Salmo, B.C. — In its heyday in the 1950s, this forgotten mining camp in southeastern B.C. supplied the metals that laid the foundation stones for what became one of Canada’s leading gold producers, Placer Dome.

Before operations ceased in 1973, the Jersey Emerald claim, produced 1.6 million tonnes of tungsten ore, wealth-creating material that helped to turn Placer Dome into a metals giant before it was swallowed last year by Barrick Gold (ABX-T, ABX-N).

Now this century-old property in the hills above Salmo is getting a lift from global shortages of tungsten, a metal that is renowned for its durability, high melting point, and a range of applications that include light filaments and armour-piercing bullets.

The tungsten ore was extracted from a handful of deposits that are now controlled by Sultan Minerals (SUL-V, SLMLF-O), a Vancouver company that is hoping to take advantage of near-record prices by restarting production on its tree-lined property.

“If metal prices don’t collapse, I’d say it’s a go,” said Ed Lawrence, a 71-year-old mining industry consultant, who was mine manager when Placer made the decision to halt production 35 years ago.

At that time, tungsten prices had slumped to around US$50 per tonne, and a resource tax imposed by the governing B.C. New Democrats wiped out whatever profits Placer could hope to achieve by keeping the operation running.

Three decades later, Sultan is using Lawrence’s extensive knowledge of the 92-sq.-km Jersey Emerald site in a bid to prove up sufficient reserves of tungsten to support a production rate of about 2,000 tonnes per day.

Hopes that it will be feasible to restart the mine rest on a number of factors, which have combined to send tungsten prices soaring to a near-record high US$258 per tonne, from an average of around US$60 in the last decade.

They include export restrictions in China — a country that produces about 85% of the world’s mined tungsten — and a lack of exploration, which has left the Western world with only a handful of tungsten mines.

One of those, North American Tungsten’s (NTC-V, NATUF-O) Cantung mine in the Northwest Territories, could be exhausted within three years, potentially leaving Primary Metals (PMI-V, PMIZF-O) — owner of the Panasqueira mine in Portugal — as the Western world’s only publicly traded primary tungsten producer.

Aside from privately held mines in Russia and some mom-and-pop operations in Bolivia, Sultan would have few publicly traded competitors if it executes the plan to restart production on Jersey Emerald.

In an interview, Sultan president Art Troup said it would likely cost about $50 million to reopen the site, using contract miners. The cash flow, he said, could be used to continue exploring for other minerals, and outline reserves in a molybdenum deposit, which lies beneath the mine workings.

The type of mine that Sultan envisages would be fed to some extent by ore that remains from two lead-zinc mines and five former tungsten mines that supplied strategic metals to the United States during the Second World War.

Sultan’s optimism is based on a preliminary resource estimate issued by the company in November. It says drilling so far has outlined a 3.7-million-tonne resource, averaging between 0.37% and 4% tungsten oxide per tonne.

That resource is thought to lie within the workings of what used to be known as the Invincible and Dodger mines.

Based on results of 21 drill holes, the company has also outlined roughly 500,000 tonnes of indicated and inferred molybdenum resources in the Dodger workings.

When The Northern Miner toured the property recently there was little visible evidence that the mines on what is known as the Jersey Emerald property were a major source of tungsten or any other kind of metal.

That’s because Placer stripped the property of virtually all of its former contents, leaving only the processing plant foundations and an empty swimming pool. The pool was a popular venue for local residents because it was heated with water from the old mine compressors.

It remains a landmark that is visible from the dirt road leading up to the entrance of the underground workings of the Invincible mine.

East Emerald

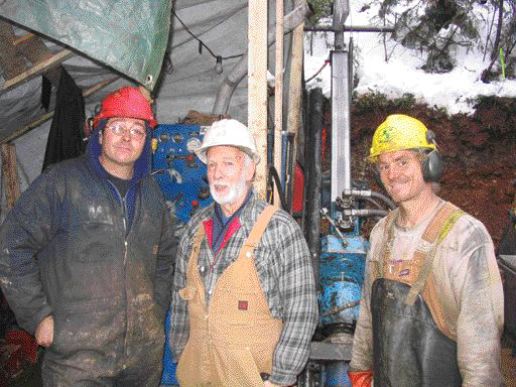

On a drive along the winding dirt roads during the recent visit, a drilling crew was trying to add to the known tungsten resource by probing in an area known as the East Emerald tungsten zone, which is located above the old Invincible mine.

Before taking a break for Christmas, the drill crew tested for downdip extensions at the western edge of the East Emerald zone, which has been traced for 1,100 metres along strike, and is accessible both from surface and from the Invincible mine underground workings.

Lawrence believes the East Emerald zone could be a vital part of a future mining operation because it has the potential, he said, to contain a large volume of ore that may be amenable to low-cost bulk mining and treatment methods. Having completed four holes recently, he promised “much more drilling” in the spring.

“In summary, what you can say is that this mountain is tungsten-bearing and contains a lot of tungsten,” Lawrence said. “It may be in a lot of small deposits, but they will all feed the same plant.”

Based on what he has seen so far, he is confident that production will resume sooner or later.

But whether that actually happens appears to depend on whether Sultan can get the financing to bring the mine back into production.

A member of the Lang group of companies, headed by 81-year-old financier Frank Lang, Sultan is hampered by the fact that it has 80 million shares outstanding that traded recently at 17 on the TSX Venture Exchange.

Troup said the company could generate some cash by processing an estimated 1 million tonnes of tungsten-bearing tailings that remain on the property, if it is possible to do so.

Moly Potential

Sultan also envisages producing a scheelite concentrate that would be sold to iron and steel makers for use as an alloy or to tungsten carbide producers. The company said European-based tungsten metal producers have expressed interest in taking concentrates from Jersey Emerald.

However, the capital cost of developing the molybdenum would be considerably higher and would likely require the participation of a partner with deep pockets.

Troup estimates that a molybdenum mine could cost around $400 million to bring into production.

“We are very excited about the molybdenum,” he said, adding that strong demand from the Chinese steel industry has sent prices rising to US$26 a lb. from US$5 in early 2004.

Producers benefit from the fact that there are few substitutes for molybdenum, which is widely used as an alloying element in the production of steel and cast iron.

However, optimism in the Iron Mountain camp is tempered by the view that the long-term outlook for molybdenum may not be quite as bright as the prospects for tungsten.

“There is a lot more molybdenum available in the world,” Lawrence said.

That means that in the grand scheme of things, extracting molybdenum from Iron Mountain will likely be a long-term bet for Sultan.

In the short term, the company hopes to have enough funds available soon to continue drilling for both molybdenum and tungsten in the next few weeks.

Meanwhile, the strength of global zinc pricing will prompt Lawrence to pore over historical exploration data, as he attempts to come up with potential drilling targets on a property that has produced 7.9 million tonnes of lead-zinc ore grading 1.8% lead and 3.8% zinc.

“It could be that we start with the zinc first,” he said, adding that any new mining infrastructure would have to be capable of processing both zinc and tungsten.

At an age when most of his colleagues are retired, Lawrence seems revitalized by the task of trying to get the mine he once managed back into production.

“For me, this is a very interesting project beca

use I worked here for twelve years,” he said.

During the site visit, he was right at home strolling through the underground workings of a mine that was once a pioneer of trackless mining methods.

Using a handheld light, he had no trouble picking out the grains of scheelite that glow under ultraviolet fluorescent rays on the drift walls of the old Dodger mine.

Lawrence thinks the biggest challenge may be finding jackleg miners to do the underground drilling work once production resumes.

“We may have to train them on site,” he said.

Be the first to comment on "Sultan Dusts Off Jersey Emerald"