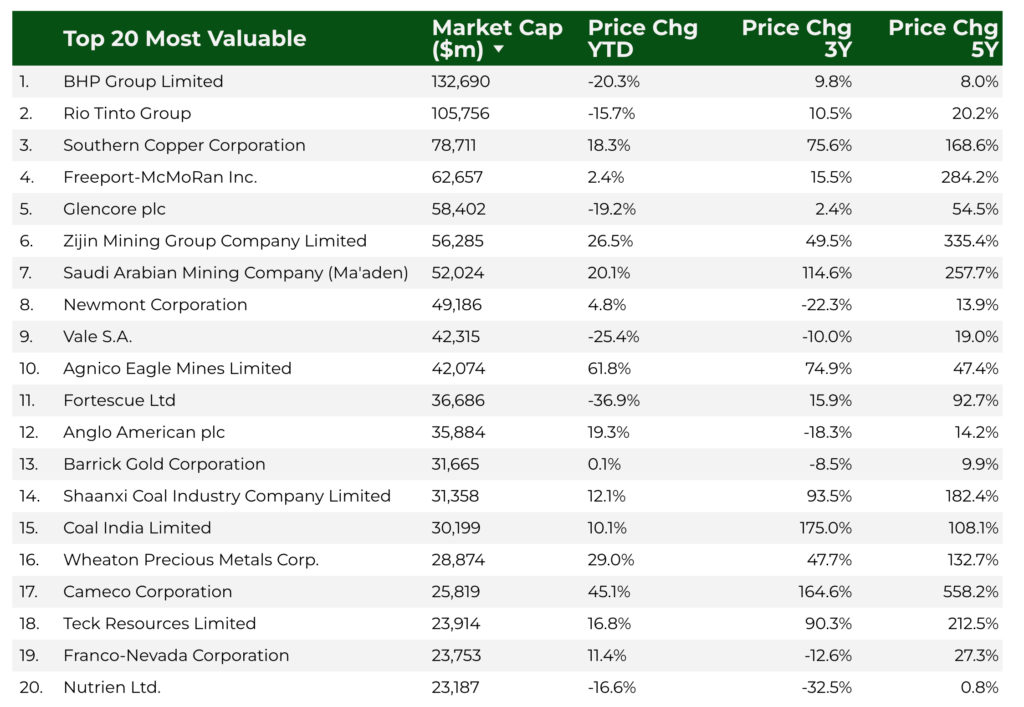

MINING.COM’s ranking of world’s 50 most valuable miners enjoyed a combined market capitalization of US$1.51 trillion at the end of Q3, up by single digits since the start of the year compared to rip-roaring broader U.S. and world markets.

Much of the drag on the index comes from the top – the mining industry’s traditional Big 5 – BHP (LSE: BHP; NYSE: BHP; ASX: BHP), Rio Tinto (NYSE: RIO; LSE: RIO; ASX: RIO), Glencore (LSE: GLEN), Vale (NYSE: VALE) and Anglo American (LSE: AAL).

With the exception of Anglo, which received a fillip from BHP’s approach, the stocks are deep in the red for 2024.

Together, the large diversified companies have lost nearly US$60 billion in value this year. One bad week – say copper retreats further and iron ore goes into double digits – would see them hit new 52-week lows. As the table shows, on a longer horizon their underperformance is even more startling.

In the past these stocks would consistently occupy the top five slots in the ranking, supported by vast asset portfolios covering a range of commodities across many regions.

In a boom and bust industry that was the key to success (if not survival) for companies that trace roots back many decades if not more than a century.

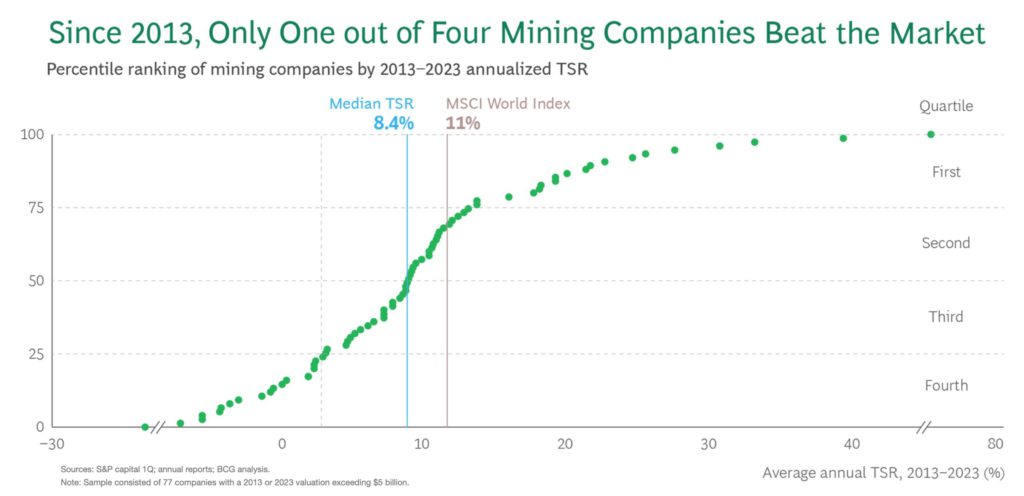

In a new report, Boston Consulting Group points out mining companies’ underperformance over the last decade when only about one in four companies delivered a total shareholder return (TSR) greater than the bellwether MSCI World Index and return on capital has been equally inferior:

“In their pursuit of growth, miners triggered price crashes that destroyed value. Given this performance, it’s not surprising that many investors commonly view mining companies as a “trade,” and that many active and specialist investors have abandoned the market.”

While the industry faces many common challenges including grade fade, geopolitical and policy uncertainty, particularly in permitting (more than 90% of exploration projects fail to turn into physical mines), climate disruption, and social pressures, BCG’s study of 77 companies across commodities and regions did find some industry darlings.

The top-quartile performers, many of them based in frontier jurisdictions, achieved an average TSR of 22% over the past decade (year-end 2013 through year-end 2023), outperforming the other industry participants by 18 percentage points.

While the first quartile were able to deliver stellar results through revenue growth and margin expansion, the mining majors have been unable to increase production to a meaningful extent, and margins shrank on average by around 20%, says BCG.

BCG sees two reasons for the struggles of the majors:

“First, their strategic choices have limited their degree of freedom. The focus on large, long-life, and low-cost assets may have improved their resilience through cycles, but good assets alone do not yield TSR outperformance. The focus on low-risk jurisdictions has constrained their ability to quickly develop and access high-grade ore.

“Furthermore, their reluctance to invest in smaller (and somewhat easier to build) mines has made it harder for them to adapt to development challenges and consistently deliver steady growth.

“In addition, diversification has increased the complexity of the majors’ businesses without an apparent corresponding payoff for shareholders. By complexity, we mean everything from organizational structure and business systems to different types of operations and value-chain integration.”

BCG’s remedies for this drag on performance include “having a playbook for value-creating M&A,” committing to new locations and adopting new mining methods:

The process of simplifying operations, shedding assets, spin-offs and the like is well underway at the top tier.

But as BHP’s failed takeover of Anglo, which indeed did come with demands for non-core asset sales and divestment from certain locations, shows value-creating M&A is easier said than done.

Be the first to comment on "Mining’s old guard needs strong medicine"