As the world watched the Taliban assume control of Afghanistan this summer and the U.S. withdraw its last troops from the war-torn country, another conflict, thousands of kilometers away in the sub-Saharan Sahel region of West Africa, continued to claim victims in the tri-border region of Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger.

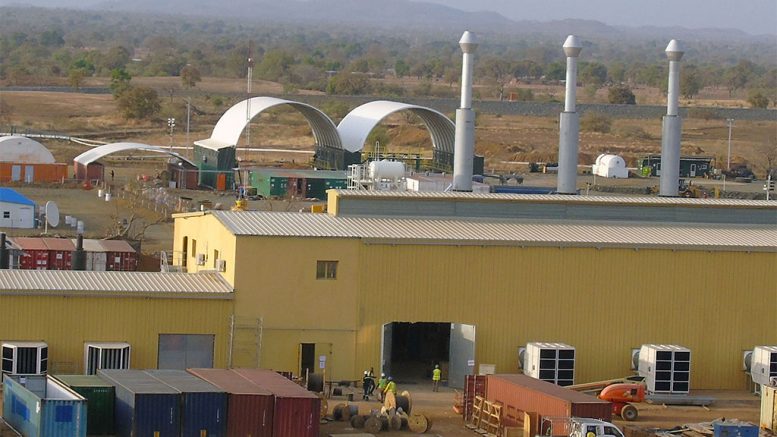

Last month there were attacks on civilians in Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger by militants likely associated with Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS) and the al-Qaeda-linked Jama’at Nasr al-Islam wal Muslimin (JNIM), and on Sept. 1, a convoy of Iamgold Corp. vehicles on its way to the Canadian company’s Essakane gold mine in northeastern Burkina Faso, came under fire from non-state militants. Fortunately no one was killed in the incident, about 330 km northeast of the capital, Ouagadougou. The company subsequently cancelled all convoys to and from the mine “until further notice.”

The ambush on Iamgold’s convoy — and the rising violence more broadly in the Sahel region — is yet another reminder of the risk mining companies take operating in a part of the world where thousands of people have been killed in recent years by Islamist insurgents and other militant groups.

In Burkina Faso, terrorists killed 80 people in an attack on a civilian convoy escorted by military police near the town of Arbinda in the northern province of Soum on August 19. Those killed in the attack included 59 civilians, six pro-government militiamen and 15 military police. Another attack in Burkina Faso on August 4 claimed the lives of 19 troops and 11 civilians. But the deadliest attack occurred on June 5, when Islamic insurgents massacred at least 132 people in the village of Solhan, a gold-mining area near Burkina Faso’s border with Niger.

According to the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project (ACLED), a U.S.-based non-profit that tracks political violence around the world, the strike on Solhan killed about 160 people and no group claimed responsibility. “JNIM has denied responsibility and condemned the attack, however, circumstantial evidence and reports point to local groups linked to JNIM, although the mass killing resembles recent ISGS mass atrocities and the group’s behavior in general.”

The United Nations provided emergency assistance and said that the dead in Solhan included “a high number of children.” Burkina Faso “is experiencing an unprecedented humanitarian crisis,” the UN said in a June 24 brief. “Currently, there are more than 1.2 million internally displaced people, 61% of them are children, compared to more than 136,000 displaced people during the same period in 2019—a tenfold increase in just three years.”

Meanwhile, across the border in Mali, fifteen soldiers were killed when their convoy was ambushed after a car bomb exploded on August 19. Another 51 people were killed on August 9 when Islamist militants attacked three villages near Mali’s border with Niger. The United Nations said in a statement that “the attacks against civilian populations constitute serious violations of international human rights law and international humanitarian law,” and were “liable to be classified as crimes against humanity.”

In Niger, armed assailants killed 37 civilians, including 14 children, on August 16.

The International Crisis Group notes that “jihadist attacks have increased fivefold since 2016 and inter-ethnic violence has ballooned.”

“Seven years after French forces deployed to the Sahel to battle jihadists in Mali, the region faces a profound crisis,” ICG says. The think tank also points out that “Sahelian states’ scaled-up military operations against jihadists in these rural areas have been part of the problem, helping trigger a disastrous cycle of violence against civilians. State security forces frequently ally with local militias, who often use the counter-terrorism fight as pretext to pursue their own local agendas. … As long as such violence grips the rural Sahel, jihadists will find opportunities.”

This year marks the tenth year of crisis in the Sahel, ACLED says, and jihadist militancy is starting to seep into other parts of the region. “The large-scale joint military operations by French and G5 Sahel forces have focused on the tri-state border region, an area of strategic importance,” ACLED said in a Jan-June 2021 report. ”They have certainly loosened the grip of jihadist militant groups and temporarily weakened their presence in the area. However, it is evident that over-concentration creates a ripple effect as these groups regroup and resume fighting elsewhere. This is particularly pronounced in the case of ISGS, which has become the deadliest armed group in the central Sahel since 2019.”

ACLED argues that the “steadily growing jihadist influence in eastern Burkina Faso has further exposed neighboring Benin to the prevailing militant threat,” while in southwestern areas of Burkina Faso, “the jihadists have become more aggressive toward the local population … as they seek to consolidate sanctuary and expand in the north of Ivory Coast.”

Amnesty International, citing statistics from ACLED, says more than 6,000 civilians have died in Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger between 2017 and 2021 due to the violence.

“The conflict in the Sahel has been characterized by serious human rights violations by all parties, including massacres of civilians by unaccountable armed groups. More than a million people have been displaced in the region, and the humanitarian crisis is fast becoming one of the worst in the world,” Patrick Wilcken, Amnesty’s head of business, security and human rights, said in an August 24 report. The report also noted that some of the arms sold by European countries (including Serbia, the Czech Republic, and France) to governments in West Africa, have fallen into the hands of armed groups, and identified Jihadists in possession of Serbian-made weapons. “In this increasingly dire context, states must act with extreme caution when considering arms transfers to the Sahel.”

For its part, the ICG says stabilizing the Sahel “requires a multi-dimensional approach” with the right balance of “military operations, security provision, development and better governance.” If the world wants to prevent the ‘failed state’ syndrome — it will require a combination of strengthening governance, institutions, and accountability; improving dialogue with locals; and long-term development work.

Be the first to comment on "Violence escalates in West Africa’s tri-border Sahel region"