SITE VISIT

Miguel Auza, Mexico — In the early 1920s, an American mining engineer named Robert Foster arrived here from the railhead at Catalina, 55 km away, on “a good road . . . in two-and-a-quarter hours in a Ford.”

Today the roads, and even the Fords, are better than they used to be. So are mining and exploration technology, which is why an old mining area around Miguel Auza may see renewed development on mineralization known to the conquistadors and the Aztecs.

The area around Miguel Auza had already seen four and a half centuries of mining before Silver Eagle Mines (SEG-T) got here. While the first written records of silver production go back to the Spanish colonizers in the 1560s, obviously indios knew about, and exploited, the area’s silver veins.

The town grew up over the mines, and there is known to have been active mining in the last half of the 19th century, with some ore being shipped directly to the American Smelting and Refining Co. — later Asarco — in Monterrey, and some being treated by the “patio” process, a primitive form of heap leaching and amalgamation.

Mining in those days did not extend below the water table, for two reasons: in those days before flotation, sulphide material could not be treated, and hand pumps and bailing buckets raised by mule teams were no match for the task of keeping the workings drained. But mineralization that persisted to depth was enough to cause the operators to bring in steam pumps to dewater workings they planned to take deeper.

That, however, was all before the 1910 insurrection that drove the dictator Porfirio Diaz from office. Foster’s 1921 report notes laconically that, but for four boilers, “all other machinery was destroyed during the Revolution.” After that, the mines languished, without access to capital and without any operator to take them on.

It was in 1966 that a local operator, Alejandro Gaitan, started to mine the old workings as a private venture. The ore was mostly hand-cobbed high grade, shipped to smelters, and Gaitan shut up shop in the early 1970s. A second private operator, Javier Martinez Lomas, built a small mill in the early 1980s, but packed up a few years later. Even so, Martinez, and Gaitan’s family, still retained ownership of the mining concessions.

That allowed Michael Neumann, a mining engineer born in Mexico to Canadian parents, and his business partner, electrical engineer Javier Aguirre Sanchez, to assemble a land package through claiming and through deals with the Gaitan and Martinez families. Neumann and Aguirre approached Neumann’s old friends from the Haileybury School of Mines, Terrence and Kenneth Byberg, with a property deal on Miguel Auza. The four formed a private company, AJ Resources, and they — and some patient private shareholders — spent the next couple of years working on the property using their own money. Breathing a long sigh of relief, they took the company public in May 2006.

Two projects

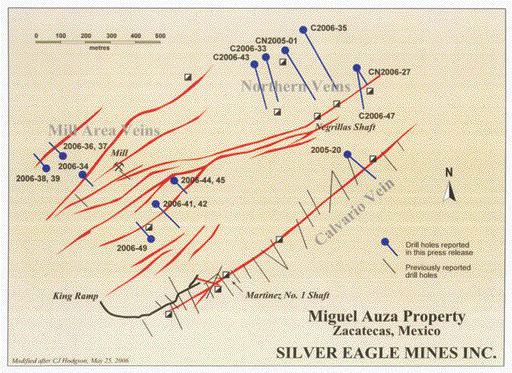

What has gone public is really two projects: development around the Martinez shafts, with the early goal of bulk sampling and the longer-term goal of production, and detailed exploration on other vein structures on the property that could establish a much larger resource.

While still working on private money, Silver Eagle began driving a decline to the old workings around one of Martinez’s old shafts. At the time of The Northern Miner’s visit, the ramp had joined up with Martinez’s No. 2 shaft, and Silver Eagle had developed two crosscuts, one to examine the northwest-striking Ramal vein and the other to intersect the northeast-striking Calvario vein. (It is now at 105 metres vertical depth.)

The two vein systems differ in more than just their orientation; the Ramal mineralization is principally oxide while the Calvario — which occupies a structure about 1,400 metres long — is sulphide-dominated, with less silver, more lead, and a lot more zinc. Both, however, cut the same host rocks — Cretaceous sandstones and shales, with some carbonates — and all belong to a swarm of structures at the southwest end of a dioritic or granodioritic intrusive body, probably of Tertiary age and probably shaped like a laccolith, intruding roughly parallel to the stratigraphy of the country rock, and domed at the top.

There are more than 20 mineralized structures known, but Calvario, three veins in the Ramal group, and four veins grouped about 1 km northeast of the ramp have seen the great bulk of historical underground production. Most of the veins strike a little east of northeast, roughly parallel to the long dimension of the diorite; Calvario is nearly vertical and most of the others have a shallow-to-moderate northwest dip.

The veins cut through both the sediments and the diorite, and inclusions of the diorite in vein material suggest the veins were formed in the later phases of the diorite’s emplacement.

Most of the veins are narrow, and — fitting their old-time history — very high-grade. Old records, where they exist, mention hundreds or thousands of grams of silver per tonne, along with lead and zinc over 10%. Sampling by Mexican government geologists while Martinez was operating the mine in the early 1980s turned up silver grades between 1,200 and 2,900 grams per tonne (35-85 oz. per ton).

So clearly what Silver Eagle is looking at here is not a large-tonnage model that will excite the Street and make it loom up as the next takeover target for a resource-hungry major. Rather, it is lining itself up for the modest but highly profitable production that is not hard to get to when a ramp has a portal at one end and a high-grade vein at the other. (And, to paraphrase Twain, no liars at either end.)

That fits with the modest resource estimate announced for the project so far: 186,000 tonnes indicated, all on the Calvario vein, at 243 grams silver per tonne with 2.53% lead and 2.86% zinc, plus 740,000 tonnes inferred, on Calvario, Ramal, and some other veins, grading 150 grams silver per tonne, 2.49% lead and 2.34% zinc. The resource estimate was based on 9,768 metres drilled in 2004 and 2005.

Silver Eagle has done 11,700 metres of drilling so far this year, some assessing the known vein system and some on exploration work. Drifting in the mine itself has found two new veins in the Ramal series, which will be part of a bulk sample.

The drill-indicated resources on the Calvario vein (180,000 tonnes) would be enough to feed the existing mill, rated for 100 tonnes per day but easily scaled up to handle 300 tonnes, for about a year and a half. That would allow immediate production, but management would rather not commit to that size of operation now, seeing the possibility that a larger mine and mill might be justified and wanting to develop it at the optimum rate right from the start.

“I don’t see this as a 300 (tonne)-a-day operation, but all this drilling we’re doing is going to tell us what it is,” says Terry Byberg, now chief executive officer of the company.

Another effort that will tell Silver Eagle what the project is has started underground, a bulk-sampling program that will use the rehabilitated mill. The plant is a simple crusher, a small ball mill and a set of flotation cells, but it can take 100 tonnes a day and could be scaled up to 300 tonnes if more throughput is needed. The refurbished mill is about 5% from completion.

At this stage 2,300 tonnes of material, from the Calvario and from three of the Ramal series of veins, is on surface. A milling campaign, slated to consume 30,000 tonnes from areas accessible from the ramp, will await the completion of a tailings dam a short distance from the mill.

Early metallurgical results from grab samples taken out of the Ramal 2 vein produced a concentrate grading 12,000 grams silver per tonne, which captured 81% of the silver in the sample. More test work is under way.

Project potential

The project’s other side is exploration potential over a large land package, about 275 sq. km that covers the area with the v

eins and a surrounding countryside with known mineral showings.

The Calvario vein has been extended to 1.4 km by drilling, and on its strike extension, dubbed the East Zone, there appear to be two parallel, previously unknown veins to the northwest of Calvario. The northernmost of the three carried 3,261 grams silver per tonne, 2.61% lead and 3.07% zinc over a core length of 2.05 metres; the middle vein ran 159 grams silver, 0.98% lead and 1.09% zinc over 0.85 metres, and the southernmost — the Calvario eastern extension — ran 933 grams silver, 2.02% lead and 1% zinc over 0.35 metre.

Exploration drilling in the Mill area, about 500 metres northwest of the ramp, has intersected silver grades mainly in the 40-gram to 100-gram-per-tonne range, with lead and zinc grades of a few per cent each, but some of the mineralized intersections have been relatively wide. One of 7.8 metres ran 68.8 grams silver, 1.74% lead and 1.61% zinc, with 0.36 gram gold per tonne; another drill hole cut 2.5 metres grading 32.5 grams silver and 1.7 grams gold per tonne, with 0.22% lead and 0.24% zinc.

It is to the northeast, where a handful of old shafts cluster around an intersecting system of veins, where Silver Eagle has drilled most of its high-grade intersections. Silver grades in the northern veins (Escondida, Esperanza, San Ramon and Union) have proved to be reliably above 100 grams per tonne and have gone as high as 7,600 grams.

The mineralized intersections can be narrow — some are down to 0.2 to 0.3 metre — but most fall between 0.5 and 1.5 metres, at grades that would allow a useful mining width. Among the better results came from an early hole that cut five separate mineralized zones, including one that graded 7,378 grams silver per tonne, plus 4.72% lead and 5.34% zinc, over 0.5 metre, and another that ran 318.5 grams silver per tonne (with minor base metal credits) over 2.4 metres.

There has been little “modern” systematic mineral exploration in the area, apart from a Mexican government geochemical survey, so Chris Hodgson, Silver Eagle’s geological consultant, thinks there may be considerable potential. He points to the Fresnillo mine, operated by Industrias Peoles (IPOAF-O, PENOLES-M), which was a small narrow-vein producer for years and was close to closure.

“Their last chance was to drill in the pediment,” south of the mine, says Hodgson, which they did without much geological control. What the geologists found, though, was a separate set of veins at an entirely different orientation from the ones Fresnillo had been mining. Fresnillo now produces 34 million oz. annually and trails only Cannington, in Australia, as the largest silver mine in the world; moreover, Cannington’s production profile is heading downward.

Bringing mining back to a town that hasn’t seen it for a generation is a delicate task. The most delicate part may be in managing expectations, and Byberg’s pleasure in getting the town behind the project is obvious.

“You take your time, do it right, and now we’re drilling in people’s backyards.”

Be the first to comment on "Silver Eagle heads to test mining at Miguel Auza"