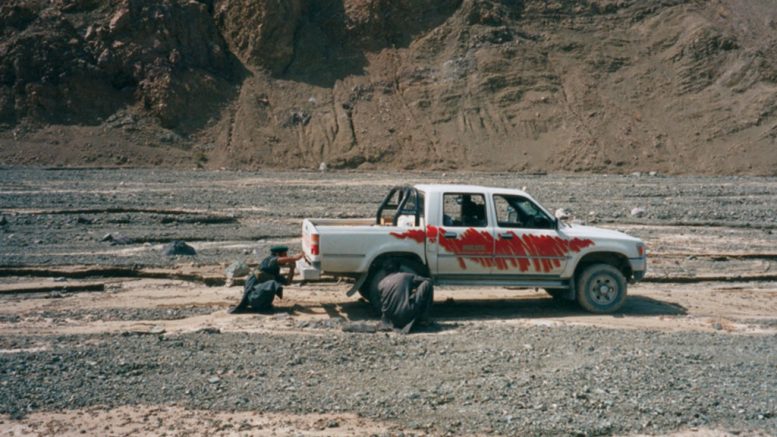

Western Pakistan is a fascinating place. It’s remote, arid, tribal, and these days, a Taliban stronghold — not the friendliest of spots for westerners planning on coming home still attached to their heads. It was slightly safer when I was there in 1997, although it still had its moments.

As a government-sanctioned traveller carrying out mining-related business, I was allowed to go pretty much anywhere off-road, as long as I took two guards — known as “Levies men” — with me at all times.

My job was prospecting for copper deposits hot on the heels of BHP’s massive Reko Diq discovery in the Chagai Hills (pronounced “cha-ee”).

But the Balochistan desert was an iffy place once you got off the road. It was infested with what I was told were drug convoys carrying opiates, coming through at night, heading from Afghanistan to the Makran Coast of Iran on the Gulf of Oman. There, the contraband would be loaded onto speed boats heading to Dubai, and transhipped to the end users in Europe.

Groups of 20 to 30 vehicles, heavily protected by anti-aircraft guns mounted on pickup trucks, would drive through Pakistan as fast as possible, across the salt pans and reg desert, not stopping for anyone. “shoot first, and disappear” was said to be their modus operandi.

As for me, I had noticed the ubiquitous tire tracks all heading in the same north–south direction.

One fine day, off the road north of Dalbandin (a hellish dustbowl town, loosely described as a “city”) heading to the Chagai Hills, my Balochi geologist and guide, Naseem, politely told me we had to go and pay our respects to the local headman connected to the infamous drug convoys.

As long as he knew we were working in the area, we’d be left alone, and, hopefully, not shot at by crazed smugglers packing 50-calibre guns.

Seemed like a reasonable trade-off to me, and besides, Naseem said he knew the man, so it would be quick.

We pulled up to a square mud-brick compound with a small metal door.

Naseem knocked, and a small slot opened at eye level. In a pure Indiana Jones moment, a pair of intense dark eyes peered suspiciously out at us.

Muttering something in Balochi, Naseem handed a business card through the slot, and it clanged shut.

We waited.

After half an hour in the blazing sun, the door opened and a flurry of locals came out, jumped into their trucks, and left in a cloud of dust.

We were ushered into a large, carpeted room, with big cushions on the floor, but otherwise devoid of furniture. A low, round table sat in the middle of the room, heavy with local food: grilled, curried and fried goat, lamb, roti, eggs, onion and lentil daal, hard white cheese, and rose water to drink.

It was quite the spread, and obviously meant for us. Sure enough, we were beckoned over by a large man carrying a machine gun and invited to help ourselves. He was one of four guards stationed around the room with an impressive “don’t-even-think-about-it” look to them. I didn’t.

There was a knock on the door and our host, whom I’ll call “Ahmed,” came in and warmly greeted Naseem. They obviously knew each other well.

My turn next, and after the usual extended courtesies, we sat back down with Ahmed to eat lunch. Naseem filled him in on where we wanted to go, what we were doing, and that was it.

We were apparently safe to get on with our work.

Except for the slightly worrying moment when Ahmed invited me to visit Afghanistan with him. His family owned a small copper mine and he politely asked if it would be of interest to our company.

I could see the dollar signs blinking behind his eyes. Everyone there knew about BHP’s giant Reko Diq project, so Western mining companies were obviously going to pay top dollar for copper wherever it was.

My lame response about not having an Afghan visa, so I’d better not, was met with derisory laughter from Ahmed and the guards: I wouldn’t need a visa if I went with Ahmed, because his brother was the governor of whatever Afghan province the mine was in.

This was rapidly becoming a bit of a squeaky bum moment, and starting to look like an invitation I couldn’t refuse. (A vivid image of me, five years hence, chained to a tree in a small Afghan village with my friend the goat popped into my brain, prompting more than a few beads of sweat.)

Thankfully, Naseem, thinking quickly, bailed me out using all the local courtesies he could muster: Oh, very sorry, we’d love to, but … gosh, is that the time? We really must be going — we couldn’t possibly do it because our schedule is tight, and besides, what would the Levies men think, eh? Don’t want them getting ticked off at us now, do we? After all, they had guns and they were with me to make sure I didn’t do anything daft (like head off to Helmand with a warlord), and would get into pots of trouble with their commander back in Dalbandin if I got kidnapped and fed to the camel spiders.

We ate up and left, much to my relief.

A few months later I was supping a pint in my home base of Budapest, chatting to a well-connected friend who worked for a Western Embassy. I told him the story and showed him Ahmed’s business card (yes, warlords carry business cards).

His eyes opened wide with recognition and my friend let out a soft whistle. He told me Ahmed was one of the leading smugglers of opiates into Europe. Ruthless, rich, powerful, nigh on untouchable, and well connected. And I’d turned down an invitation from him. Which in my mind, is a close as I’ll ever come to being a bad ass.

— Ralph Rushton is an exploration geologist who prospected the Tethyan belt from Bulgaria, through Turkey and Iran, and into Western Pakistan in the mid-1990s.

Be the first to comment on "Odds ‘n’ Sods: Dodging drug smugglers in Western Pakistan"