A new study suggests that the electrifying the global vehicle fleet by 2050, the target year for net-zero emissions, will require an unrealistic ramp-up in copper production. But targeting 100% production of hybrid vehicles by 2035 instead of electric vehicles (EVs), could be more achievable.

Even without factoring in the energy transition, the world will need to mine at least 115% more copper than has been mined in human history pre-2018 to meet business-as-usual trends, according to the study, published by the International Energy Forum. In order to electrify the global vehicle fleet by 2050, would require even more copper — an additional 55% more new copper mines coming online by 2050.

Dr. Lawrence Cathles, an earth and atmospheric sciences professor at Cornell University who co-authored the study, said the findings point to a “disconnect” between the intentions behind decarbonization and the reality of the materials required.

Supply-demand disconnect

In short, the study — led by Dr. Cathles and Dr. Adam Simon, a professor of earth and environmental sciences at the University of Michigan — found that the rate at which the world is producing copper cannot keep pace with the increasing global demand for electric vehicles.

To quantify this disconnect, it gave projections of both supply and demand in a different way from prior studies (see below).

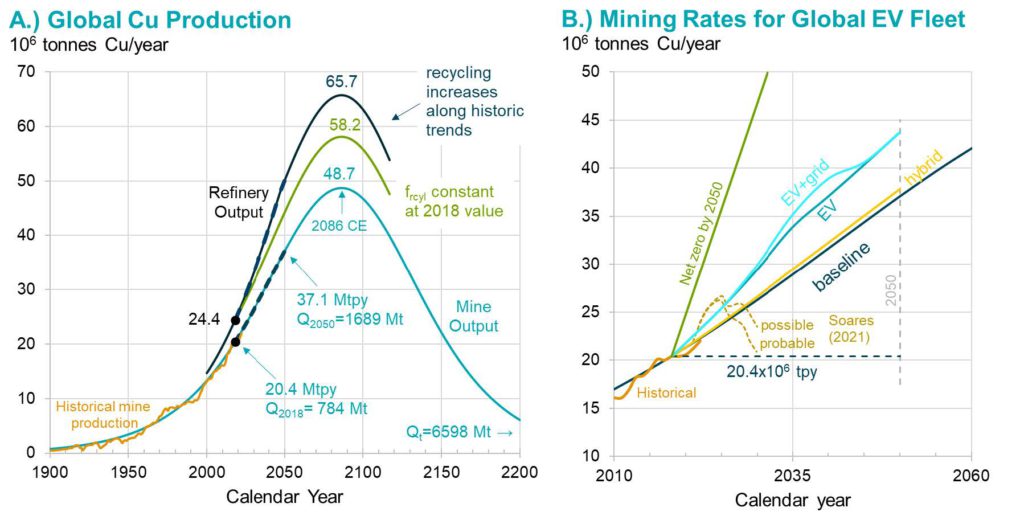

On the supply side, annual mine output is expected to increase by 82% (from 20.4 million tonnes to 37.1 million tonnes) by 2050, and so will the total supply, after accounting additions from copper recycling. However, all production estimates are set to peak around the year 2086 (mine output of 48.7 million tonnes), as shown in Figure A.

On the demand side, the study investigated several decarbonization scenarios and broke down the additional copper production that will be required under each case up until year 2050 (Figure B) .

The net-zero scenario displays the largest gap — requiring at least 194 mines or six new mines every year. On the other hand, the baseline scenario (business as usual) presents a more realistic challenge of 35 mines — about one per year (see chart below).

However, the authors also note that they have been optimistic in their projections. For instance, if copper recycling remains constant at its 2018 level rather than increasing as assumed, then the number of new mines required for baseline demand would be 43.

EV manufacturing goal

Even before reaching the 2050 net-zero target, the goal of 100% EV manufacture by 2035 will still require an unprecedented departure from the copper mining baseline, the report noted.

Historically, deviations in baseline production have been around 1 million tonnes per year. To meet projected EV manufacturing demand would mean a departure from the baseline of 5 million tonnes per year for over 30 years.

Taking recycling into account, this would mean a demand gap of 8.1 million tonnes in 2035 and 9.6 million tonnes in 2040, it added.

It is worth noting that the methods used in this study are identical to the one used by M. King Hubbert, who was famous for successfully predicting 30 years of U.S. oil production right up to when technologies such as directional drilling and hydraulic fracturing made it possible to produce natural gas and crude oil from shale and expanded the hydrocarbon resource.

Mining takes time

With increased mining activity, there also comes the question of whether the Earth holds enough resources to support this. The short answer given by the IEF report is yes.

Under the baseline scenario, about 1.7 billion tonnes of copper will be mined by 2050, which represents 26% of the total copper resource of roughly 6.7 billion tonnes estimated by the authors. Their total resource estimate is also close to the 5.6-billion-tonne figure given by the USGS.

If mining ever shifts to greater depths in Earth’s crust, the copper resource would grow further to 89 billion tonnes, and 241 billion tonnes may be recoverable from the seafloor.

Hence, there is plenty of copper available. But it is doubtful these resources can be mined fast enough to support current vehicle electrification targets.

New copper mines that came online between 2019 and 2022 took an average of 23 years from the time of a discovery to first production, the authors note.

“Within this long discovery-to-operation pipeline, we should see at least ten years of prospects (e.g. 17 prospects) with a combined production potential of 8 million tonnes per year in the pipeline to have any confidence we can meet the 1.7 major deposits per year discovery rate required for EV manufacture,” the authors wrote.

Hybrid: An alternative

In light of the findings, the authors of the report suggested hybrid vehicles as a better alternative for balancing the copper demands of electrification and the pressure placed on the mining industry.

“There is remarkably little difference between the amount of copper needed to manufacture hybrid electric rather than ICE vehicles,” they said, highlighting that hybrid electric vehicles require 29 kg of copper compared to 24 kg for an ICE vehicle.

“It would therefore be judicious to aim for a transition to the 100% manufacture of hybrid electric vehicles by 2035, rather than transitioning to the 100% manufacture of battery electric vehicles, which require 60 kg. The copper required for this transition is only slightly above baseline and does not require major grid improvements.”

“This is not a perfect solution, but it is a much more resource realistic one,” they emphasized.

Read the full report here.

Be the first to comment on "Transition to hybrids more ‘realistic’ than copper-hungry EVs — study"