When Aurora Geosciences was contracted to manage the exploration program at Kennady Diamonds’ (TSXV: KDI) Kennady North project in the Northwest Territories in 2012, there weren’t any clues that the project would turn out to be as successful — or unusual — as it has.

“I think the only thing we felt is that the Kennady North project hadn’t been systematically tested,” said Aurora president Gary Vivian.

The project, revived by Mountain Province Diamonds (TSX: MPV; NASDAQ: MDM) in 2011, was originally part of the AK joint venture with De Beers that held the Gahcho Kué project (now in construction).

While two diamondiferous kimberlites, Faraday and Kelvin, had been discovered on the claims in 1999-2000, they were thought to be small “blows” along a dyke system and therefore of limited size potential. The project, 280 km northeast of Yellowknife, hadn’t seen any significant exploration since 2004.

Aurora started drilling at Kennady Lake in 2012, but it wasn’t until 2013 that pyroclastic kimberlite was recovered in drill core.

“All of the previous drilling had suggested that these were coherent kimberlites, which suggests they’re hypabyssal or dyke-like bodies,” Vivian said. “It’s the pyroclastic kimberlite that told us that the body is probably much bigger than was originally thought and would suggest that this thing has actually vented to surface. It opened our eyes to the possibility that this thing could be much bigger.”

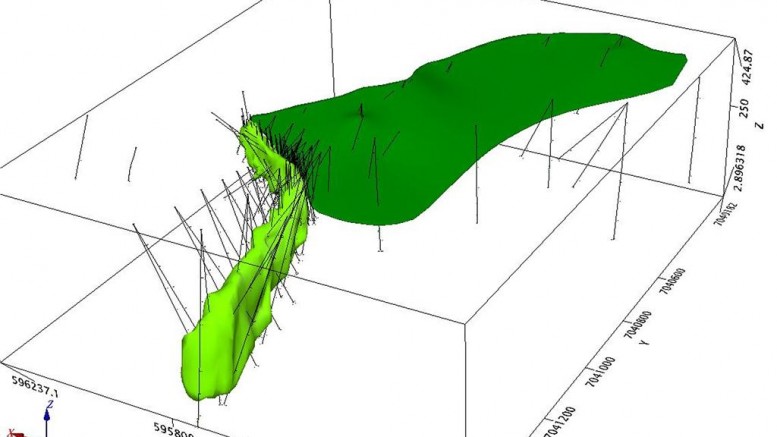

Since then, Aurora has outlined a very unusual kimberlite body at Kelvin. It’s not a dyke, or a classically carrot-shaped vertical kimberlite pipe, but a horizontal, boomerang-shaped, pipe-like body.

“This is a very irregular-shaped type kimberlite complex that hasn’t been recognized before,” Vivian says. “If you took a vertical pipe like the most classic kimberlites, and you tip that on its side, that’s almost exactly what the Kelvin body looks like.”

The kimberlite is about 600 metres long, between 75 and 200 metres thick (it thickens to the north), and 30 to 60 metres wide. It’s still open to the northwest.

On its south end, Kelvin surfaces beneath a shallow lake and is connected to the diamondiferous Kelvin sheet complex, which averages 8-10 metres thick.

Drilling at Faraday, 3 km northeast of Kelvin, has also returned pyroclastic kimberlite. There are four targets at Faraday that may or may not be connected, but so far the Faraday 2 target has been defined across a strike length of 130 metres, and appears to be a pipelike body.

The project also hosts the Doyle and MZ kimberlites and more than 40 targets.

Maiden resource

Without grade, Kelvin might be little more than a geological curiosity. However, sample grades to date have been very promising.

Samples taken from Kelvin in 2013 and 2014 and totalling 53.2 tonnes returned 124.9 carats of commercial-sized diamonds for a sample grade of 2.37 carats per tonne. A smaller 1-tonne sample from Faraday returned 4.76 carats of commercial-sized diamonds for a grade of 4.54 carats per tonne.

Early this year, Kennady reported results from the south lobe of Kelvin and from the Kelvin sheet: a 1.8-tonne sample from Kelvin’s south lobe returned 6.68 carats of commercial-sized stones for a grade of 3.64 carats per tonne, while a 47-kg sample from the Kelvin sheet returned 0.28 carats of commercial-sized diamonds for a grade of 5.95 carats per tonne.

A 436-tonne bulk sample taken by reverse-circulation drilling from Kelvin early this year will be used to compile a maiden resource in the third quarter, followed by a preliminary economic assessment. The bulk sample is expected to deliver a parcel of 1,000 carats for an initial valuation.

Kennady is targeting a 9-12 million tonne resource grading 2 to 2.5 carats per tonne.

It also plans to conduct another 20,000 metres of drilling this year.

While the Kelvin kimberlite is unusual, Vivian says it’s amenable to open-pit mining as it’s neither terribly deep nor large. At the south end, Kelvin comes to surface at the bottom of a shallow lake, and the bottom of the Kelvin body is only 70 metres below surface. Towards the north, the body starts about 200 metres below surface and extends to 450 metres depth.

“Three-quarters of the Kelvin pipe could be taken with a pit that’s about 250-300 metres deep and probably only 300-400 metres across.” Vivian says.

Perhaps the most exciting thing about Kennady North is that it implies much more potential to find more unusual kimberlites with economic potential in Canada’s North.

“I give Kennady a lot of credit for recognizing there was still potential left on the original AK claims,” Vivian said. “(Kennady CEO) Patrick Evans has proven that one or two passes don’t necessarily provide you with all the answers. Ideas and technology change.”

Be the first to comment on "Is Kennady North one of a kind?"