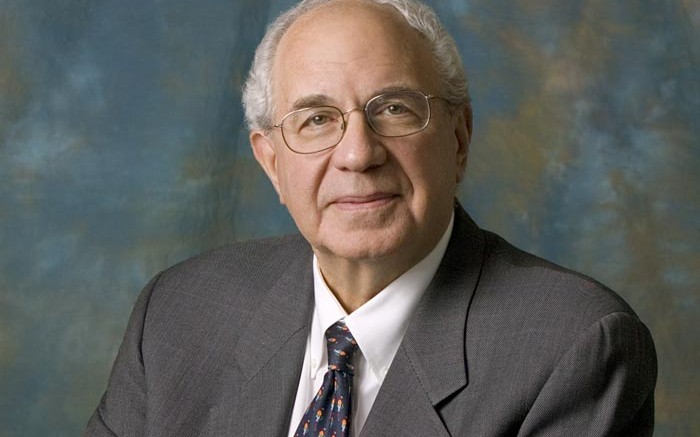

Ned Goodman, president and CEO of Dundee Corp., spoke about the perils of quantitative easing at the Toronto Resource Investment Conference on Sept. 12. He made the following remarks, as recorded by The Northern Miner, with part one having appeared last week:

Ned Goodman: The current challenges to the U.S. and world economies are the onset of longer-term problems of government; of consumer debt; too much debt; too much government debt; the rebalancing of that debt; and the structural inflation that will require serious stabilization.

And the cure for inflation is always deflation . . . and Mr. Bernanke is going to have that decision to make pretty soon. Now, nearly US$17 trillion will hurtle towards US$30 trillion soon, and soon to be 150% of the gross domestic product — those are David Stockman numbers — and that rules out any prospect of any great bargain that can happen. The U.S. fiscal collapse will likely play out incrementally, just like a Greek-Cypriot tragedy, and a carefully choreographed crisis over the debt ceiling, etc.

The precarious plight of the Main Street consumer has been obscured by the manner in which the state’s unprecedented fiscal and monetary medications have distorted incoming data and economic narrative. The monetary policy has become an engine of reverse Robin Hood distribution.

The question is: How much longer can the equity bull market last? ‘Just buy the equity market, whose central bank is the largest bond-buying program,’ is what they tell you — essentially the only piece of investment wisdom you needed in the last 48 months.

It’s been the Fed for the last four years, and in recent months the Bank of Japan’s turn. And [the Japanese] have just gone way out, and just said, ‘We’re going to create inflation.’ But it’s a matter of time before the narrative is exhausted and the pendulum swings back.

Mario Draghi said he’d do anything to keep the ball rolling, and he is doing everything and anything. There has been euphoria in the market. All this is causing people to be comfortable — everything is great. But those market corrections that occur remind me of the importance of maintaining proper portfolio diversification, which has been my career for years. The financial future is the largest threat that we are looking at.

But if you listen to Ben Bernanke, and all the other central banks, you’ll be told that inflation is not a worry. They want you to think that inflation is tame at 2%, a number they made up.

Now I remember in the 70s, when the Federal Reserve was working with the inflation rates and the inflation rates went and Arthur Burns, the then-central banker, said, ‘Well, the rate went up because there is a war in the Middle East and the price of oil is up, and since we have no intention of trying to fix the war in the Middle East or control the war in the Middle East, we take oil out of the inflation number, and energy has never been put back in. So the cost of energy is not in the inflation numbers.’

Then there was a big problem on the shores of the ocean in Peru. The anchovies didn’t show up. Every so often the anchovies decide they don’t want to get caught, so they don’t show up. Well, anchovies are the main feeding system in Latin America for the cattle and animals like that, so the net result was that food prices went up and the central bankers said, ‘We have no control over the anchovies, so therefore we have no control over the price of food — therefore we take food out of the basics of counting inflation.’ And they still haven’t put it back in. The anchovies come back every year and they still haven’t put it back in.

So food doesn’t count. And the way they look at food now, even if it did count, is that they look at what you can replace it with. So if you can replace a steak with some ground meat, they use ground meat instead of steak. So the numbers they are giving to create this euphoria are incorrect.

I passed by the Institute of Ludwig von Mises, and he’s a person that I have a lot of faith in reading and enjoy, and to summarize his work, he wrote that monetary expansions, like quantitative easing, confer no social benefit whatsoever.

In fact, the reason why the government and its controlled banking system tend to keep inflating the money supply is precisely because the increase is not granted to everyone equally. They like that. Instead, the whole point of the initial increase is the government itself and its central bank. Other early receivers of the new money are favoured new borrowers of the politicians or the bankers, but the banks themselves are contractors to the government. These early receivers of the new money, Mises points out, benefit at the expense of those down the line of the chain. It’s a ripple effect. They get the money last, if they get it at all.

So in a profound sense, monetary inflation is a hidden form of taxation — he was the first one to say that — and a hidden form of the redistribution of wealth to the government and its favoured groups.

So when interest rates can’t be dramatically lowered any further, or risk spreads get compressed, the momentum shifts, not necessarily suddenly, but absolutely gradually. Yields move mildly higher and spreads stabilize and move slightly wider. In such a mildly retiring, reflating world, unless you want to earn an inflation-adjusted return of minus 2–3%, which are offered by treasury bills in the U.S., then you must take risk of some form, and that’s what Bernanke did when he brought interest rates down to zero — he caused the market to move to a riskier source of investment money, and that’s why the stock market went up a little.

But we’re realizing today how accurate von Mises was in his predictions. He had these issues clear in his mind, and he implicitly warned central bankers of losing money to its real meaning and of exposing the economy to the risk of currency devaluation.

This then is a scary procedure, and now you saw in the newspaper an article put out by the Globe or Financial Post, I’m not sure which one. It’s called “A Little More Happy.” And you find that on a happiness questionnaire of 25 different countries, which include the U.S. and Canada, the U.S. people rank 17 out of 25, to be beaten by one, by Mexico at 16, to be beaten by another, Canada, who are six, I think we deserved it. But the United Arab Emirates were 14, so you have to think the people in the U.S. are recognizing exactly what is going on.

I think the best description of what’s going on is that we are living through a period of “botox economics.” Botox, of course, is a toxin commonly used to improve a person’s appearance. Sometimes it works. However, the effect is only temporary and it sometimes gives you some negative effects. As the global financial and excessive debt crisis rolls along, it does so with financial botox, and that’s what Mr. Bernanke is giving us: a flood of money from the central banks and governments covering up previously unresolved and perhaps serious problems, and you can’t forget the famous Will Rogers statement: “If stupidity got us into this mess, then why can’t it get us out?”

And that’s where we are. It’s all a bunch of stupidity today because we’re living in a time where there does not seem to be a way out of this global monetary madness. Everybody is over-indebted, everybody is tr

ying to deleverage, everyone is printing money — and we have no idea what the last piece is going to be.

So the gamble of the Federal Reserve policies to revive the U.S. economy — we may be heading in a direction that’s not totally comfortable. Ben Bernanke tries to operate on the basis that his job is really easy. I personally met with him, he does try to make it sound like it’s really easy, but when I asked the real difficult question and put my hand up, he doused me, and from then on he said, “Why don’t we let someone else ask a question?” And I never got another question.

The use of zero-interest rates and now unlimited quantitative easing, while easily understood, has already failed to deliver a better economic time for the U.S.

So let’s go back to visions — we are old enough here to have seen the pictures of people in the 1930s lined up for food banks. They had to line up, get a little coin that gave them the right to get a bowl of soup. And that’s the picture of the Great Depression that we had in the 1930s. And these images play an important role in our recollection of a particular memory, and that’s my mother telling me: “Do you know what happened in 1929?” She was a young girl in 1929, but she remembered that there was no money.

These images, they give us facts, they give us ideas for an event. For instance, consider this quick thought experiment. What is the first thing that comes to your mind when you think of the Great Depression? For me it was the iconic image of breadlines. Stretching for multiple city blocks, these images have been experienced through review of historical photos, some people have painted them, but they’re there and they’re in everybody’s mind.

If the collective tacit visualization of economic depression is that of breadlines, and today there are no visual breadlines, well then, surely things can’t be that bad. There are no breadlines. At the surface we do not see hungry Americans queued daily outside of soup kitchens.

Unfortunately, like many things in our modern world, the reality of modern breadlines is found not in a glance at a city sidewalk, but requires some thoughtful unearthing. Today in the U.S. there are breadlines. They are modern breadlines. They are long, the ranks are hungry and the lines are growing at a staggeringly rapid rate. We do not see these lines as they are, much like the modern world, digital. The symbolic image of a Great Depression-era breadline is woefully outdated. We need to update that technology because the world is quite different today than it was in the 1930s.

Contemporary American breadlines stem from something called the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), and there are 47.5 million people in 23 million households that receive SNAP benefits. That’s a lot of people. There are only 300-odd million that are in the country. It’s one out of six and a half Americans and over 20% of households that receive these SNAP benefits.

The legacy food-stamps program in the U.S. was rebranded — rebranded from food stamps to SNAP in the 2008 Farm Bill, just slipped in, nobody really saw it. And in this rebranding effort, all references to stamps or food coupons were removed from the legislation in favour of “credit,” or “electronic benefit transfer” (EBT).

In function, SNAP works as a monthly allowance whereby the beneficiary can use credits for food at SNAP-approved retailers. The beneficiary uses an EBT card, it’s like a credit card that acts as a debit card and draws down a monthly allowance. The card is meant to reduce the stigma of having to use stamps at a cash register — reduce the stigma of how badly the U.S. economy really is.

What it also does is hide from public view these people standing in line, because they don’t. They just shop and come to pay, they can buy lobster, they can buy anything they want, they are just limited as to how much credit they can get. So as the old technology of the 1930s — breadlines — is outdated, what is the modern e-breadline? What does it look like?

These 47.5 million Americans and 231,000 retailers — Walmart being one — but 231,000 retailers are authorized to accept these SNAP credit cards. So on average, that’s only 205 SNAP enrollees per retailer, but when you look further, the number is actually quite higher, because of the 231,000 SNAP retailers, only 16% are supermarkets, and yet supermarkets captured 82% of all SNAP redemptions — all SNAP credit cards — so 82% is going to food for people who are given this. I could go on about this. It’s scary because you don’t know about it.

The fact is that there is also something else. There’s a piece in the U.S. Act, which is called Section 8. And Section 8 allows people like the people who get SNAP credit cards to get a big portion of their rent paid if they live in a house that was previously under foreclosure, and they rent it. And that’s a way of getting the world to say, “The economy must be getting better, look at how well housing is doing.” So Blackstone goes out and buys several thousands of these foreclosed houses, mortgages them at Fannie Mae or Freddie Mac — a government mortgage — and then rents them to people who get Section 8 money, so the mortgage of course is guaranteed because it’s coming from the government. The mortgage is coming from the government, the rent is coming from the government, and the newspapers say, “Things must be good, the houses are going, they are being filled.” And it’s all bullshit.

So in my view, the dollar is about to become dethroned as the world’s de facto currency. The new president of China, Zhang Jiping, on his first visit on the day of his becoming president, requested to meet with Mr. Putin. And he immediately made a deal with Mr. Putin to get all the oil he needs, which he can buy in Renminbi.

A big part of the U.S. dollar being the world’s reserve currency is that at the time Nixon gave up the gold standard, he had Henry Kissinger as his advisor, and Dr. Kissinger very, very brilliantly convinced the Saudis that they must sell their oil in U.S. dollars, and that’s the way the U.S. dollar became the reserve currency of the world. Because everybody needed oil, and the only oil that was available in those days — we didn’t have shale, well, we had the shale but we didn’t know how to use it — but everybody needed oil and they had to buy it with U.S. dollars. And that’s how the dollar got to where it is today.

But it’s about to become dethroned as the world’s de facto currency. The closing words, which reporters reported from Zhang Jiping and Mr. Putin . . . were [that] . . . [they] have an international partnership that is important.

So you get China and Russia, and we’ve seen it now in the Syria thing. I could not think of something more ridiculous than trying to solve the Syria [crisis] by throwing a missile out from the Mediterranean and not knowing how many innocent people you’re going to kill because somebody else killed innocent people. It makes no sense at all. But that was Mr. Obama’s game and he was going to do it. Frankly, the Israelis have bombed Syria four times in the last 24 months. You never read about it in the paper. They took out their nuclear plant. They took out their three warehouses of chemical weapons. No need for a missile — they just sent jets with pilots who dropped bombs.

So the dollar is becoming dethroned as far as I’m concerned. In 1929 the supply of paper money was limited because it was backed by silver. Our current

U.S. dollar is backed by nothing. So people would use the dollar because if they turned it in, they’d get silver.

The Chinese have US$3.5 trillion, and they’re spending these dollars as quickly as they can, and it will not be long before the rest of us and the U.S. will be thinking likewise. I do, as we buy things to protect our future purchase power. In the 1930s everyone wanted U.S. dollars. Today everyone wants to get rid of them. Buying hard assets is what you will hear from many people in the business that I’m in.

We’re headed to a period of “stagflation” — maybe serious inflation, but stagflation for sure — and the U.S. will be losing the privilege of being able to print at its will the world’s reserve currency, a period that will be inflationary. And I can tell you that before that happens, it’s likely gonna become quite ugly.

We are living through an uncertain atmosphere and it’s all related to politics and money. And when interest rates and confidence turns overnight, investors are not rational. There’s no time when the truth takes place: China is the world’s largest debt holder, Japan is the second-largest debt holder and they may have to act in their own interest later on. Interest rates of 1.6% are not deserved by the U.S.

Problem is, the U.S. can’t afford to pay any more. So they don’t deserve their bond rating and they’re probably going to lose it. Discretionary spending in the U.S. is 36% of government spending, there’s an excellent chance that the U.S. will soon determine to be in a recession once again. I believe they already are. It’s highly likely that they will be in one soon.

Seventy-five percent of their new jobs are low wage, part-time, and often government inspired. Unemployment is understated, real unemployment is probably closer to 15%. Even Walmart is suffering. The end result of higher government spending and full employment policy and the U.S. Federal Reserve’s obsession with interest rates has been a roller coaster ride along a rising path — a rising path of inflation, which from time to time is brought under check, but each time it rises again . . . since time immemorial, sovereign kings, emperors or elected politicians of any sort have used magic money to acquire things or wage wars, and it just doesn’t work.

I’ll quote Jim Grant, and I’ll close: “You’ll rifle through history books in vain to find another monetary era like this one. A reserve currency made of paper, nothing else, is one novelty. A pan-European currency, also weightless, is a second. Chronic and immense imbalancing, a deepening deficit in America, is the third.”

Be the first to comment on "Commentary: Ned Goodman and the ‘Botox Economy,’ pt. 2"