That mines and mining projects get recycled from one company to the next isn’t new — it happens all the time.

What makes the Prairie Creek mine a little different is that Canadian Zinc (TSX: CZN; US-OTC: CZICF) picked up the permitted, fully built — and yet never operated — mine, for a song, thanks to the demise of the legendary Hunt brothers.

In 1966, the Texas-based siblings acquired the Prairie Creek property, 500 km west of Yellowknife in the Northwest Territories’ Mackenzie Mountain Range. They completed exploration and a feasibility study, built a road connecting the property to the Liard Highway, and then financed and built the mine and mill. But lower silver prices and bankruptcy proceedings intervened in 1983, derailing their plans just at the time they hoped to flip the switch.

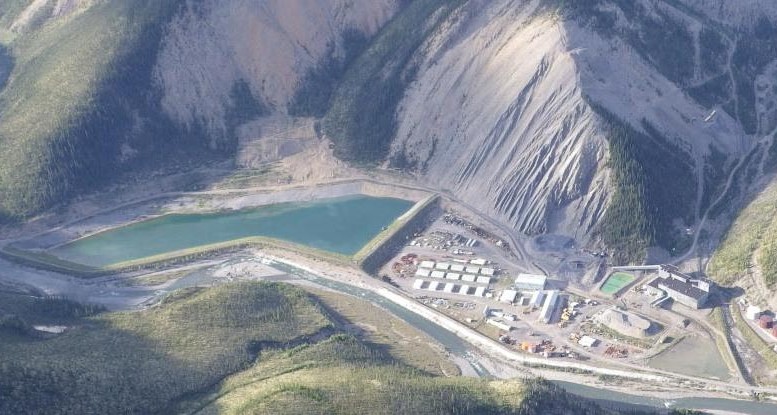

So when Canadian Zinc acquired the mine for $2 million in the early 1990s, the junior got a processing plant that was 90% finished, a 1.5-million-tonne capacity tailings impoundment, a power plant and a water-treatment plant.

“They invested $65 million [1982 dollars] and were just about to go into commissioning, but were tripped up in the U.S. by allegations that they were trying to manipulate the silver price,” Canadian Zinc’s vice-president of corporate development Steve Dawson says. “They were a few months away from being in production. So it just sat there, dormant. We’ve kept it on care and maintenance.”

Alan Taylor, the company’s vice-president of exploration and chief-operating officer, who has been involved with the project for more than 15 years, estimates that all of the infrastructure the Hunts left behind is probably worth more than $200 million in today’s dollars, such as the mill, the ancillary service buildings and the 5 km of adits that were dug into the orebody.

The portal to underground workings at Canadian Zinc’s Prairie Creek zinc-lead-silver project in the Northwest Territories. Credit: Canadian Zinc

Since acquiring Prairie Creek a quarter of a century ago, Canadian Zinc has been slowly but steadily drilling out the deposit and moving the project through six stages of permitting. It now has all the permits it needs to start production, except for one that it needs to upgrade the winter road for all-season use. The road connects the project to the Liard Highway, 170 km away. (The company submitted its application in April 2014, and it is now undergoing environmental assessment before the Mackenzie Valley Review Board.)

Indeed, if financing wasn’t an issue — as it is for most companies in the current downturn — Dawson and Taylor speculate that the company would be looking at a two-year timeline to production.

While raising money won’t be easy, Canadian Zinc’s management team is optimistic that a confluence of factors should open doors and wallets relatively soon. These factors include: an expected zinc deficit, off-take agreements the company has recently signed with Korea Zinc and Sweden’s Boliden, and a recent prefeasibility study that indicates positive economics over a 17-year mine life.

According to a prefeasibility study released on March 31, Prairie Creek should produce an average each year of 60,000 tonnes of zinc concentrate and 55,000 tonnes of lead concentrate, containing 86 million lb. zinc, 82 million lb. lead and 1.7 million oz. silver.

Using metal price forecasts of US$1 per lb. for both zinc and lead, and US$19 per oz. silver, the mine would yield average annual earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization of $90 million, the study says.

Preproduction capital costs would come in at $216 million. (Adding a $28-million contingency brings the total to $244 million.) Payback would take three years, given a post-tax net present value at an 8% discount rate of $302 million, and a 26.1% post-tax internal rate of return.

Sustaining capital over the mine is an expected $70 million, 90% of which would be incurred during the first five years relating mostly to mine development, as the operation expands to deeper levels, as well as to the remaining balance of capital lease payments.

The study is based on a measured and indicated resource of 8.7 million tonnes grading 136 grams silver per tonne, 8.9% lead and 9.5% zinc. (The project’s inferred resource, which stands at 7.1 million tonnes averaging 166 grams silver per tonne, 7.7% lead and 11.3% zinc, is not incorporated into the study.)

The mine would be an underground operation using long-hole stoping based primarily on mining the main quartz vein, with steady production of 1,350 tonnes per day.

Tailings from the mill would be placed permanently underground as paste backfill, produced in a new paste backfill plant.

Once the concentrates reach the Liard Highway, they would be trucked to the railhead at Fort Nelson and moved by rail to the port of Vancouver for shipment to overseas smelters.

The memorandums of understanding Canadian Zinc has already announced with Korea Zinc and Boliden represent all of the planned production of zinc concentrate and half of the planned production of lead concentrate for the first five years that Prairie Creek operates.

Korea Zinc, which owns and operates zinc smelters in South Korea and Australia (as well as a lead smelter, also in South Korea), will buy 20,000 to 30,000 wet tonnes of zinc sulphide concentrates a year, in addition to 15,000 to 20,000 wet tonnes of lead sulphide concentrates and 5,000 tonnes of lead oxide concentrates.

Boliden will buy a minimum of 20,000 dry tonnes and up to 40,000 dry tonnes of zinc sulphide concentrates a year for at least five years from the start of regular deliveries.

“The North is a challenging place to be because of a number of factors — such as the lack of infrastructure and the cost of carrying out work programs — but we believe we’re getting over a lot of these challenges, and we think that the North will benefit greatly from Prairie Creek,” Taylor says. “This project is near and dear to me, as I recognize it as a great opportunity — not just for the company, but for the whole region, which is in dire need of economic development.”

Be the first to comment on "Canadian Zinc pushes Prairie Creek"