Stockholm, Sweden — As a result of acquiring the Zinkgruvan mine in central Sweden from

Known as South Atlantic Ventures until a recent name change, the company purchased the Zinkgruvan mine for US$100 million in cash plus payments for working capital and a US$1-million non-refundable deposit. Lundin Mining also agreed to pay Rio Tinto a maximum of US$5 million in price participation payments, based on the performance of zinc, lead and silver prices for a period of up to two years.

An economic analysis of the Zinkgruvan operation up to 2018 shows an accumulated after-tax net cash flow of US$209 million. The after-tax net present value at a 10% discount is US$103.5 million.

Rio Tinto became the owner of the mine when it purchased North Ltd. of Australia in 2000. North had purchased the mine from Union Minire (now Umicore) in 1995.

Lundin’s Zinkgruvan property, which is 175 km west-southwest of Stockholm, comprises four blocks covering some 6.8 sq. km. Two of these blocks are mining concessions and two are exploration permits. Also in the area, about 35 km east of the mine, is the Marketorp concession, where exploration of the historic zinc and lead showings is planned.

The Zinkgruvan property is on gently rolling hills 175 metres above sea level. There is little outcrop. Excellent road and rail access to the mine is available. Although Sweden sits at about the same latitude as Greenland, its climate is mild by comparison, owing to the Gulf Stream in the Atlantic.

Attracted to Sweden by its great climate and political stability, the company, led by mining and oil magnate Adolph Lundin, a Swedish native, appears to have picked up its ground at a great time, during lower prices for metals that have begun to turn up dramatically in the past six months. Through the years, the founders of the Lundin Group have amassed expertise in the mining and oil exploration sectors in almost every corner of the world, including some areas of high political risk. Not so in the case of Sweden, which is about as stable as countries come.

The Swedish Minerals Act was revised in 1992 and later changed to encourage foreign participation in the mining industry. Having a registered Swedish office in the country is required, and apart from a 28% corporate tax rate, there are no mining taxes or royalties.

The land owners in an area undergoing an application for a mining licence have the right to object to the granting of a permit.

One of the largest underground mines in Europe, Zinkgruvan, which translates simply as “zinc mine,” has been producing zinc, lead and silver since 1857. Back then, the Belgians were called in for their zinc mining expertise, but they ran into technical problems in smelting the sulphide ores. These problems were solved when, in 1864, a roaster was added in the nearby town of Ammeberg, on Lake Vattern. From the port there, the ore and concentrate was shipped to Belgium.

New shaft

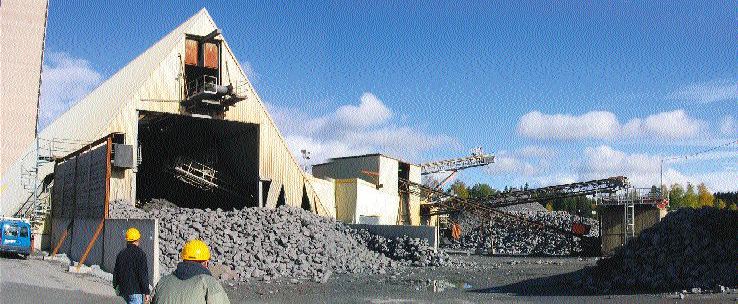

Production was stepped up in the mid-1970s, when a new main shaft was sunk to gain access to more ore, and heavy equipment was brought in. The mine’s main operation was down in Ammeberg until 1976, when a concentrator and tailings disposal facilities were built adjacent to the mine.

By 1982, the mine was cranking out 600,000 tonnes per year, which has been gradually upped to the current 800,000 tonnes. Production averaged 739,000 tonnes per year at grades of 9.3% zinc, 3.9% lead, and 90 grams silver from 1998 to 2003.

The mine has produced just under 30 million tonnes grading 11.3% zinc and 2.4% lead over its life. The silver production was not recorded until 1980. The mine produced 145 million lbs. zinc, 70 million lbs. lead, and 1.8 million oz. silver last year.

The run-of-mine ore is ground in a large autogenous mill, and the sulphides are floated in bulk, which is followed by lead-zinc separation. The mill has been built to handle 900,000 tonnes a year, though that production rate has never been reached.

The deepest ramp is 1 km, and the mill was modified in 1998. The PII shaft at the mine is the main one, whereas the PI shaft is mainly used for staff and equipment. Ore is mined by means of primary and secondary stoping, drifting and crosscutting. Afterwards, mined-out areas are filled in with tailings and cement.

The population of Zinkgruvan village is 450. A school was recently closed because too few students were available. The mine has 285 employees, a third of whom live in Zinkgruvan, with the remainder split between two other small nearby villages. Some 160,000 tonnes of lead and zinc concentrate are trucked all the way from the mill by road. Each truck carries 36 tonnes.

The mine is expected to produce for 19 years, based on current resources and reserves of lead and zinc, yet the company believes there is significant potential for expansion.

Situated in the Proterozoic-aged Bergslagen greenstone belt, the Zinkgruvan mine is 200 km south of the historic Falun deposit, which produced for nearly 10 centuries, from 1000 until 1992. The Bergslagen belt hosts iron ore and base metals mines. On the other side of the lake, near Zinkgruvan, cobalt was mined historically.

“Copper coins dating back to Roman times, found in London, have been traced back to central Sweden,” says Karl-Axel Waplan, executive vice-president of operations.

The deposit is situated in an east-west-striking synclinal structure comprising metavolcanics and metasediments. Intrusions, including gabbros and granites, resulted in the formation of granite aplites and a large number of pegmatites.

The Zinkgruvan deposit falls somewhere between the volcanogenic and sedimentary-exhalative models. Evidence of the former is the copper-rich stringer zone. Three main rock types at the mine have been categorized as metavolcanics, metasediments and a metavolanic-sedimentary group, and it is the latter that carries most of the mineralization.

The massive sulphides are associated with carbonates and cherts and extend over 5 km along strike. The deposit has undergone several phases of folding, and the northweast-trending Knalla fault has displaced the deposit, separating it into the Nygruvan and Burkland ore zones.

The dominant sulphide minerals are sphalerite and galena — generally massive, well-banded and stratifom, and from 5 to 25 metres thick. Chalcopyrite is present in minor amounts, as are pyrrhotite, pyrite and arsenopyrite (less than 1% each). Native silver has been mobilized into structures. The lead and zinc grades appear to increase toward the hangingwall of the massive-sulphide horizon.

Proven and probable reserves stand at 9.5 million tonnes grading 9.8% zinc, 4.8% lead and 97 grams silver per tonne. The total measured, indicated and inferred figure is 10.4 million tonnes averaging 9.7% zinc, 3.9% lead and 94 grams silver.

Indicated resources total 2.1 million tonnes grading 8.6% zinc, 2.4% lead, and 58 grams silver in the indicated category. In the inferred category are 8.3 million tonnes grading 10% zinc, 4.3% lead and 103 grams silver. The resources are exclusive of reserves, and the reserve figures include estimated mining dilution and are exclusive of stope pillars.

Based on previous success in this area, the company expects to be able to replace mineral reserves. The mine plan extends beyond 2022.

In addition to the lead-zinc and silver traditionally mined at Zinkgruvan, a copper resource was discovered in 1997 in the Knallagruvan area of the mine. The copper occurs in a marble unit on the hangingwall of the Burkland zinc and lead deposit.

The copper resources consist of 2.7 million tonnes grading 3% copper, 0.5% zinc and 52 grams silver in the indicated category and 850,000 tonnes of 3.3% copper, 0.2% zinc and 41 grams silver inferred.

With copper prices at the current level of US$1.30 per lb., mining is looking attractive. The company is working on adjusting the environmental permit for

the mine to process 500,000 tonnes of ore per year from the zone, along with continued zinc and lead production.

Lower costs

While Zinkgruvan’s cash costs are relatively low compared with other such operations, the weakening of the U.S. dollar does not help matters. The mine and the concentrator have the capability of increasing production, which would bring costs down further.

The Zinkgruvan mine has been operating for more than 100 years and has no significant environmental liabilities; that’s because the tailings do not generate acid and because modern containment is in place. In fact, one former tailings area has been fashioned into an 18-hole golf course with residences built along the course.

The lake that supplies the mill water for processing is cleaner after going through the mill.

The depressed state of the metals industry (that is, until recently) has meant that little effort has gone into exploration. But this year, the company is expected to have drilled 15,800 metres in more than 100 holes.

Exploration has been focused on the Norrbotten property in northern Sweden, where drilling has been testing the extent of copper-gold mineralization. Most of the holes drilled on the Rakkurijarvi discovery, an iron-oxide copper-gold zone, returned significant intersections. In particular, hole 023 cut 48.5 metres grading 1.07 copper and 0.27 gram gold per tonne at a down-hole depth of 75.5 metres.

The company also has a 38% interest in Stockholm-listed

Taking into account production from the Storliden mine, the company was expecting to produce more than 170 million lbs. zinc and 10 million lbs. copper in 2004. However, a production shortfall during the second quarter, and likely the third, was reported for Zinkgruvan. The problem can be traced to a rockfall, which forced one of the transport shafts to stop operating.

Be the first to comment on "Lundin celebrates Swedish homecoming"