VANCOUVER — In 1971, two geologists from the Geological Survey of Canada, Jim Monger and Charlie Rouse, proposed an idea that helped radically shape how we view the geological history of Western Canada today.

Rather than using the more widely accepted theories of facies changes or extensive seaways to explain the presence of certain fossils in the rocks of central B.C., they proposed that the rocks, and the fossils in question, must have migrated across the Pacific Ocean to their present location. Their revolutionary idea would come to explain a geological story that was set in motion 180 million years ago, when the opening of the Atlantic Ocean drove the ancestral North American continent westwards.

The movement ignited subduction beneath the western margin of the continent, and a number of offshore volcanic island chains and basins of sedimentary rocks were docked and thrusted onto the landmass.

Paleomagnetic studies have shown that over the last 150 million years, a vast area of ocean floor — a distance equal to one-third of the earth’s circumference — has disappeared beneath North America. As a result, enormous volumes of magma, generated by the subducting slab, were injected into the overlying crust.

These fault-bounded geological landmasses, known as terranes, occur within (but are not limited to) northwest-trending geographic belts that extend across much of B.C. and the Yukon. From east to west these are called: Foreland, Omineca, Intermontane, Coast and Insular.

The accretionary collage contains pre- and post-collisional precious and base-metal deposits, ranging from coal, oil and gas (mainly in the Foreland belt), through lead, zinc, silver and tungsten (mainly in the Omineca belt), to copper, molybdenum and gold in the belts to the west.

While most deposits across Canada tend to cluster within a defined district, the world-class deposits of B.C. and the Yukon are often found like pearls on a string, following the linear geological terranes and structures that host them.

Physiographic belts and terranes of Western Canada and Alaska. Credit: Wikipedia (left), Yukon Geological Survey and British Columbia Geological Survey (right).

(Download a higher quality version of the terrane map here)

The Foreland Belt

Found in the eastern reaches of B.C. and the Yukon, the Foreland belt consists of ancient sedimentary rocks that were deposited along the western edge of the North American continent up to 1.4 billion years ago, though younger, 33-million-year sedimentary sequences also occur.

During mountain building, peat bogs that once formed on the seaway margin were buried, weakly metamorphosed into coal and later exhumed by faulting. Two main coal fields in B.C. — the East Kootenay and Peace River — are recognized in the region, where resources are similar in quality to many Permian-age coals exported from Australia.

The Omineca belt

Occupying the zone between the Foreland belt in the east, and the Intermontane belt in the west is the Omineca belt. Much like the Foreland, the Omineca contains the remnants of ancestral North America, however the rocks are complexly deformed and highly metamorphosed, representing the deeper, exposed roots of a mountain chain created between 180 and 60 million years ago.

The belt is divided into four main terranes — Yukon-Tanana, Cassiar, Slide Mountain and Kootenay — all of which contain rocks between 2 billion and 180 million years old.

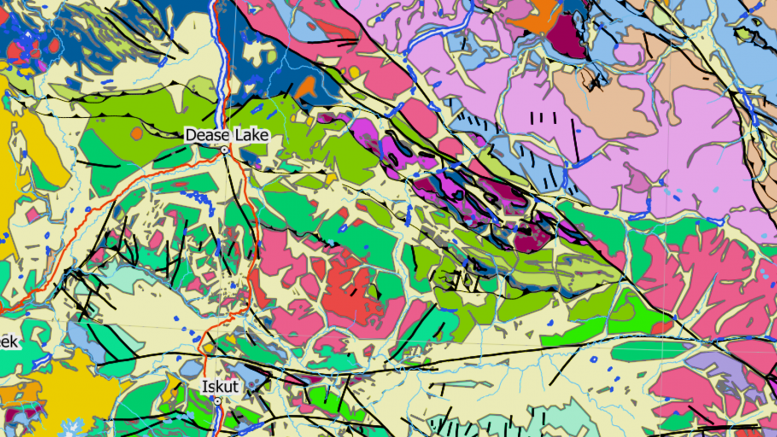

Select deposits and districts in B.C. and Yukon relative to geological terranes. Credit: Yukon Geological Survey and British Columbia Geological Survey. Modified by The Northern Miner.

Select deposits and districts in B.C. and Yukon relative to geological terranes. Credit: Yukon Geological Survey and British Columbia Geological Survey. Modified by The Northern Miner.

Teck Resources’ (TSX: TCK.B; NYSE: TCK) historic Sullivan lead-zinc-silver mine, near the town of Kimberley in south-central B.C., is the most standout deposit in the Omineca belt. Hosted within a package of sediments belonging to the Kootenay terrane, the 1.4 billion-year-old Sullivan deposit has yielded more than 17 million tonnes of zinc and lead, and 285 million oz. silver, valued at $20 billion, over its century-long mine life.

Sullivan serves as a textbook example for sedimentary-exhalative deposits, whereby metal-rich fluids released from hydrothermal vents and fissures along a seafloor migrate through permeable, water-laden sediments, and deposit metals in their wake.

Similar deposits are also found in the Yukon, such as the Selwyn Chihong Mining’s Howard’s Pass zinc-lead project at the border with the Northwest Territories, where resources amount to 144.8 million tonnes of 5.5% zinc and 2.1% lead, with another 220 million tonnes of potential.

Another region in the Kootenay terrane is the Barkerville gold camp near the town of Wells in south-central British Columbia. The camp saw over 3.1 million oz. placer gold and 1.3 million oz. lode gold from historical production, whereas modern explorers, such as Barkerville Gold Mines (TSXV: BGM; US-OTC: BGMZF)v, have outlined over 4.8 million oz. gold in resources from nearby bedrock sources.

Mineralization in the Barkerville camp occurs as replacement pods and veins within Proterozoic-aged (2.5-billion-year to 540-million-year) sedimentary rocks, focused along the high-strain deformation corridors that bound the Kootenay terrane with the Slide Mountain terrane in the east. The relationship between deformation and gold pegs the mineralizing event at 145 million years ago.

The Intermontane belt

This belt is divided into Quesnellia in the east, Stikinia in the west, and oceanic crust belonging to the Cache Creek terrane either thrust on top of the other terranes or wedged in between. These terranes were the first, truly exotic rocks to have docked onto North America, having started as volcanic arcs farther out in the ocean basin.

How the terranes arrived at their present position is an enigma among geologists. Some say the Cache Creek docked onto the Quesnellia and Stikinia arc — which at the time formed a continuous belt — 230 million years ago, outboard of ancestral North America.

By 150 million years ago, the complex pushed into the continent, and the northern tip of the Quesnellia-Stikinia arc bent backwards onto itself in a counter-clockwise motion, while the oceanic crust thrusted up in-between.

This “isoclinal bend” theory helps explain why the two arcs — which are almost geologically identical — are separated by a foreign piece of oceanic crust, with fossils that indicate a far-eastern Pacific origin.

Most of the porphyry copper-gold and related epithermal systems found in B.C. and the Yukon formed between 220 and 175 million years ago — before the landmass was accreted onto North America — in a setting similar to the present-day Indonesian and Philippine volcanic arcs.

The most notable examples are found in the northwest parts of the Stikinia terrane, a region known to many as B.C.’s “Golden Triangle.”

The volcanic arcs in Indonesia and the Philippians are the modern-day analogues of the Stikinia and Quesnellia arcs of Western Canada before they were accreted onto the North American landmass. Complex plate interactions lead to a variety of deposits, including porphyry-epithermal and volcanogenic massive sulphides as the arcs develop. Credit: Google Earth.

The Golden Triangle encompasses a number of world-class, gold-rich porphyry deposits, such as Teck’s Shaft Creek, Imperial Metals’(TSX: III; US-OTC: IPMLF) Red Chris copper-gold mine, and Seabridge Gold’s(TSX: SEA; NYSE: SA) KSM camp — the latter containing a whopping 38.8 million oz. gold and 10.2 million lb. copper, at grades of 0.51 gram gold per tonne and 0.2% copper, in proven and probable reserves.

Hydrothermal fluids off-gassing from underlying porphyries spurred the growth of Pretium Resources’ (TSX: PVG; NYSE: PVG) Valley of the Kings epithermal gold deposit — where proven and probable reserves stand at 8.1 million oz. gold in 16.6 million tonnes grading 16.1 grams gold — and Skeena Resources’ (TSXV: SKE; US-OTC: SKREF) 1 million oz. Snip gold deposit and former mine.

Stikinia’s volcanic pile is also prospective for volcanogenic massive sulphide (VMS) deposits, as seen at Barrick Gold’s (TSX: ABX; NYSE: ABX) Eskay Creek, which produced 3.3 million oz. gold and 180 million oz. silver at grades of 49 grams gold and 2,406 grams silver over its mine life.

Teck’s open-pit Highland Valley copper mine near Kamloops, B.C., is a star example of porphyry deposits in the Quesnellia terrane, having yielded more than 1.1 billion tonnes of ore in its lifetime.

Other porphyry deposits in this eastern terrane include KGHM Ajax Mining’s Ajax copper-gold project, Imperial’s Mount Polley copper-gold mine and Centerra Gold’s (TSX: CG; US-OTC: CAGDF) Mount Milligan copper-gold mine in the north.

After the Stikinia-Cache Creek-Quesnellia landmass docked onto North America, it buckled, deformed and metamorphosed rocks belonging to the Foreland and Omineca belts.

This tectonic event not only kicked-off gold mineralization at Barkerville, but also created B.C.’s Cassiar gold district, and the prolific 20 million oz. gold Klondike placer gold fields and the White Gold district in the Yukon.

Explorers at Goldcorp’s Coffee gold project in southcentral Yukon. There are at least two main mountain-building events that led to orogenic gold mineralization in the Yukon. The first event occurred after the Quesnellia-Stikinia-Cache Creek landmass docked onto the North American continent about 150 million years ago, giving way to the 20 million oz. Klondike Gold Fields, and another event after the Wrangellia-Alexander terranes were accreted about 100 million years ago, giving way to mineralization seen at Goldcorp’s Coffee gold project. Credit: Kaminak Gold.

The Coast and Insular belts

About 100 to 115 million years ago, offshore volcanic terranes belonging to the Insular belt — Wrangellia and Alexander — smashed into western Stikinia, compressing the metal-rich arc by more than 160 km, or nearly half of its width. Many of the deposits were highly deformed, and most structural clues that explorers use to home in on mineralization were either overprinted or reactivated, making them more challenging to find.

This Cretaceous-age, mountain-building event drove gold-rich hydrothermal fluids into parts of the Yukon, most notably at Goldcorp’s (TSX: G; NYSE: GG) Coffee project, where resources total 4.9 million oz. gold.

As the accreted landmass towered to new heights, subduction beneath the landmass picked up speed and the volcanic crust was injected with enormous volumes of granitic magma and volcanism for 50 million years.

During this period, pulses in magmatism farther inland created a range of porphyry copper-gold deposits, such as Imperial’s Huckleberry and Taseko Mines’ (TSX: TKO; NYSE-MKT:TGB) Prosperity deposits in B.C., and Western Copper and Gold’s (TSX: WRN; NYSE-MKT: WRN) Casino project in the Yukon.

This mineralizing event happened in response to the Laramide orogeny, a period of intense deformation between 80 and 35 million years ago, which produced porphyry and related deposits across the U.S., Mexico and beyond.

As time passed, the tops of the mountain chain near the modern-day B.C. coast eroded away, including any potential porphyry-style deposits, and the granitic core — known as the Coast belt — was exposed.

The Stawamus Chief on the Sea to Sky highway, outside Squamish, B.C., is the granitic core of a volcanic mountain chain that developed after the Wrangellia-Alexander terranes docked onto North America some 100 million years ago. Credit: Destination British Columbia.

Bordering the Coast belt in the west, the Insular belt forms the foundation of Vancouver Island, Queen Charlotte Islands, the northwestern tip of B.C., southeast Alaska and southwestern Yukon. Its volcanic crust ranges from 600 million years old to recent, and is known for its world-class VMS polymetallic deposits, such as Nyrstar’s Myra Falls mine near Campbell River, Vancouver Island, and the Windy Craggy deposit in B.C.’s extreme northwest.

The western margin today

In the last 50 million years, the structural regime off the coast of modern-day B.C. has transitioned more towards sideways-slipping faults than subduction, with tremors and earthquakes taking precedent over volcanism and mountain building.

Active mineral projects in British Columbia 2016 against geological terranes. Credit: Ministry of Energy and Mines, British Columbia Geological Survey.

Image also available here.

Active mineral projects in the Yukon in 2015 with geological terranes. Credit: Yukon Geological Survey.

Image also available here.

Be the first to comment on "When the east pushed back: The geology and metal districts of BC and Yukon"