chip company with an all-male board.

The mining and commodities trading major has been feeling pressure to respond to a 2011 government report that noted a lack of diversity within the management ranks of Britain’s biggest companies.

However, the mining sector has not likely exerted much of that pressure. The reason: miners are trying, and it simply takes time.

That sentiment was evident at the annual Canadian Institute of Mining, Metallurgy and Petroleum (CIM) convention that recently wrapped up in Vancouver. The conference’s theme was “Mining 4 Everyone,” and the concept sparked much discussion around mining’s inclusivity and image. Conversations ranged from female participation to native involvement and foreign versus local mine management.

Within that range, the discussions had a common thread: miners believe diversity is beneficial for mining on many levels, but despite years of effort, it will take more time for demographics and patterns to reach a satisfactory state.

CBC journalist Mark Kelley moderated the conference’s plenary session and started by listing off statistics about women in mining: females hold only 7% of the directorships of the 500 largest mining companies in the world, which is the lowest representation of any sector, including oil and gas; those top-500 miners only have seven female CEOs; there is only one female CEO among the world’s 100 largest mining companies; and fewer than 10% of those employed in mining are female.

“I would humbly say to you that in many ways, you have an image problem,” Kelley said.

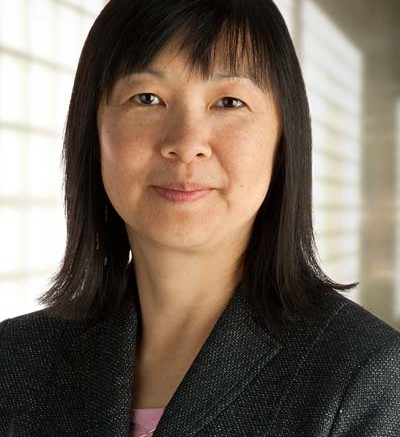

It’s a problem that has persisted despite attention. Alice Wong, chief corporate officer with Cameco (TSX: CCO; NYSE: CCJ), has worked 27 years for the uranium miner.

“I look across this audience and I think, ‘Well, it’s better than it was 27 years ago — I see more female faces,” Wong said. “And that’s good, because diversity makes each company and the industry better. I know we’ve spent a lot of time and effort over the last 25 years as a company trying to develop diversity in our workforce. Diversity doesn’t happen by accident.”

The panelists agreed that corporate programs and targets are part of the solution. Wong believes that targets drove Cameco’s increasing diversity, which has positioned the company as the largest aboriginal employer in Canada.

The other two female panelists, Kaminak Gold’s (TSXV: KAM; US-OTC: KMKGF) president and CEO Eira Thomas and Rio Tinto’s (NYSE: RIO; LSE: RIO) regional vice-president in Canada Virginia Flood, were less enthusiastic about affirmative action.

“I’m not really a big proponent of targets per se,” Flood said. “What’s really important is that you have the job because you merit it.”

Thomas agreed and went further, pointing out this illuminates the reason for a shortage of women in mining.

“We have to ask: Is there a barrier to women participating to a greater degree in the industry and, if so, what is it?” she said. “Is it the attitude of senior management? Or is it that there aren’t enough women with the right qualifications? [Wong] used the example of being singled out back in her physics class — that’s where it begins. It begins with education and it begins with children, and encouraging kids to make non-traditional choices.

“We need to make sure women who are qualified are getting placed, but we also have to work on getting more women into the qualified category.”

Of course, low female involvement is only one aspect of mining’s image issue. As the panelists discussed, the mining sector is also seen as dirty, greedy and insensitive towards local needs and benefits.

“I think we give ourselves an image that mining is only about extraction and engineering,” Flood said. “When mining makes it into the public domain, it’s usually due to a tragic event. Many don’t connect improving living standards to mining.”

Whether image and reality align is partly a matter of perspective — some people believe exploration and mining are inherently bad for the environment and for people living in the affected area, no matter how many jobs are created.

The relationship between miners and Canada’s aboriginal communities is a perfect example. Many Canadians — native and non-native alike — believe mining hurts these communities by damaging traditional lands and disrupting traditional behaviours such as hunting and fishing. But mining also employs more aboriginal Canadians than any other sector and generates millions of dollars in business opportunities for local residents.

Thomas now heads Kaminak Gold, but before that she was deeply involved in discovering and developing Canada’s northern diamond fields.

“There has been $60 billion mined in the north since 1993,” Thomas said. “For the Northwest Territories the big diamond discoveries heralded a large change for aboriginal engagement. Three diamond mines now create huge value and benefits, such as 19,000 person-years of employment. And 50% of those are aboriginal workers.”

The indirect benefits are also significant.

“There has been almost $4 billion spent with aboriginal businesses from the diamond sector,” Thomas said. “There are literally hundreds of aboriginal businesses that resulted from the development of our diamond industry.”

Like female involvement, however, there are foundational gaps that limit aboriginal involvement in mining.

“Northern Saskatchewan as a population has 40,000 people in 40 communities,” Wong said. “Eight of out ten people are of aboriginal heritage and 60% have no grade 12.”

Cameco has pulled from that population for its entry-level jobs, but Wong says more is required to increase aboriginal involvement on other levels.

“What do we need to do now? We need to move them into professional jobs, into technical jobs, into management,” she said. “That’s our challenge and that’s where we’ve ben focusing of late: on scholarships, education, early skills identification, training in the community, and for those already in our workforce, we have put into place supported training.”

As for Glencore Xstrata’s diversity initiative, its decision to soon appoint a female to its board follows the British government’s 2011 Davies Review, which found a lack of diversity among the management teams of Britain’s biggest firms. The report suggested a target: that all companies on the FTSE 100 — the index of the 100 largest public companies on the London Stock Exchange by market capitalization — aim to have women in a quarter of their board seats by 2015.

The pressure has worked. When the report came out in 2011, women held 12.5% of the FTSE 100’s board seats. By March 2014 that stake had climbed to 20.7%.

Miners were not the quickest to respond, but in March Chilean miner Antofagasta appointed Vivianne Blanlot as a director, leaving Glencore Xstrata as the only FTSE 100 company without female representation on its board.

Soon that will change, and every FTSE 100 company will have

at least one female director. And that is a start.

Be the first to comment on "Mining’s slow march towards workforce diversity"