SITE VISIT

Sudbury, Ont. — For many years, the mines around Sudbury were a settled story: two big companies, one big intrusion that hosted all the big deposits, one standard theory on their origins, one city that lived on nickel. The role of junior exploration companies — if they had a role at all — was to find mineralization and option it to the majors.

Now the two big companies are components of two even bigger companies, and — at least at the level of mining, if not processing — the old duopoly has been broken by the arrival, and then flourishing, of mid-tier nickel miner FNX Mining (FNX-T, FNXMF-O). And with Xstrata (XSRAF-O, XTA-L) chopping down the old Falconbridge exploration portfolio to concentrate on its best projects, and the downsizing of the Inco land package at the beginning of the decade, junior companies have a much freer hand to make their way in the camp.

So metaphorically, for sure, and often physically as well, Wallbridge Mining (WM-T, WLBMF-O) is walking over ground that hasn’t been trod for a long time in its search for base and precious metal deposits in the North Range of the Sudbury structure and in the footwall rocks farther out. The North Range, historically, is where the action wasn’t; the early Sudbury mines were on the South Range, and development on the North Range, notably in the Levack area, took place later. But that was always an access and proximity issue, rather than a question of prospectiveness; the North Range geology is, on the gross scale, a mirror image of the south.

Out beyond the North Range are the offset dykes, intrusions that look, in the field, like the Nipissing or Matachewan dykes that break up much of northern Ontario. But they are made of Sudbury magma, and though they have only rarely contributed to the camp’s mineral inventory — except for the large Copper Cliff dyke — they are especially interesting exploration targets for a junior.

“If your mandate is nickel, you’re not going to be looking outside the Sudbury Intrusive Complex, very far,” says Bruce Jago, Wallbridge’s vice-president of exploration.

That thinking — we have mills to feed — kept the majors near the main intrusive ring itself, with specific targets in mind. A junior, on the other hand, can be more flexible about commodities, and can consider the offset dykes, which often host copper and platinum group elements, as primary exploration targets.

Moreover, the footwall rocks to the north of the intrusive complex may enclose rocks from the main intrusion, tectonically or magmatically emplaced as the main structure collapsed and compressive movement, mainly oriented northwest-southeast, forced the ring together. That provides a model for grassroots exploration through the whole area northwest of the Sudbury structure.

Wallbridge has set itself up as the serious junior explorer in Sudbury, partly by amassing the camp’s third-largest land holding and partly by assembling a workforce with intimate experience of the area. (And also, you could add, by cashing up to do real exploration work.)

Its most obvious success is the Broken Hammer deposit, on its Wisner property about 20 km north of the city. Wallbridge has a small inferred resource there — 251,000 tonnes grading 1% copper, 0.1% nickel with 1.6 grams platinum, 1.6 grams palladium and 0.6 gram gold per tonne. But a small resource, near surface in an established camp, is worth an economic look, and a preliminary economic analysis of the deposit is under way.

Metallurgical testing on the Broken Hammer material showed 92% of copper, 89% of platinum and 78% of palladium are recoverable. The initial analysis looked at production of 325 tonnes per day from a small pit, but consultants have recommended a higher mining rate.

The start would be a bulk sample from a ramp to confirm the resource grades. Much of the platinum occurs as coarse grains of the platinum sulphide sperrylite, which makes for difficult sampling. A bulk sample, by testing a larger volume of material, would provide a better estimate of the grade (and typically, in these cases, the bulk grade proves to be higher than the one estimated from drilling).

The Wisner property, which contains Broken Hammer, was one of the Falconbridge properties that didn’t make the major’s cut some years ago; Wallbridge now controls the property and Xstrata holds a 1.5% net smelter return. Another Xstrata joint-venture property is Frost Lake, where Wallbridge and Xstrata — equal partners, with Wallbridge managing the work — have a $1.4-million program to do 4,800 metres of drilling.

Frost Lake, on the east side of the Sudbury structure, north of Capreol, is the type case of Sudbury intrusive rocks finding their way into the country rock outside the basin. The style of mineralization is low on copper and nickel sulphides, but can be very high in platinum-group metals. “It makes it hard to look for ’em,” says geologist Joshua Bailey, “but at the same time that could be where the opportunity lies.”

Drilling at Frost Lake in 2006 turned up a 16-metre intersection that graded 0.48% nickel and 0.27% copper, with platinum group credits. Immediately to the south, along the strike of the intrusive contact, a joint venture of Lonmin (LNMIF-O, LMI-L) and Companhia Vale do Rio Doce (RIO-N) is drilling the Capre 3000 zone. Four of the CVRD Inco drill holes cut long intervals with modest copper and nickel grades, but very high precious metals: a 98-metre intersection ran 0.49% copper and 0.1% nickel, with 2 grams per tonne in combined platinum, palladium and gold, and a 42-metre intersection ran 1.78% copper, 0.2% nickel, and 3.3 grams combined precious metals.

Wallbridge’s drilling at Frost Lake, now under way, will be guided by a Titan-24 geophysical survey, combining induced polarization and magnetotellurics; the system, which can “see” deeper mineralization than other induced-polarization systems, provided more drill targets on the property.

Frost Lake also undercuts the one-size-fits-all magmatic model of the genesis of the Sudbury nickel deposits. The intrusive rocks are plenty hot — “it actually melts the country rock,” says Bailey — but there is abundant evidence of hydrothermal alteration in the mineralized rocks, sodium feldspar where the temperature is higher, and epidote where it is lower.

Jago says fluid inclusion studies on the mineralization may develop indicators to discriminate mineralized from unmineralized rock. At this stage, they know hotter temperatures and more saline fluids are better, and have confirmed platinum-group elements and metal chlorides in the fluid inclusions. The inclusions show formation temperatures between 450C and 580C.

While hydrothermal processes are clear enough at Frost Lake, Broken Hammer appears to be somewhere near the transition between magmatic and hydrothermal processes, while mineralization at Trill Lake, on the western end of the Sudbury complex, shows evidence of tectonic “squeezing” of sulphides into the country rock. Targets on Trill are to be drilled in the fall, based on Titan-24 results.

Lonmin is the 50% partner at Trill, as it is on three other properties: Foy, on the North Range, where soil geochemistry and surface prospecting has turned up copper and platinum group showings; Skynner, a short distance north of Frost Lake; and Creighton South, near CVRD Inco’s Creighton mine on the South Range. The platinum miner can earn a 65% interest in any of the properties by funding a feasibility study and production on it.

Lonmin took down a 10.8-million-share placement of Wallbridge shares in June, at 60 per unit, providing just under $6.5 million to Wallbridge’s treasury. Lonmin got 5.4 million warrants in the placement, which it can exercise for $1.00 each, a buy that would give it an 18% interest in the company. The deal gives Lonmin a right to enter a joint venture on Wallbridge’s North Range properties and a 5-year right of first refusal on the other Sudbury-area properties, subject to the existing agreements with

other partners.

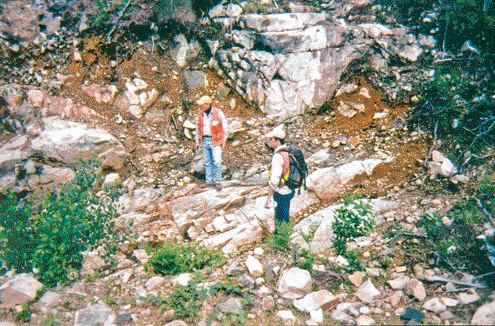

With majors concentrating on near-mine exploration, opportunities have moved down the food chain in Sudbury, and some sideways geological thinking has shown there are plenty of targets to look at. “It’s amazing in a hundred-year-old camp,” says Bailey, “that you can still find things on the surface.” Or is it?

Be the first to comment on "Wallbridge finding Sudbury mineralization beyond the basin"