Strolling around PDAC in March, I ended up in the core shack, perusing all of the world class, upper quartile tier 1 discoveries guaranteed to become a mine one day. Tucked away at one end was Barrick Gold‘s (TSX: ABX; NYSE: GOLD) giant Reko Diq porphyry project in western Pakistan. The photos of the parched Baluchistan desert took me back to 1997 when I spent a couple of months there, prospecting for similar systems along the Afghan border. A year later in 1998, I was involved in planning the second phase of drilling at Anglo American‘s (LSE: AAL) Zarshuran gold project in northern Iran and we sourced our drill rigs from Reko Diq, then owned by BHP (NYSE: BHP; LSE: BHP; ASX: BHP). The first Zarshuran drill program in 1996 was a slow grinding headache, (See Part 1) with only seven holes completed in three months. We couldn’t come to any firm conclusions about the project, so we started planning a follow up program for the summer of 1998.

We’d learned some tough lessons in Phase 1, and this time around we were going to be smarter. No more Iranian contractors. We’d use a modern, western-owned, truck mounted top-drive rig with 1,500-ft. capacity to drill the project. Hopefully we’d get to a technical go/no-go decision ahead of the complex legal work needed for a major mining investment in Iran. But multipurpose rigs didn’t exist in Iran, so we needed to find a western drill company ballsy enough to send one — along with experienced drillers — to Iran. Luckily, an Australian drill company — I’ll call them OzCo — had a suitable rig across the border in Pakistan at Reko Diq. The rig had finished its contract and OzCo wanted it earning revenue rather than sitting idle. OzCo’s drillers in Pakistan serviced the rig, stuck the rods and assorted widgets into shipping containers, loaded them onto flat beds and got ready to mobiliZe into Iran. All we had to do was drive it across the border at Taftan, fill in a few Iranian customs forms, and then drive it 1,900 km cross country to northern Iran. Simple.

And then everything stopped. OzCo called to say their gear was stuck at Reko Diq. The government had shut down western Baluchistan. Nothing was allowed on the main road across the province as a state of lockdown was imposed which dragged on for weeks. On May 28, all hell broke loose. The Pakistani government conducted five underground nuclear tests on top of a mountain in the Chagai hills just up the road from Reko Diq. Our rigs were stuck because of a nuclear test; something they never mention in corporate risk management classes.

Our convoy finally crossed the border mid-year under Iranian customs bond, and we were instructed to deliver everything to a customs yard in Tehran for inspection. There were dozens of police check points along the way, on the main roads into every town or city and random ones in the middle of nowhere, and every one of them wanted to stop my drill rigs to get a ‘”closer look at the paperwork” (read: shakedown for some cash) so the trip took weeks. At one point the convoy ground to a complete halt for four to five days in the middle of the desert. The roadblock cops were trying to watch Iran’s games in the world cup on an old black and white TV. Our logistics manager was sleeping under the drill rig truck in the desert heat by the side of a busy truck route nursing a bad case of piles, which he told me about in a tearful phone call to my hotel in Tehran one night. The cops were desperate for a new TV to watch the games and had randomly stopped dozens of trucks —all parked up in the wind-blown furnace — to see which driver would crack first and buy them a shiny new set as a bribe to get going again. One duly arrived out of a dust storm one day and the trucks all moved on to the next check point. Rinse and repeat. I was holed up in a hotel in Tehran with four very unhappy OzCo drillers including a large Fijian chap who’d taken to punching holes in his bathroom wall. They’d been there for seven weeks, no booze, no clubs, no women; nothing to do but wait for their equipment to arrive at site. Eventually the rigs and containers arrived at Zarshuran, but a lot of stuff was gone —stolen while it sat in the customs yard in Tehran. Some vital parts had been removed from the rig’s diesel motor which now wouldn’t start and we faced more delays as replacement parts were sourced in Tehran and shipped to site.

When drilling finally kicked off I was presented with a new problem; the imported drillers really didn’t like each other. Two were experienced and two were on their first job as fully fledged drillers. The new boys were given the night shift by the drill manager, which ordinarily wouldn’t be too much of an issue, but hostility was quietly brewing away between the two factions. It came to a head one night when a local villager — working as an offsider — was nearly killed in what should’ve been a preventable accident but the day shift saw no reason why they should discuss any issues they might have faced on the day shift with the night shift crew. Apparently, they weren’t there to teach them how to drill. So, when they did have a serious equipment issue one shift — the thread failed on locally made PQ drill rods when they were under torque — they said nothing. The thread had failed at the top of the hole at the connection between two rods, tearing them apart. The upper rod, which was connected to the top drive, broke off and whipped around at high speed, narrowly missing the driller.

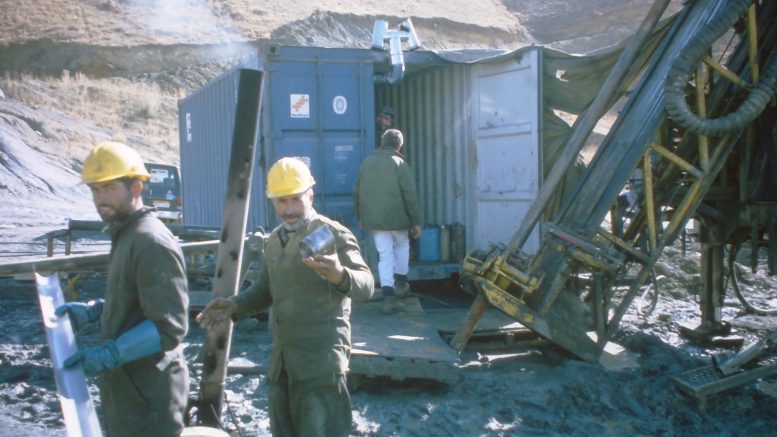

After the drilling accident: PQ rod with failed thread hanging to one side of the derrick. Credit: Ralph Rushton

Unfortunately, the same thing happened that night, but the night shift hadn’t been briefed by their colleagues on the potential issue. This time around, we weren’t so lucky. The PQ rod — 3 metres long and weighing close to 100 lb. — broke off under almost full torque, spun around at high speed and hit the offsider diagonally across his chest crushing him against the drill derrick. He was slammed against the hefty stilson wrench on the derrick which ruptured one of his kidneys, critically injuring him.

Safely tucked away in my little camp office plugging in logging sheets to my laptop, I heard all sorts of anguished shouting drifting across the valley from where the rig was. I jumped into my truck and when I got to the rig, the offsider was unconscious and having seizures with bloody foam coming out of his mouth. He had to go to hospital immediately — preferably to Tehran which was six hours away — or he might die; it wasn’t clear to us how bad he was hurt, but bloody foam at the mouth is never a good thing. The ambulance service in rural Iran is unreliable at best, so my Iranian colleague, Peyman, picked him up and stuck him in a truck and drove off at high speed to the local hospital. He was subsequently transferred to a specialist clinic in Tehran and spent weeks recovering from kidney damage.

That night I had a very panicked Australian driller in my office crying his eyes out. He was in mild shock from the accident and had convinced himself that he was going to a) be hung for killing an Iranian or b) spend the next 30 years in an Iranian prison making friends with people he wouldn’t ordinarily spend time much quality with. He begged to be taken to the border with Turkey so he could walk over to “safety,” but this wasn’t a viable option — the border is heavily patrolled — so I called our country manager in Tehran for some urgent advice. He told us to stay put and called the local police in Takab to report the accident. And then we waited. And waited. I was expecting a police visit or a session with the local health and safety inspector, but nobody came. We’d taped off the rig, worked out what had happened, and I’d reported it back to head office in London.

My conclusion was that the fault lay with the day shift driller. When I examined the accident site, I’d found two other rods with torn thread tucked under a tarp. Mr. Dayshift admitted he’d had the same problem with the poor-quality local rods but “it wasn’t his job to tell the other guys because they were grown ups.” My first instinct was to have him thrown off site but bringing in a replacement would’ve taken weeks; time which we didn’t have with the mountain winter drawing near. He stayed.

After three days, the tape flapped pointlessly in the wind and the hours dragged by. Eventually our manager called back. The local cops and the local municipality couldn’t care less. They were surprised we’d even bothered calling them. “It’s God’s will” was literally the response from the police chief. “Why did you call? Nothing to do with us.”

In the end, we completed a couple of dozen core and RC holes. The geology was spectacular and the gold grades locally excellent although with orpiment in the orebody, the arsenic levels were high. The program was a qualified success, overshadowed by the accident, and we still didn’t have enough holes to properly evaluate the full strike length of the deposit. In early 1999 I was transferred to Anglo’s head office in London and spent the next three years raising two baby boys, compiling budgets and writing reports. Anglo finally abandoned Zarshuran — the Iranian government proved too hard to deal with — and it was put into production by a quasi-government mining company.

— Ralph Rushton is a geologist and has worked at mines and exploration projects around the world including stints in South Africa, Turkey, Bulgaria, Yemen, Iran and Pakistan. He is currently the president of Aftermath Silver, a silver development company with projects in Chile and Peru. In his spare time, he writes about mining and exploration for his popular blog, urbancrows.com.

Be the first to comment on "How not to drill a project, Part 2 — drill crew tensions lead to disaster"