A lifelong dream is beginning to come true for Gordon McCreary, former vice-president of corporate affairs for

McCreary’s involvement with the Mary River deposits began 25 years ago, when he wrote his MBA thesis on the project. At the time, the world was awash in iron ore and there was little need for another producer, especially one in as challenging a location as Baffin Island. So McCreary turned his attention elsewhere.

But circumstances changed. First, China developed a huge appetite for steel; indeed, the country is now gobbling up about 30% of the world’s iron ore supply, creating strong demand for new sources of ore. Second, Russian and Scandinavian shipbuilders improved the technology needed to move large tonnages of ore from the High Arctic.

Recognizing an opportunity, McCreary left Kinross earlier this year to take project owner

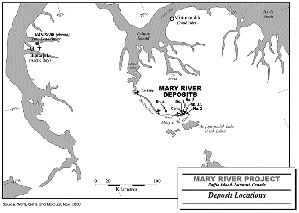

Baffinland’s advanced exploration and development program is expected to conclude with a feasibility study within three years. During the remainder of 2004, the junior will complete metallurgical testing and outline the strike and dip extensions of the No. 1 deposit, where an indicated resource of 116.7 million tonnes grading 68.3% iron lies. The 5,000-metre, 25-30 hole program will also test three other deposits, Nos. 2, 3 and 3A, which have never been drilled before but which show potential for high-grade ore.

Baffinland’s medium-term objective is to more than double the resource at Mary River and obtain market acceptance for the ore through metallurgical test work. Once in production, the company expects to be in the lowest quartile of producers in terms of cash costs, owing to the high grade of the ore and the simplicity of operations. Most of the world’s major iron ore mines in Brazil and Australia have grades ranging from 52% to 66% iron, as well as expensive processing requirements.

The Mary River deposits are in the Committee Belt, an assemblage of granite-greenstone terranes and rift basin sediments and volcanic rocks. Rock units of the Mary River Group include iron formation, clastic metasediments, felsic to intermediate metavolcanics, mafic and ultramafic rocks, and intrusives. The iron formations include massive magnetite and hematite and banded chert ironstone, as well as garnet and tremolite granofels, calc-silicate rocks, and carbonate.

The deposits were discovered by Murray Watts of Watts, Griffis and McOuat fame during an aerial reconnaissance survey in 1962. Subsequent drilling outlined a significant, high-grade resource. A feasibility study indicated that it would cost $100 million to build an open-pit mine with annual production of 2 million tonnes — too expensive for the former owners to finance privately.

Government aid

“Because of the capital and construction cost factors outlined, . . . the success of Baffinland’s operation is dependent on financial aid from the government of Canada,” says a report given to those who visited the site in the summer of 1966. Among the guests attending that day were Bank of Canada Governor Louis Raminsky, then-Minister of Northern Affairs and National Resources Arthur Laing, and reporters from major periodicals such as the New York Times and Time.

Later, Hudson Bay Mining & Smelting (HBMS), the largest shareholder (47.3%), took over management of the project. But according to McCreary, the South African producer got cold feet when the federal government, first under Lester Pearson and later under Pierre Trudeau, refused to help finance the infrastructure required to build a mine there. “There was a strong feeling at the time that Canadian resources should be for Canadians,” he explains.

And so, other than the occasional expression of interest, the project has remained dormant ever since.

“People forgot about it, people died, and the information was so old you couldn’t even find it on the Internet,” says McCreary.

But he and his partner, Richard McCloskey, president of

If all goes according to plan, the Mary River deposits could be in production by 2010 at the annual rate of 10 million tonnes over a lifespan of at least 25 years. “At that rate, you’ve created most of the economies-of-scale without aiming for a project so big it can’t be financed,” says McCreary.

Baffinland is focusing on developing the lump ore potential of the deposit. Lump ore does not require grinding, the biggest cost in an iron ore operation, but can be fed directly into blast furnaces after being crushed and screened. Lump commands a higher price on the market than either sinter (agglomerates made from concentrate) or pellets (agglomerates of fines). At present, sinter represents about 62% of global imports, whereas lump takes just 19%, an imbalance attributed to limited supply rather than lower demand for lump.

Because the Mary River deposits are a mix of hematite and magnetite ores, only about 34 million tonnes (the hematite portion) of the current, 130-million-tonne resource can be mined as premium lump ore, according to Strathcona Mineral Services, which recently published a review of the project. Another, 50-million-tonne portion (the magnetite component) with a sulphur content above the allowable limit of 0.05% would have to be blended or excluded from the resource base. The remaining low-sulphur tonnage, a mix of hematite and magnetite, could be crushed into a high-grade fines product.

“The drill program is designed to figure out what the split between lump and fines is going to be,” says McCreary. “By stepping out in the drilling, we’re seeing hematite in areas we didn’t expect.”

The distinction is important because the Mary River product will have to rank among the world’s best to offset the challenges associated with the project’s location.

In order to reach proposed European markets, Baffinland will need to build a rail line running either 100 km north to Milne Inlet or 120 km south to Steensby Inlet, as well as a port facility. From the port, iron ore will be loaded unto ships bound for Rotterdam, a journey of at least 5,000 km The company plans to extend the 4-month shipping season used by the nearby Nanisivik mine to 8-9 months by using ice-breakers when necessary.

Although it is too early to calculate capital costs, especially for the shipping component of the project, McCreary predicts it will be “a big number,” in the hundreds of millions of dollars.

Negotiations

Another challenge will be negotiating the fragmented permitting process in Nunavut, a territory still in its infancy. So far, the Nunavut government has shown support for the project, but Baffinland expects permitting to take at least 18 months. In developing an Inuit impact and benefit agreement, the company is emphasizing the multi-generational nature of the proposed mine.

And there is a chance the Mary River development may be too late to take advantage of the current tight market conditions. A recent report by the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development said capacity expansions and new projects could tip the iron ore market i

nto surplus by the end of the decade.

But if the company can manage these challenges and get its timing right, Mary River will have two competitive advantages: it has higher grades and is closer to European markets than the main iron ore producers in Brazil and Australia. Also, because the export market is controlled by a mini-cartel of three main producers [Brazil’s CVRD and Australia’s Rio Tinto (RTP-N) and BHP Billiton (BHP-N)], steel companies will welcome a new supplier.

“The steel mills want the flexibility to buy from whomever they want so that they can mix and match [product] to cut costs,” says McCreary.

Finally and most importantly, iron mines tend to be the unheralded cash cows of the mining industry. Rio Tinto’s Hamersley operation in Australia, for instance, has averaged a 27% return over the past 20 years and the iron ore group as a whole provides about 30% of Rio Tinto’s total earnings.

“A good diamond mine is twice as good as a good gold mine, but a good iron ore mine is worth both combined,” says Zurowski.

— The author is a Toronto-based geologist and freelance writer specializing in mining and the environment.

Be the first to comment on "Baffin Island’s rich iron deposits attractive again"