VANCOUVER — The greenstone belt that hosts the nickel-copper-platinum group metal (PGM) and chromite deposits in northern Ontario’s Ring of Fire camp, 540 km northeast of Thunder Bay, is unique compared to other regions in Canada, says Noront Resources’ (TSXV: NOT) president and CEO Alan Coutts.

“In our case we have a typical greenstone belt, but we also have this large, layered ultramafic intrusion complex and iron formations abutting it. So it had all the right things going on to create the diversity of deposits we see there today,” he tells The Northern Miner in an interview.

Coutts says the similar belts elsewhere in Ontario and Quebec are less known for their magmatic copper-nickel, PGM and chromium deposits, which include examples such as Balmoral Resources’ Grasset copper-cobalt-PGM deposit in northern Quebec, the Raglan nickel-copper-PGM belt in northernmost Quebec, and some in Ontario’s Timmins district.

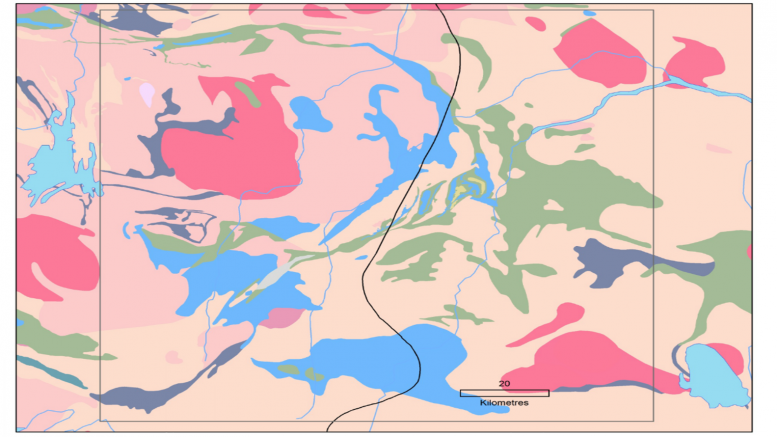

Simplified geology and mineral occurrences of Ontario. Credit: Ontario Ministry of Northern Development and Mines.

He says the age of the greenstone belts plays a role in the genesis of the magmatic-style deposits.

During the Archean eon, 4 billion to 2.5 billion years ago, temperatures on earth were still hot enough to drive deep-seated, high-magnesium melts — otherwise known as “ultramafics” — into higher levels of the earth’s crust without cooling rapidly, as they might today.

These melts, which contained a high amount of dissolved metals, would devour sulphur-rich country rocks during their ascent. Once sulphur was saturated in the melt, it would separate out of the magma — much like oil does in water — and absorb the dissolved metals.

Regional magnetic data outlining northern Ontario’s Ring of Fire metal district. Credit: Ontario Ministry of Northern Development and Mines.

When the magma flow slowed, the droplets of sulphur containing the heaviest metals would settle onto the base of the intrusion or flow, and then cool to form layers of massive sulphides, whereas the drops that weren’t heavy or large enough to sink before the magma crystallized ended up cooling in place.

Magmatic-style deposits often have horizons of massive sulphides that grade upwards into less dense, net-textured sulphides before ending in a horizon of disseminated sulphides.

Coutts points out that later deformation can tilt and truncate the rock package, whereas metamorphism or later-stage hydrothermal fluids can remobilize the sulphides into different parts of the crust.

In the Ring of Fire, the prospective ultramafic rocks are buried under lakes, bogs and younger rocks, making them hard for explorers to find. But in regional geophysical data, they pop out as a distinct, horseshoe-shaped magnetic anomaly that runs 60 km in diametre along the margin of a large granitic batholith.

The resource industry became interested in the region in 2002, shortly after De Beers drilled into volcanogenic massive sulphide (VMS) mineralization near McFaulds Lake while testing magnetic anomalies for suspected kimberlite material.

By 2003, exploration had outlined six more VMS deposits, but the first staking rush in the region began in 2007, after Noront discovered nickel-copper-platinum-palladium mineralization at its flagship Eagle’s Nest deposit.

Simplified geology and location of deposits in northern Ontario’s Ring of Fire metal district. Credit: Mungall et al.

In 2008, three high-grade chromite ore zones — Blackbird, Black Thor and Big Daddy — were discovered along a 14 km long strike length from Eagle’s Nest.

The deposits occur within different parts of the regionally trending ultramafic package.

At Eagle’s Nest, mineralization occurs as a pipe-like body 200 metres in width and up to several tens of metres thick, and at least 1.7 km deep, within a north-trending, sub-vertical komatiitic dyke. (Komatiites are a type of ultramafic rock.)

The deposit hosts proven and probable reserves of 11.1 million tonnes of 1.7% nickel, 0.9% copper, 0.89 gram platinum per tonne, 3.09 grams palladium per tonne and 0.18 gram gold per tonne. Inferred resources stand at 9 million tonnes of 1.1% nickel, 1.14% copper, 1.16 grams platinum, 3.49 grams palladium and 0.3 gram gold.

A welder working at Noront Resources’ Esker exploration camp in Ontario’s Ring of Fire region. Credit: Noront Resources.

In contrast, the nearby chromite deposits occur as flat-lying bodies, formed where the melt, rising as a plume from dykes below, pooled horizontally into a sedimentary package of banded ironstones. According to Noront’s technical report, the ironstones may have supplied the magma with enough sulphur to trigger precipitation of the metals.

Total chromite resources in the Ring of Fire have been pegged at 343 million tonnes, ranging from 23% to 38% chromium oxide, assuming a cut-off between 20% and 30% chromium oxide.

Noront has consolidated control over 75% of the staked claims in the region, and Coutts believes exploration in the Ring of Fire is still in its early stages.

“I’ve worked in a lot of nickel-copper districts during my career — Western Australia, Raglan, Sudbury basin — and usually these magmatic nickel-copper deposits occur in clusters,” he says. “So we’re pretty excited to explore there because we expect more than one deposit.”

He also sees potential for the region to host more orogenic gold and VMS deposits similar to ones found elsewhere in Ontario and Quebec.

For more on the topic, read, “The geology behind Ontario’s world-class metal deposits,” (T.N.M., Sept. 19-25/16) and “The geology behind Quebec’s world-class metal deposits,” (T.N.M., Sept. 26-30/16).

Be the first to comment on "Noront sheds light on Ring of Fire’s untapped potential"