Belo Horizonte, Brazil — Shovelled out of the verdant hills three centuries ago, or hoisted from modern-day mines, the gold of Minas Gerais is sprinkled through the history of Brazil. It made the kings of Portugal take notice of their new colony; it bankrolled the country’s first independence movement; it built the roads and railways that opened central Brazil for a vast mining and steelmaking industry.

And though that little brother grown big, the steel business, dwarfs gold mining in Minas today, the hills that ring Belo Horizonte still mark Brazil’s big-league gold country, the camp of Morro Velho, Raposos, and Cuiaba. It’s a camp that historically has been the preserve of the biggest miners —

A shared philosophy, perhaps: Toronto money-guys, a New Hampshire dealmaker, and the most senior graduates of Belo’s mining school of hard knocks have fashioned

It is less a lament than a fact of life that the biggest miners can’t build small mines: the task is as exacting as building a big mine, without putting big numbers on a big company’s earnings statement. Give the same project to a small or mid-tier company, though, and it can be an important asset or even a company-maker: the kind of operation Jaguar is hoping to build in the Quadrilatero Ferrifero, the mining district that centres on Belo.

The big boys, over the years, had built up an inventory of gold prospects in the Quadrilatero that didn’t fit a big company’s needs. Jaguar’s Brazilian management, led by Anglo’s former chief executive in Brazil, Juvenil Felix, saw the opportunity that a book full of dormant properties created. Felix and other Anglo alumni — former mining manager Adriano do Nascimento and ex-manager of the Crixas mine, Lucio Cardoso, among them — approached AngloGold, and later CVRD, with a proposal to take those properties over, mainly in relatively simple cash deals. The result is a significant landholding in the area, giving the company a presence to match its founders’ credibility.

Jaguar has assembled ground in four main areas of the Quadrilatero: Sabara, a short drive east of Belo Horizonte; Santa Barbara, a little farther to the east; Paciencia, an hour or so to the south of the city; and Turmalina, near Divinopolis farther to the west. Each of the properties has an identified gold resource, and Jaguar’s plan is basic enough: develop near-surface oxide resources to finance a longer-term plan to bring hard-rock gold deposits into production.

Another of its purchases is essential to the strategy — the Caete carbon-in-column gold plant, near Sabara, bought from CVRD when the big iron miner got out of the gold business. Caete, a small plant rated to process 1,000 tonnes per day, is now treating 1,500 tonnes per day from the small open pit at Sabara, and Jaguar produced its first 15,000 oz. gold in late 2004.

It wasn’t a smooth start, owing to unusually high rainfall and difficult conditions on narrow roads that have forced the Sabara operation to move ore in small contracted dumptrucks rather than large mine vehicles. Still, cash flow is cash flow, and the Caete mill is compensating for production difficulties at Sabara; and a higher gold price is paying for the long truck haul to Caete, which Jaguar management estimates to cost about US$50 per oz.

A second plant is being put together for Sabara, and is scheduled to go into production in the last half of the year.

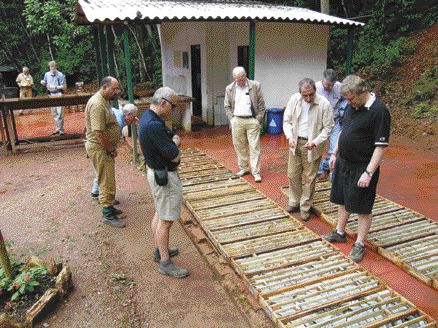

Mining at Sabara is not open-pit bulk mining; it’s selective mining in a small pit. At the time of The Northern Miner’s visit, one shovel was at work, mining a 1,100-tonne block that graded 2.5 grams per tonne. The stripping ratio is around 5, and dilution in the pit averages around 12%.

The deposit is hosted by a tuff and pelite sequence with overlying iron formation and chert. Like most of the gold deposits in the area, mineralization concentrates in the noses of folds. At Sabara, grades in the nose of the overturned anticline that hosts the mineralization rise to 10 grams per tonne, against a reserve grade in the pit of 2.6 grams.

A little east of Sabara are the Catita and Juca Vieira deposits, both with sulphide resources. Catita has a small (80,000-tonne) but relatively high-grade resource (7.8 grams per tonne). At Juca Vieira, sericitized low-angle shears in the volcanic and iron formation package host 654,000 tonnes grading 5.5 grams per tonne, with gold, arsenopyrite and quartz. “The deposits are totally open, laterally and at depth,” says Jaime Duchinni, Jaguar’s geological director. They are close enough together that they could be developed from the same ramp.

Building a plant at Sabara would free capacity at the Caete plant for oxide material from Santa Barbara, 33 km east of the plant, where pre-stripping had started at the time of the Miner’s visit.

Santa Barbara’s Pilar prospect could be the typical Jaguar project: an old CVRD holding, it has known oxide and sulphide resources that Jaguar is now evaluating for production. Pilar’s measured oxide resources amount to 429,000 tonnes at 3.4 grams gold per tonne, and a measured and indicated sulphide resource of 2.1 million tonnes at 6.5 grams has been drilled off by previous operators. The mineralization is in folded iron formation and greenschist, concentrated in the hinges of a fold — a typical geological setting for gold in the Quadrilatero.

Jaguar’s plan for the sulphide deposit at Pilar is to finish a feasibility study, and to go underground with a 1-km decline in 2006. Production could start in 2007.

For the hard-rock mines, processing capacity has been reserved at Anglo’s Queiroz carbon-in-leach plant east of Belo Horizonte, which can accommodate both free and refractory gold mineralization. Jaguar has contracted for 800 tonnes per day throughput in the Queiroz plant, and would also have use of a roaster for refractory material from Sabara and Turmalina.

Early hopes for sulphide production are pinned on Turmalina, where two resources have been blocked out. The South Zone holds a non-refractory gold resource of 1.6 million tonnes grading 5.9 grams per tonne, and the North Zone a refractory resource of 1.5 million tonnes at 5.7 grams. Both have additional inferred resources, mainly at depth. These resources are based on drilling to a limited depth, and some past development off a decline driven by Anglo, which had mined a small open pit with oxide mineralization when it owned Turmalina.

Turmalina is also a specimen of another characteristic of Quadrilatero gold deposits: they tend to go deep, and their tonnage potential is often not recognized until underground development has advanced several mining levels. “No significant projects have been found here by surface drilling alone,” says Jaguar director Robert Jackson.

Morro Velho, for example, was developed on 29 levels, to a depth of 2,453 metres. Almost all the orebodies in the camp are linear in form, with relatively shallow plunges. Eduardo Ladeira, a professor at the Federal University of Minas Gerais and a consultant to Jaguar, describes Morro Velho as “a banana,” plunging eastward and flattening at depth.

It is Turmalina’s depth potential that probably offers Jaguar more early chances at blue sky, based on the results of recent drilling between 300 and 350 metres vertical depth. Turmalina occupies a relatively wide structure, about 150 metres in strike length, and dips steeply to the northeast.

Gold grades in that part of the Turmalina structure ranged from a gram or two to 17 grams per tonne, and widths were slightly greater than at shallower depths. About 5,700 metres of additional drilling is planned, with three drills on the project.

Once it is establ

ished that developing the resource is feasible — a study that should be done by July — Jaguar will decide whether to use the contract milling at Queiroz or build its own 1,200-tonne-per-day mill at Turmalina.

Mining at Turmalina would be off the existing decline, probably by sublevel stoping or, if widths justified it, longhole stoping. Ground conditions are generally good, but a paste backfill plant is part of the study.

South of Belo Horizonte, at Paciencia, Jaguar has three more drills turning to assess mineralization at the Santa Isabel prospect. Another of Anglo’s small open pits, called Rainha, sits in a manmade valley on the Sao Vicente shear zone. The valley consists of pits dug by colonial-era slaves mining free gold from the weathered upper levels of the shear zone. “The most important part of the structure, we have,” says Duchinni.

Santa Isabel occupies a southeast-striking and northeast-dipping shear with mineralized shoots that rake southeast down the structure. Shoots on lower levels, exposed in an old Anglo decline, are clearly traceable to mineralized zones at surface, suggesting that the zones are consistent down-plunge.

Mineralization at Santa Isabel consists largely of free gold, some of it fairly coarse (sand-sized). Visible gold is common in the core, and grades are consequently quite irregular — in general they work out to 5 grams per tonne over widths around 15 metres.

Currently Jaguar has development and inital production at Paciencia slotted in between Turmalina and Santa Barbara. With Turmalina, it is the main focus of the company’s exploration and resource-drilling effort this year.

Surface rights have been purchased for a mill site and tailings pond, with a view to bringing Santa Isabel into production in 2007. With two satellite deposits, Bahu and Marzagao, Paciencia’s sulphide resource is about 5.9 million tonnes grading 4.4 grams per tonne.

None of these projects is huge, though taking them together Jaguar is forecasting production of 75,000 to 100,000 oz. in 2006, and 150,000 to 200,000 oz. the following year. Springing some small deposits from the scale trap could, if all goes well, add up to a profitable mid-tier producer.

Be the first to comment on "Springing the scale trap"