SITE VISIT

Antofagasta, Chile — The word apoquindo means “meeting of the chiefs.” It’s an appropriate name for a company chaired by the former head of the world’s biggest copper producer, Chile’s Codelco, and managed by some of the biggest names in Chilean mining.

And while the shift from working for a major producer to a Vancouver- based junior is considerable, these players are sticking to what they know — Chilean and Peruvian copper — and have big plans for this little company.

Apoquindo Minerals (AQM-v) listed on the Venture board in late 2006. Since then the company has acquired four projects, completed almost 45,000 metres of drilling and considerable mapping, sampling, and geophysical work, produced two resource estimates, and raised almost $17 million through private placements.

The company’s main focus is the Apoquindo copper project, which is the collective name for the Elenita and Madrugador projects that sit 18 km apart in the heart of the Atacama Desert in northern Chile. The project is surrounded by copper mines, prompting Apoquindo’s chairman Juan Villarzu to describe the area as the “Park Place of copper.”

And Villarzu should know. He took over Codelco in 1994, when the copper giant was in the red because of a litany of problems, including out-of-control costs and low productivity.

During his nine years of leadership, Codelco re-emerged as a key copper producer, with a market capitalization of US$15 billion (up from $9 billion). Codelco now boasts a market cap closer to US$24 billion.

And his fellow directors are no slouches. Jozsef Ambrus, who holds a PhD in economic geology, has 40 years of mineral exploration and evaluation under his belt, 10 of them with Codelco. Bruno Behn also brings to the table 40 years of experience, his as a civil mining engineer and former manager of Codelco’s Salvador division. And Cesar Lopez, the president and CEO of Apoquindo, is a mining lawyer with practice founding and running an exploration-development company — he founded Centenario Copper (CCT-t), which anticipates production from its project in the Atacama in 2009.

As for Apoquindo, the company is weighing various options to achieve production within a year. Its drilling efforts expanded historical resource counts at Elenita and Madrugador, and geophysical signatures show the promise of more. Initial efforts in the hills of Peru are also returning grades worth following up.

Getting started

The Atacama Desert is known for its copper oxide manto-type deposits, and Apoquindo’s Elenita and Madrugador are no exception.

The Madrugador project covers 8.3 sq. km. In the mid-1990s Rayrock Minerals optioned a swath of claims around Madrugador, including the claims covering the Sierra Valenzuela deposit. Rayrock drilled 120 holes totalling over 17,000 metres on the Madrugador properties, culminating in a resource estimate of 3 million tonnes grading 1.18% copper.

Rayrock also calculated a resource estimate for Sierra Valenzuela, roughly 10 times the size of Madrugador. But in 1996, Rayrock and Joaquin Fontbona, the owner of Sierra Valenzuela, entered litigation. Rayrock decided to drop its option on the Madrugador properties while it fought — indeed, still fights — for Sierra Valenzuela.

From 1998 to 2004 the site saw no exploration and only sporadic small-scale mining. Then in 2005 a Chilean engineering company, Sociedad Proyecta, took on Madrugador. The company punched 100 short-track percussion holes into the one central claim block, searching for material grading better than 1% copper. Successful in its work, Proyecta then signed a three-year extraction agreement with the project’s two owners that allows for maximum extraction of 15,000 tonnes of material per month.

In late 2007, after a due-diligence period, Apoquindo signed a four-year option agreement with the owners. Apoquindo’s deal covers nine non-contiguous claim blocks, including the Proyecta block, that surround the contested Sierra Valenzuela deposit.

Less than 20 km north of Madrugador sits Elenita. The 7.5 sq. km property saw sporadic small-scale production from 1959 to 1993, at which time Princeton Chile optioned the ground. Princeton spent three years at Elenita, conducting drilling, sampling, trenching, and mapping. A preliminary study on the project at the time envisaged a heap-leach, solvent-extraction electrowinning (SXEW) operation handling 1 million tonnes of copper oxide ore annually for 10 years. With copper prices what they were in the early 1990s, the study found Elenita to be uneconomic.

Princeton turned the property back over to the Cespedes family, who left it idle for several years. In 2003, the family returned to the site and started up a small-scale mining operation, extracting roughly 1,500 tonnes of ore each month grading between 2.5 and 3% copper. That extraction was still going on while Apoquindo completed its due diligence on Elenita in 2007. The company signed onto the project before the end of the year.

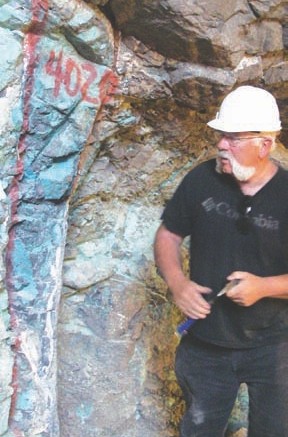

Small-scale extraction continues at both Madrugador and Elenita. From Apoquindo’s perspective, its impact on overall tonnage is minimal but the exploration advantage is huge.

“The workings they develop are invaluable,” says Alfredo Garcia, Apoquindo’s project manager. “It’s underground exploration without any of the cost.”

Proving up resources

In its first year holding Madrugador and Elenita, Apoquindo worked quickly. The company completed 42,000 metres of drilling, had geologists map and sample the project comprehensively, dug numerous trenches, ran a mobile metal ion (MMI) and ground magnetics surveys, and began metallurgical testing.

The company reached its first major milestone in mid-September, when it released the first National Instrument 43-101-compliant resource estimate for the two projects. Combined, Elenita and Madrugador host 25 million measured and indicated tonnes grading 0.8% copper, as well as 3.6 million inferred tonnes grading 0.7% copper.

Geologists had noticed that mineralization at Madrugador is more disseminated. That came through in the resource numbers, as Madrugador carries 10.7 million measured and indicated tonnes averaging 0.64% copper, plus 1.5 million inferred tonnes grading 0.6% copper.

Elenita hosts disseminated, bulk-tonnage mineralization near surface but also carries richer mantos mineralization at depth. The effect of the high-grade mantos is clear in the Elenita resource estimate: 14.2 million measured and indicated tonnes grading 0.92% copper and 2.1 million inferred tonnes averaging 0.73% copper.

It is thought the rich mantos at Elenita are the result of hydrothermal solutions proceeding from dioritic dykes and sills and emplacing stacked mantos and hydrothermal breccias in andesitic volcanics. The resulting ore zones strike to the northeast and are 5 to 30 metres thick.

And recent drill results, which came too late to be incorporated into the resource estimate, are likely to lift Elenita’s average grade higher. Expansion holes east of the known resource started to probe the untested eastward extent of the MMI anomaly. Results include 15 metres grading 3.43% copper and 22 metres of 2.26% copper in hole 123, 20 metres of 2.22% copper in hole 111, and 27 metres grading 1.36% copper in hole 112. While the results, especially those from hole 123, extend the limits of defined mineralization, management estimates that 70% of the anomaly remains untested.

Madrugador’s deposits consist of stockwork and stratabound mineralization distributed in irregular pockets and ore shoots emplaced in and near subvolcanic domes. The predominant oxide minerals are atacamite and chrysocolla; oxide mineralization reaches to 100 to 150 metres depth. Below the oxide layer the predominant copper minerals are sulphide minerals: primarily chalcocite, accompanied by bornite, chalcopyrite, covellite and pyrite.

The Madrugador area hosts a cluster of copper deposits, known as the Sierra Valenzuela district. Sierra Valenzuela, the 27-million-tonne deposit being argued over in court, is the largest defined to date. The resource that Apoquindo defined on its Madrugador claims essentially surrounds the contested deposit.

“Whoever wins that lawsuit will be talking to us,” Lopez says. “To put it all together is a very attractive idea.”

Apoquindo sees Elenita as carrying better economics, though both deposits are amenable to open-pit mining. The company is testing the metallurgy of a large number of reverse-circulation drill samples, while management feels out the best way to get both into production as quickly as possible.

As the company moves its defined deposits towards production, results from the MMI survey over the properties are pointing geologists to their next target. The results showed anomalies over the historic, and now proven, resources at Madrugador and Elenita. But the survey data also generated several other significant anomalies within the company’s claim blocks at Madrugador, which warrant further investigation.

Nice neighbourhood

With so much Chilean expertise within the company, it’s no wonder Apoquindo’s first goal was to find a copper deposit in the Antofagasta area. Antofagasta is a city of 350,000 on the northern Chilean coast, some 700 km north of Santiago. It’s a mining support city.

In the 1,200 sq. km of desert near Antofagasta, there are 11 sizable copper mines, plus many small-scale, family-run operations. Anglo American’s (AAUK-Q , AAL-l) Mantos Blancos mine sits 40 km east of Antofagasta; at Manto Blancos an SX-EW plant processes ore from two open pits hosting some 170 million tonnes grading 0.8% copper.

Majority owner BHP Billiton (BHP-N, BLT-l) runs the massive Escondida copper mine roughly 150 km southeast of Antofagasta, where reserves total 14 billion tonnes grading 0.7% copper feed. The mine produced almost 1.5 million tonnes of copper in 2007. Roughly the same distance to the northeast sits Chuquicamata, a Codelco op- eration tapping into 17 billion tonnes grading 0.6% copper.

The Atacama is also home to some higher-grade copper mineralization. Antofagasta Minerals (ANTO-l) operates the Michilla mine 60 km up the coast from the port city. At Michilla a 76-million-tonne deposit averages 1.56% copper.

The Apoquindo copper project sits directly in the middle of this mega-copper district, about 80 km northeast of Antofagasta.

The thriving copper industry in this barren desert means infrastructure is, for the most part, not a problem: the Pan American Highway runs within 20 km of Apoquindo’s properties; the main line of the state-owned northern rail- road lies just 10 km from the properties; power is available in the village of Baquedano, 30 km south; and natural gas is nearby.

The challenge is water. This is world’s driest desert — there’s no rain or snow, and so essentially no plant or animal life. However, all mining operations need water, which means several pipelines have been built or are planned. The most-relevant one for Apoquindo is a salt-water pipeline that Antofagasta Minerals is building to supply its Esperanza project. That pipeline will come within 40 km of Apoquindo’s properties and carry twice the amount of water needed at Esperanza, because Antofagasta Minerals wants to be able to sell the excess flow.

In addition, Antofagasta city recently announced plans to build a major desalination plant that will supply potable water for the whole city. With added capacity available there as well, the price of water for mining operations in the area is expected to come down.

But water availability is not the only benefit that comes from working in the world’s copper centre. For Apoquindo, the key benefit lies in the fact that many of the area’s major mines have a little extra room available at their SXEW plants.

“So many of these plants have excess capacity right now and they’re just ready to take our feed,” Lopez says. He explains that Mantos Blancos, which processes 4 million tonnes of ore annually to produce over 90,000 tonnes of copper, has the current capacity to produce another 25,000 tonnes of copper each year.

That means that Apoquindo’s initial production plans don’t require building a costly SX-EW plant, nor would the company need to source sulphuric acid to run that plant. While the latter may not seem a major concern, sulphuric acid is in very short supply in Chile and is therefore rather pricey.

Instead, the company is planning on building or buying a facility to crush ore from Elenita and Madrugador, which would then be loaded onto leach pads for processing. The pregnant leach solution that drains from the pads can then be pumped to whatever SXEW plant wants to buy it.

Management is currently reviewing a scenario wherein Apoquindo could start crushing, leaching and pumping enough solution to produce 5,000 tonnes of fine copper annually in the short term. The plan would then be to increase production to 20,000 tonnes of fine copper within two to three years.

To develop or rehabilitate such an operation would cost roughly one-fifth the capital outlay needed to also build the SX-EW plant. And Apoquindo would be paid just over 80% of the copper price for its pregnant solution. The company is already in talks with the owners of several SX-EW plants in the area.

This focus on minimizing development costs is clear in talking with Villarzu. “We want to take advantage of all the opportunities we can to externalize labour,” he says. “For example we are not going to have our own trucks; they will be owned by contract miners. Along with saving money, it will mean we can be in production in three years, maybe less, instead of many more.”

Peruvian ventures

Then there are Apoquindo’s projects in Peru. The company is working on two exploration ventures there: the Huarman gold-silver prospect in the department of Ancash, west-central Peru, and the Pachagon copper play in La Libertad, northwest Peru.

Huarman sits in the centre of the Central Peru polymetallic skarn and replacement belt, which hosts Barrick Gold’s (ABX-T, ABX-n) 7-million-oz. Pierina gold mine. Just as at Pierina, the principal targets at Huarman are manto and cross-cutting high-sulphidation breccias within the Calipuy volcanics.

The area has a long history of mining. For the last 25 years, artisanal miners have pulled high-grade rock from the two main, known veins at Huarman, El Rey and El Principe, as well as from the San Juan open-pit and underground operation. The San Juan workings tap into an east-dipping tabular polymictic volcanic breccia that crops out along a 500-metre strike length and across 100 metres width.

One of Apoquindo’s first moves was to conduct an induced-polarization-chargeability survey. The results show strong, coincident low-resistivity and high-chargeability anomalies associated with the known breccias at San Juan. Interestingly, these anomalies extend considerably to covered areas to the north, and under a mountain to the south.

Initial sampling returned promising results. On average, 350 rock-chip samples from surface showings of the main breccia returned 0.56 gram gold per tonne and 28 grams silver per tonne. Rock-chip samples from the San Juan workings showed better grades: 115 samples returned average grades of 1.4 grams gold and 36 grams silver.

In 2008 Huarman saw its first drilling, as Apoquindo completed a 2,200-metre program. The first two holes into the volcanic breccia returned lengthy mineralized intercepts. Hole 1 cut 164 metres grading 0.33 gram gold and 13.73 grams silver from just 16 metres depth. And hole 2 returned 1.13 grams gold and 43.6 grams silver over 54 metres, within a 110-metre intercept from surface grading 0.77 gram gold and 25 grams silver. Remaining drill results are pending.

The 7.6-sq.-km property enjoys good access from the Lima-Huaraz highway, even though the average elevation on site is 4,400 metres. Apoquindo, through its wholly-owned Peruvian subsidiary Minera KoriTambo, optioned the property from the private Peruvian company Minera Surmasa in January.The price, in staged payments that are not yet complete, was set at $2 million. Surmasa will retain a 1.5% net smelter return royalty that KoriTambo can purchase for $2.5 million.

In May 2008, Apoquindo signed an option agreement on the Pachagon porphyry prospect, where the principal target is leachable copper ore in secondary chalcocite that’s hosted in both sedimentary rocks and granodioritic porphyry.

In their due diligence work, Apoquindo’s geologists noted mineralized, moderate-to-strong phyllic alteration over a 5-sq.-km area. They identified multi-percentage secondary copper, as chalcocite and copper oxides, in old artisanal workings that went after a chalcocite-blanket outcrop on a mountainside.

In 1995, Altai Ventures drilled seven short holes at Pachagon and in 2002 Anaconda drilled another three, both bouts aimed at that chalcocite blanket. Results included some short, high-grade intercepts, such as 4 metres of 2.63% copper and 12 metres of 1.02% copper, plus some longer hits, including 74 metres averaging 0.44% copper and 50 metres of 0.57% copper.

Tom Henricksen, Apoquindo’s chief geologist and the head of its Peruvian projects, sees potential for 200 million tonnes at Pachagon. “If that happens and the average grade is 0.5%, I’d be happy,” he says. “The mineralization is along a steep slope, which would make mining easy, and it’s predominately chalcocite so it’s leachable.”

The optimism comes not only from the promising results to date but because Apoquindo managed to consolidate a project that had been divided among several owners up until now. Henricksen says that as soon as they merged the claims into one project, people started knocking in their door.

“The beautiful thing about Apoquindo is that you’ve got these solid copper oxide projects in Chile but then you also have this true blue-sky potential as well,” Henricksen says.

The company planned to complete a few more holes, to bring the drilling to 2,500 metres, but stopped the program early because of current market conditions. It still has to make payments on the option agreement, which requires a total of US$4.5 million over four years. Now the company plans to search out a partner for the project or just wait until financial conditions improve to continue work.

At presstime, Apoquindo shares traded at just under 50. The company has a 52-week trading range of 30 to $1.50 and has 28.9 million shares issued.

Be the first to comment on "Apoquindo copper chiefs see near-term production"