The world is at the start of an exponential upswing in demand for the suite of technology metals as a global top-down push for the energy revolution accelerates, Ryan Castilloux, managing director of Adamas Intelligence, tells The Northern Miner.

He says that despite the figures coming off a lower base in 2020 due to the coronavirus pandemic, China and the European Union saw exponential demand growth for critical minerals in the first five months of the year despite the rolling shutdowns last year.

“Coming into 2021, with the change of administration in the US, we now see the US recommitting itself to the Paris Climate Agreement and laying out its aggressive targets for electrification of vehicles in the decade or two ahead. That adds even further strength to the narrative coming out of last year and gives us confidence that we’re now really at the beginning of strong, steady growth for both the bouquet of battery metals and materials but also other rare metals, including rare earth elements that stand to benefit from ongoing electric vehicle demand growth,” says Castilloux.

According to him, the move from prior projections about future demand growth has been so strong, it’s in fact, overshooting those forecasts.

“We’re seeing a lot of yesterday’s projections coming to fruition, and in most or all cases, I would say, likely exceeding the projections, given the top-down push that we see in key markets like China, Europe and the US, where governments have gotten behind electrification. They are pushing it forward, rather than simply allowing the market to grow organically, which was probably more of an accurate reality five years ago or so.”

With US$2.5 trillion being earmarked in US President Joe Biden’s plan in the American Jobs and Infrastructure plan, should it be passed, and more than a trillion euro earmarked in Europe’s Green Deal, the incremental future demand for these metals become material.

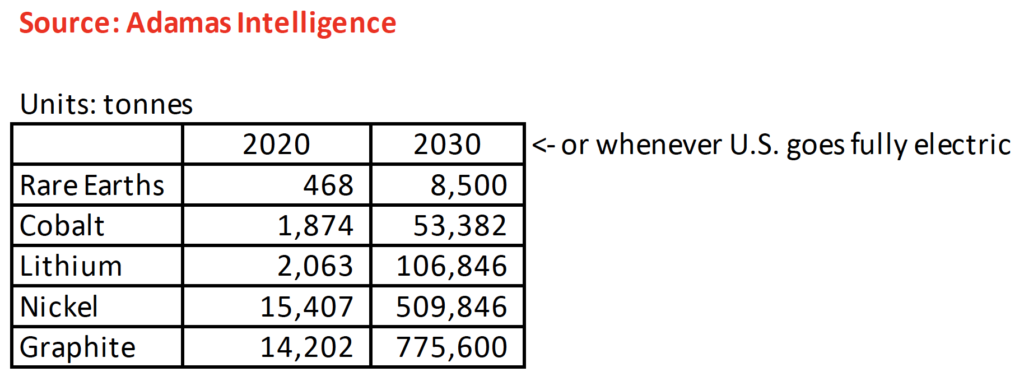

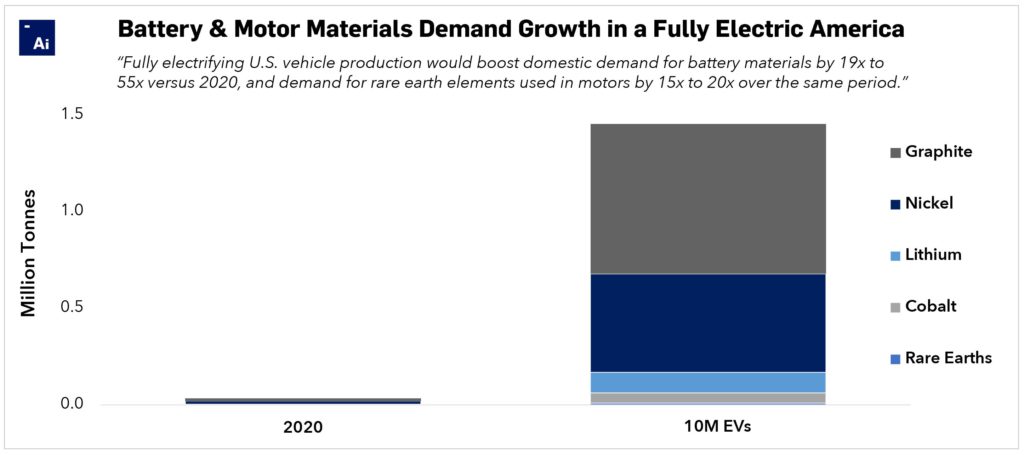

“Should these investments realize more manufacturing capacity, we’re looking at annual US EV sales of about 10 million vehicles by 2035. We crunched some numbers recently, and that reality in the US would increase domestic consumption of rare earth magnets by 15 times versus last year. It would increase domestic consumption of graphite by 55 times and all of the other materials somewhere in between,” says Castilloux.

Despite the robust demand growth, Castilloux says the market is not yet seeing the supply growth materialize to meet this growing demand.

“I think it’s broadly recognized that the supply side in the West is the better part of a decade behind in beginning to develop and in moving future production towards getting shovels in the ground. I think it is alarming to anybody that recognizes how fast demand is now growing and just how slow supply is adjusting to accommodate that,” says Castilloux.

According to Adamas data, on the electric vehicle (EV) registration side, across all three types — battery electric vehicles, plug-in hybrid electric vehicles and just simple hybrid electric vehicles — total global sales through the first five months are up more than 110% versus the prior year.

The number of gigawatt hours deployed into those vehicles has increased by more than 150% year-over-year.

Credit: Adamas Intelligence

“So not only are we seeing many more EVs selling than in the year prior, but we also see EVs with higher average battery capacity, which in turn translates into greater consumption of metals and materials for EVs,” says Castilloux.

“On the material side, we see over a 150% increase year over year in lithium demand through the first five months of this year. And with nickel and cobalt, both are up 115% year over year. Seeing growth rates of nearly 200% is just amazing.”

Castilloux guides for large deficits in lithium supply opening up before the end of this decade and extending to battery-grade nickel, cobalt, and some of the other materials like manganese, copper, and aluminium.

“So that will ultimately stunt the strategies of Europe, China and America, which at present all seem to be moving towards the desired future in 2035, where their nations are only producing battery-electric and plug-in hybrid electric vehicles. That simply seems implausible at the rate of current resource development,” says Castilloux.

Complicating new tech metal developments is the advent of ESG [environment, social, governance] investment principles over the past decade.

For instance, the reality that only certain types of class one nickel are amenable to use in batteries is now becoming even more specific, whereby it’s not good enough to simply have class one nickel; end-users and investors into the supply chains also want to check off a variety of ESG related characteristics.

“They want transparency into where that supply is being derived from. They want a good understanding of what the carbon footprint of that supply looks like. So, a lot more considerations coming into the pipeline, which will just add more layers of complexity to a supply chain that would struggle to keep up even if those considerations were not on the table,” says Castilloux.

Chris Berry, president of House Mountain Partners and an analyst who focuses on energy metals supply chains, says it’s obvious the world will be using a lot more of these tech metals in 2030 relative to today, and that underpins his current investment thesis.

He calls it ‘the paradox of green growth.’ “You have this huge push from governments and companies around ESG. There’s a buzz, if you will, of capital, looking to be deployed in the wake of Covid,” he tells The Northern Miner.

“The paradox is it’s going to take more raw materials to achieve those decarbonization goals as opposed to less. So, if we are extracting and refining more raw materials, you’ve got to find ways to do it that are more cost-effective and have a minimal carbon footprint relative to the traditional ways of doing business,” says Berry.

He stresses a challenging path [in this case, tech metals supply growth] will lead to innovation. “We are going to go from 350,000 to 370,000 tonnes of lithium demand today to a million tonnes by 2025. And then I would argue two million tonnes by 2030. The existing sort of known processes for mining and refining lithium isn’t going to work. They’re not going to be sustainable.”

Changing the rules usually forces companies to innovate. And the innovation is where the returns are generated, according to Berry.

“I think the way to be rewarded as an investor is finding those companies that have the large scalable assets with the right boxes ticked. But also, I think that, in terms of generating returns, you’re going to have to think about different technologies that go hand in hand, whether or not it’s with resource extraction or recycling,” says Berry.

In the past, cost was the prime determining factor for whether somebody wanted to buy a technology metal. The reality has now morphed into additional layers that add value to specific end-users.

That may make users more willing to perhaps pay a premium for Canadian sourced nickel, given the provenance and the transparency it comes with, versus something coming from Indonesia where there are more significant environmental footprints involved. “So that’s a plus for resource developers that formerly only had to compete on cost, but now can compete on cost and also on some of these other factors,” says Castilloux.

Both analysts don’t think it is too late for the West to catch up with China to establish new supply chains.

“I certainly don’t think it’s too late. And the reason being is that there is ample demand growth to go around looking forward. Even China alone will not be able to supply all of the world’s needs, likely before the end of this decade in the case of rare earths and for other materials as well. There’s certainly an opportunity for other producers, other nations to build up supply chains to capitalize on that strong demand growth. But there’s no doubt that they are years, if not decades or so, behind China. It will take them a long time to catch up volume-wise, on intellectual property and know-how,” says Castilloux.

Berry agrees that it’s not too late. “We’re getting there. We’re starting. I think, at least here in North America, under President Trump, this whole idea of critical metals and supply chains was couched in the notion of national security. And now, under a Biden administration, it’s couched under climate change and climate change, in turn, as national security.

“There is kind of a blurring of the line between national security and economic security. And I think that works really well for securing domestic or even regional supplies of critical metals,” says Berry.

Castilloux adds a final point that it’s wrong to think about the suite of tech metals as each living in its own silo. The reality is they’re all intertwined. For example, it’s easy to think about an EV’s motor and the battery as isolated from one another from a rare earths perspective. “However, if we can’t use rare earth permanent magnet traction motors, which are the most efficient traction motor available, the industry needs to substitute with an induction motor or some other alternative type that will consume more of the battery’s power to do one kilometre of work,” says Castilloux.

“That means they’ll need to increase their battery capacity even further, consuming more minerals to compete with other vehicle makers, or at least, to continue delivering on that driving range promised up until then. So, all of these materials really need to come up in harmony,” says Castilloux.

Be the first to comment on "Forecasts morph into reality as tech metals fundamentals heat up"